Art and Research Communication

The Public Health Resonance Project at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa collaborated with a talented artist to create illustrations to better share their research. Have you incorporated art into your research communications?

The Public Health Resonance Project at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa “amplifies unique attributes and deep connections across regionally and culturally relevant physical activities for health promotion and community wellness, locally and globally.”

Art and illustration can enhance how you share your research. Collaboration between the Public Health Resonance Project and a talented artist included feedback from the whole team to ensure the illustrations were culturally relevant to the research. “It was necessary.”

This episode features

- Dr. Tetine Sentell, co-lead of the Project and Chin Sik & Hyun Sook Chung Endowed Chair in Public Health Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi Mānoa

- Esme Yokooji, a graduate student in Public Health and social media coordinator for the Project

- Sunnu Rebecca Choi, an award-winning illustrator, printmaker, and artist

The episode on Art and Design to Share Your Research Story felt so special. It’s the 1st time these collaborators have all come together on video 🎧🎙️✨

I love that I got to design their website and bring us together for this conversation. We talk about the research, art, and share 3 beautiful new illustrations with you.

There’s many ways to be more visual with your research such as data visualization, illustration, comics, science art, photography, video. I love that the PH Resonance Project found an artistic partner in Sunnu Rebecca Choi.

I hope this video inspires you. Save this post for later. You may not have 32m 5s to watch or listen today. But save it even if you just have a hint of ‘I want art for my research’ and you’re unsure how you’ll get there.

A dream I have is that more research groups, labs, and centers invest in collaborating with talented artists like Rebecca. These partnerships can help people around the world engage with (and share) research that’s meaningful to them. And also I love art.

Omg if this post (or the video) inspires you to reach out to an artist about working together? Please share it with me, I would love that! 🥹

Behind-the-scenes

Before we dive into the interview, I have a quick story to share with you about recording. Or, you can skip right to the interview.

My computer crashed right in the middle of our recording 💻😱

I’m freaking out. My desktop computer light is blinking red at me like a danger sign. When I try to cycle the computer on the fan goes crazy.

The podcast episode going live today? There was a moment there I thought it wasn’t gonna happen. When I finally made it back on, maybe 10 minutes later, I was delighted to find my guest happily chatting away. When I went back to watch the recording, they were so cute. “Oops! Looks like our host has dropped off,” and then right back to their conversation about art and research.

We were able to complete our recording. But this episode needed a bit more.

We had high resolution art to share. There was a story in there that needed attention to bring out 🎨✨️

And thank goodness I sought help. I soon learned my own audio/video? Parts of my solo video were unusable. Super lagged.

Luckily, I have a talented husband I’ve been teaming up with for his professor dad’s art focused YouTube channel. I love that Matthew can help.

The video is finally ready for you. Thank you!

Technical problems may happen 💯

Have you worried about something going wrong with your computer too? Things may go wrong with tech, but I hope it doesn’t for you! 🫶

Every time something goes wrong, I get anxious about my own unsurity of what comes next. People are often kind and understanding. When I’m the one experiencing technical issues, it feels like a huge deal and inconvenience to people. I have to remind myself: When I’m on the other side of that? I always understand. It’s super relatable. I can’t envision myself getting mad, angry, or hurt but someone else’s technical glitch. If your computer crashes in the middle of our meeting, I’ll totally get it too.

I wanted to share this story with you because for a moment there? It felt like this podcast episode may not happen. But it did. We made it happen. I’m so happy / relieved. I’m proud to share it with you 👋😄

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer on building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

Interview

The special 2024 logo was designed by Sunnu Rebecca Choi.

Tetine: Rebecca, we love you so much. I’m so excited to meet you in real life.

Rebecca: Thank you. I was really looking forward to meet you guys, all.

Tetine: You’re like our artistic hero, so it’s so fun to have an opportunity to do this. Thank you, Jennifer for making it happen.

Jennifer: Wait, Tetine. How did you first find Rebecca? How did you first connect?

Tetine: Oh yeah, so I have it in my slides.

Jennifer: Oh, you do? Okay. Show me your slides.

Yeah, yeah yeah! As a team, this is kind of our first time all meeting live and I’m so excited that we’re all here together. Tetine, why don’t you start us off. Would you please introduce yourself and tell people a little bit about your research?

