Valerie Johnson has watched—and fought against—political attacks on academic freedom for years. A political scientist and associate provost of diversity, equity and inclusion at the Catholic DePaul University, Johnson understands well the political incentives for conservatives to bring universities to heel.

This year brought an avalanche of new and continuing attacks on what professors can teach, speak about and research at American colleges and universities, led by the Trump administration and exacerbated in states like Florida and Texas, where Johnson describes these changes as swift and effective.

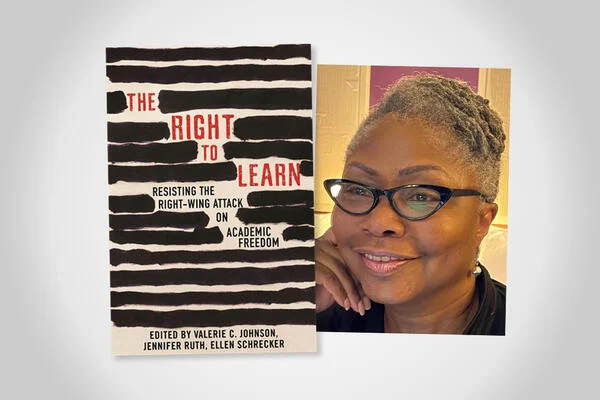

Together with co-authors and editors Jennifer Ruth, a film professor at Portland State University, and Ellen Schrecker, a professor emerita of American history at Yeshiva University, Johnson wrote The Right to Learn: Resisting the Right-Wing Attack on Academic Freedom (Beacon Press, 2024). In October, the book was granted the American Association of Colleges and Universities’ Frederic W. Ness Book Award, an annual honor that highlights the “book that best illuminates the goals and practices of a contemporary liberal education.”

Johnson spoke with Inside Higher Ed over Zoom about the impetus for the book and how she interprets the escalating attack on academic freedom today.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What prompted you to write this book? Was there a specific moment when the scope of this campaign against academic freedom that you describe became unmistakable for you?

A: Yes, it was the summer of 2021. A friend of mine was working with the African American Policy Forum, and they wanted to sound the alert that we were seeing a rollback of rights. And so they had asked Jennifer Ruth, my co-author and co-editor of the book, to work on what they called the Faculty Senate campaign. Twenty twenty was a momentous year. We began to see gag orders about what could be taught. So Jennifer and I … wanted to alert all faculty senates across the United States that we were seeing this erosion of academic freedom and that they should pay attention. We asked them to write resolutions asking their administrations to reaffirm academic freedom.

Q: How have faculty senates or governing bodies adapted—or failed to adapt—to the current legislative landscape?

A: Well, I would like to say I’ve seen quite a bit of resistance, but unfortunately people have a way of conceding when their livelihoods are at stake. And how you answer that question is also determined by where you are in the country. If you’re in a red state—like Florida, like Texas—where there are prohibitions like, “Hey, you cannot teach on this, this, this and this,” then either you stay there and withstand some degree of punishment, or you leave. A lot of faculty are leaving red states for bluer states.

It’s actually been very surprising to me. This period in American history has really caused me to rethink what I originally believed about human nature. It is very surprising how cowardly people are … I am a political scientist by training, and I [know] only about 4 to 5 percent of people will protest anything. And we have seen various rallies, protests, etc., but it hasn’t been as engaging as I would like to see.

Q: One of the things that the book addresses is that efforts on the right to degrade academic freedom are strategic rather than reactive. What evidence convinced you that this was an organized, long-term project?

A: There’s always been attempts to erase history. Frederick Douglass said a long time ago that America is false to its past. It’s false to its present, and it resigns itself to be false to the future.

America has always created a story that it is something it is not, and I think the values that we have are largely aspirational. When universities talk about their mission statements, they’re not saying it’s [complete], they are saying, “This is who we’d like to be.” There has always been a concerted effort to blame the victim when it comes to people who have marginalized identities and to ensure that, largely, their stories are not told. And so through education, if you could limit discussions of race and social equality, then people aren’t thinking about it. They’re not thinking about passing legislation that pursues those goals. And you could make people believe that, “Hey, all the problems of the past have been resolved,” when, in fact, if you look empirically, they haven’t.

Q: When you were doing your research, were there any state-level policies or actors that really surprised you, either in their influence or how quickly they spread?

A: Yeah, I would say Florida and Texas. It was very quick. [Governor Ron] DeSantis definitely took over the university system very quickly [with] Don’t Say Gay and Anti-Woke. I mean, it’s amazing, but it’s an easy setup. For the average citizen, it’s a part of the culture wars where they see LGBTQIA rights, for example, or women’s rights, and they’re alarmed by them … It is “me against them,” and particularly in red states and the Bible Belt, it has been a pretty easy sell to the citizenry because it aligns with some of their well-cherished values, but it doesn’t promote human rights. It doesn’t promote a country or a world where people are seen not by any sort of cultural or identity markers, but by their membership in the human race.

Q: Are there any aspects of the current debate that you think are most misunderstood, either by the media or the public or folks in higher ed?

A: Yes, I think there are a couple of things that are really misunderstood. One is structural inequality, or when you look at, for example, inequality by race. I think most people think that the civil rights movement resolved any social economic inequality when, in fact, it did not. I always use the metaphor of a Monopoly game gone wrong—just because you change the policy doesn’t mean you change the conditions. So let’s say you and I are playing a game of Monopoly, and halfway through the game, I realize you’ve been cheating all along. So I call you out on it, and your response to that is, “OK, let’s change the policy. No more cheating.” And then you say, “Let’s resume the game.” The problem with that is you have already amassed the red hotels, the green houses. Generation by generation, those people who benefited from slavery or land appropriation of the Native Americans and Mexicans, or Jim Crow and residential segregation, that’s a cumulative advantage. For those people who were disadvantaged, there’s a cumulative disadvantage that moves forward from generation to generation. Existing racial inequality—I don’t think people actually understand it. They saw shows like The Cosby Show, and they are like, “Oh, wow, all people from minoritized backgrounds, they’ve made it.” In fact, it’s really a myth.

To that extent, if you say that you want to provide opportunities that create inclusion on college campuses, they’re looking at that like, “Well, wait a minute. They’ve made it. So this is unfair to me.” Then you have this disdain for DEI. Of course, for people between the ages of zero and 18 in America, the majority of them are nonwhite. So every single year, campus enrollment is becoming less white … and American universities and colleges that are going to have to depend on American students for their enrollment will increasingly have to court and recruit students who are nonwhite because of the demographic shift.

Q: How should universities communicate with the public about academic freedom without reinforcing the right wing framing that expertise equals elitism?

A: One thing that is constantly on my mind is: How do you talk about something as heavy as academic freedom? In a way, I wish we would have retitled the book something like “The Right to Learn: Resisting the Attack on What You Can Learn,” or something like that. When you put “academic freedom,” people ask, what is academic freedom? People know about free speech, but people don’t know about academic freedom. That is why you have an increasing number of students who come to college campuses believing that they should get a tailor-made curriculum.

So, what can universities do? I believe in community education. I love it when community groups and politicians ask me to come and speak to regular community folk. We have to see our enterprise as not only teaching in the university, but outside of the university, and that could be done with op-ed pieces or just going where people are—churches, community institutions … I think that’s the only way it’s going to happen. We have to get out of the ivory tower.