Tetine: Sure. Aloha. I’m Tetine Sentell. I’m a Professor here at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa in Public Health. I’m the department chair of public health and I am one of the co-founders of the Public Health Resonance Project, which is a really exciting, interdisciplinary, collaborative synthesis of literature, engagement with literature, dissemination of literature project we’ve been doing now for several years that this team has assembled as part of, and I’m just been so grateful to be part of that. And it’s really about sharing opportunities for strength-based public health promotion, especially around culturally and regionally relevant physical activity and how that’s meaningful to people as individuals, as families, as communities, and as collectives.

Jennifer: What are some examples of those culturally relevant activities? Just so people have an idea.

Tetine: So in Hawaiʻi, some examples would be hula, spearfishing, outrigger canoe paddling, for instance. And then of course, in many other places there are resonance and activities from culturally relevant dance, folk dances, regional relevant dances, practices in the water, practices in the land.

Jennifer: Esme, would you introduce yourself?

Esme: Sure. My name is Esme Yokooji. I’m a Master’s of Public Health student at UH Mānoa, and I am the graduate research assistant on this project. I’m in the NHIH or Native Hawaiian and Indigenous Health specialty at UH. And, in my free time, I am someone who participates in these activities. I do Okinawan dance. I like to volunteer in ʻĀina doing things like Kalo planting and just conservation and restoration work in our natural habitats here in Hawaiʻi. That’s what initially drew me to this project is just the real life connection and seeing how community engages with these things. So mahalo for having us.

Jennifer: Rebecca, you are coming here from London. This is fun. London, Hawaiʻi, and I’m in San Diego. Rebecca, tell me a little about your journey as an artist.

Rebecca: Hi, my name is Sunnu Rebecca Choi. I’m an illustrator and printmaker based in London, but I’m originally from South Korea, lived in Canada and United States and now ended up in London somehow. And then I used to be a fashion designer in New York and Toronto, but then I decided to change my career, become an illustrator. Right now I’m specializing in editorial illustration as well as children’s book illustration, mostly focusing editorial illustration wise, mostly focusing on medical scientific as well as psychologies. And I work with a lot of different university magazines as well.

Jennifer: Thank you. So everyone listening knows, I did design the website [for the Public Health Resonance Project]. I had so much fun doing this project because there are so many visual elements to all of those activities and to the people who are engaging with them. This is about people.

Tetine: I am so happy to be here because we’ve been working on this international, collaborative project for so many years, and one of the things we really wanted to do was make it so beautiful and really make it so it could be disseminated and shared in ways that inspire and engage and delight people. And so I developed this logo as we began consolidating and thinking about disseminating in collaboration with some partners, and in particular with my husband and all who helped build it. So thank you, Craig. It was a meaningful logo. We felt it was really important. I have this slide here to really show we were inspired by the Hawaiian colors and the deep ocean from the shore to the sunset, and really thinking about the levels of influence and the social ecological model, which is our theoretical influence in the background from a public health perspective and thinking about the ripple effects and the waves that grow and build and move across. And really thinking about the place to connect the project and the connections and the links, the ripples, the reflections.

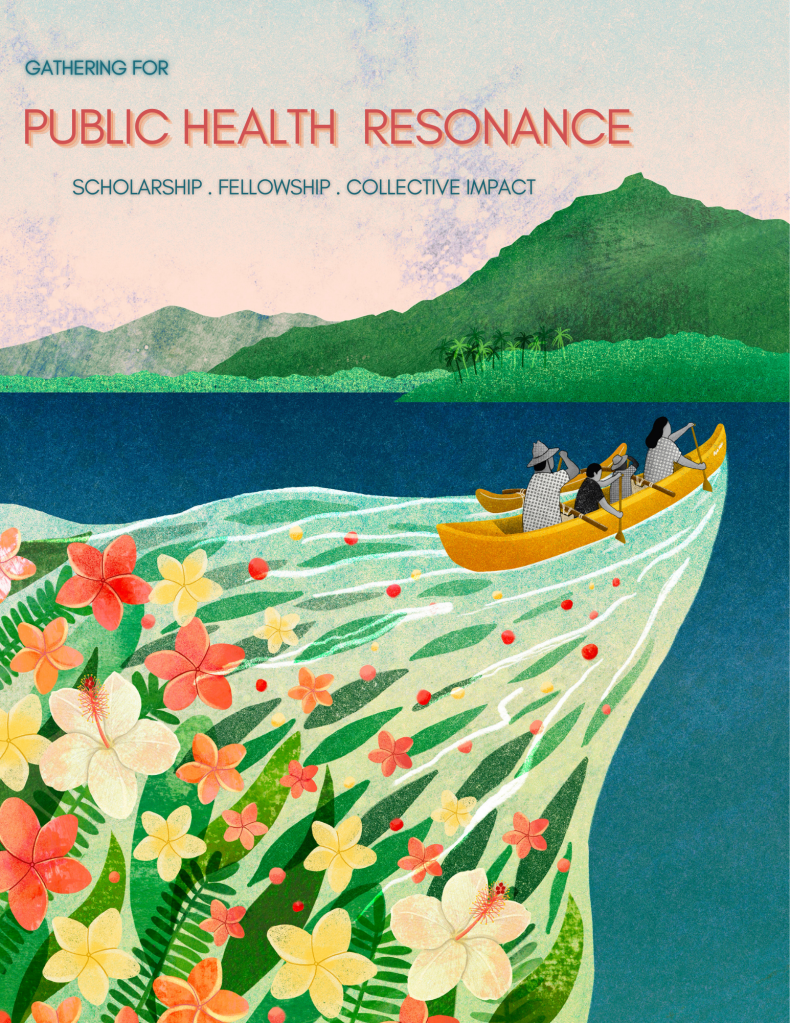

We had this endowed chair and this opportunity, and so I was really reflecting and thinking about this and this absolutely beautiful art came in my alumni magazine. Can you see how beautiful that is? It’s so pretty. I even have the one I pulled out of my alumni magazine and it was Rebecca’s artwork and it was so beautiful and it really had the feeling of what we were thinking about of these reflections, of these perspectives. You can see it has a lot of depth and story to the artwork as well as just being so peaceful and beautiful and meaningful. And so that’s how I found the artwork and had no idea how to engage with artwork or what to do in this particular way if it was contractable through a university through our funds. But anyway, just cold emailed through the link in the website and she has a beautiful website if you’ve seen it. And through that started a conversation that has just been really so fruitful and so exciting and just I’m so honored to be part of this. And in collaboration also with Esme and others who’ve really helped support and build the artwork into spaces that we can use it for all the things we wanted to do.

Jennifer: That is amazing. I’m so happy that we had a chance to hear that kind of origin story because I feel like there’s so many possibilities that we just don’t know exist as researchers, as academics, even as artists. What can we do to better connect and help shape our ideas together? Rebecca, how did you feel when Tetine first reached out? Is this a kind of project that you’ve done in the past?

Rebecca: No, actually it was really interesting because I haven’t really worked with other universities before. So was it, what university?

Tetine: Middlebury.

Rebecca: Yeah, Middlebury Magazine. That was my first alumni magazine that I worked with, university. And then when Tetine emailed me I was like, “Oh, I actually didn’t know it was released already.” That’s how I knew that magazine has been issued. Yeah, so that was really interesting. And then since then I’ve been working with a lot of universities in United States, so that opened a new opportunity for me as well.

Jennifer: And so I’m curious Tetine, what about art helps bring the community together? Why invest in this kind of visual element?

Tetine: Of course, art inspires us, engages us, pulls us in, makes us think, is important to us as humans, as people in the world. But I also think in academia we do a lot of intricate, thoughtful, engaged practices and activities that often are not accessible because they’re deep inside words and publications, sometimes even behind paywalls. And I think there is a lot of intricacy and story in even peer-reviewed academic journal papers, much less the smaller summaries of them. View open access resources from the PH Resonance Project.

And so it just felt like this was such an opportunity relative to the work, work now, to disseminate and to share it, to think about how it’s helpful, how it’s good for mental health, how it’s engaging, how it’s good for physical health, how it’s good for strength. All that was sort of built in the background of how to share out, this was so important to disseminate in communities and to people. And then with that joy, right. This is a strength-based activity. It’s a thing that brings people together, makes them happy, makes them joyful, connect with each other. And I think that’s one of the things art can do. It felt like such a nice synergy and such an amazing opportunity to really tie all those things together.

Jennifer: You brought up joy, and that’s something that I really get not just from the beautiful illustrations that have been customized to represent different activities that the project is researching, but also in the new version of the logo, in the thoughtfulness of how it all comes together through, you have created brochures, event flyers, like physical things and materials to help people engage in person. And that artwork also creates that same warmth and feeling online. Rebecca, I’m curious about your process working on what feels like something really representative of community. What was that process like for creating the artwork for this project?

Rebecca: The process-wise, whenever I receive a brief, I start with the research. Understanding how each activity is carried out, what equipment is used, and learning about the cultural context, from coding to landscapes. And that process helped me make the imagery as accurate and respectful as possible. Also, every time I create the illustration, my goal was to highlight public health at the community level, showcasing people coming together, whether it’s a mother and a child, a family, or a wider community group. I wanted the artwork to capture the moment and that sense of connection and shared care. I believe illustration has the power to bring people closer and help them resonate more deeply with the subject matter. And I think that was my main goal in creating those illustrations. Usually, when I’m working on the brief, I come up with three different concepts or ideas for each illustration.

Whenever, if I’m working on the canoe activity, I come up with three different composition or concept or focusing on something different for each illustration for the client to choose from. And that’s how I start creating the art. And then once we decide which concept we are going to go with and then I go render the illustration, my rendering process is quite interesting because I’m a printmaker as well. I create all the textures using printmaking techniques, either monoprinting, etching, or any kind of things that I can get hands on and I scan them in. And then in terms of the final illustration, I use Procreate on iPad and then bring all the textures together on iPad. So it’s a mix of digital and analog process.

Tetine: That’s why it’s so tactile. It’s like you can really feel it even through the internet. It’s really beautiful that way.

Esme: I felt the same way though. When I first saw the illustrations, I was like, “Oh, it’s almost like it’s painted on washi paper.” Like watercolor on washi. It’s so beautiful.

Rebecca: I will sometimes use the watercolor and washi or, accurate. So in my studio I have bunch of papers with all different kinds of textures and colors, which I can just use on any kind of illustration.

Esme: That’s so cool.

Tetine: It is. It’s so beautiful. I just love how it all works together and it really has such a feeling about it. Your work is so specifically you, but then you’re also using it so collaboratively to share other people’s vision, which is not an easy thing to do, I think as an artist, and I really appreciate the collaborativeness with which you’ve approached this, these. The first one as the initial one, as thinking about how to share and showcase what we were trying to do. And then very specifically in a regional context and an actual, it’s a specific way, it’s a specific bay you’re coming into and the landscape like you mentioned, and the practice and the movement and the arms, and then really thinking about who is in the canoe and what they’re wearing. And then as we have thought about it for the other resonating activities, to be willing and offer the opportunity for us to really be in collaborative conversation, even as the artwork is pretty far along to be like, “Oh no, we’ve gotten comments from our community members that this isn’t correct or we need to fix this.” I’m just so grateful for that.

Rebecca: Yeah, it was really, really interesting learning process for me as well because I knew about, briefly know about samba or Tongan, but I didn’t really specifically know about their clothing or how it works and how the body moves, things like that. So for me, it was a really, really good opportunity to learn about different activities as well.

Tetine: And I think that’s actually, exactly the project. In the sense that each one has not only resonance across, but these unique, very specific pieces of engagement, the land with the ocean with movements particular, with stories and songs and clothing from the community and care. And so the opportunity to showcase that and to showcase that very specifically about, in place for people doing it with each other as families and as communities, not specifically as, not as a show, but as a practice in community. And that has been really important. And as we share and tell the story of the artwork, that’s a really important piece of the, of our sharing of what you’ve been doing as well. Aloha.

Esme: I also want to say, Rebecca. I used to work in Heʻeia at the fish pond that kind of portrays that bay. And it was so funny because when we had the first kind of in-person activity, it actually took place in Heʻeia, but in the back of the valley. And it was so wonderful because when we showed the work to the people that are participating, they’re like, “Oh, that’s, Heʻeia, that’s here. They were able to instantly recognize from the art. And I think that, even people that weren’t affiliated with the project, were interested and curious. And I think the art was a big draw, seeing a place, recognizing it, feeling properly represented. So I just wanted to say thank you for that. That was so wonderful.

Rebecca: Yeah, also thank you for all the feedback that Tetine gives. Also, all our illustrations were reviewed by experts and that’s how we can actually get a correct imagery and then representative of the place as well.

Tetine: Yeah, and I’ll just say the funders of this, the endowed chair that I hold that has allowed this opportunity, it’s from a family enterprise and it’s all been in the background. I mentioned my husband helping with this. There’s a lot of family connections because Mele [Look], my beloved colleague who has done this project with me, certainly has helped connect to some of the cultural and regional experts, but in particular on the Heʻeia ridgeline, her husband Scott is a geologist, and he was like, “This ridge line is not correct. You have to go down. It happens like this, not like that.” And he drew a line for the ridge line so it was proper. That’s the level of detail and actually cultural consultation and regional consultation that’s been possible through this collaborative project.

Jennifer: It sounds like a lot of people were involved in the art making, and that’s something that’s probably really unexpected for folks who are listening to this. So it was the two of you as well as it sounds like experts?

Tetine: Yeah, yeah yeah. As Rebecca mentioned, we had the brief, we have a conversation, and then she would send three sort of options of things. And then those three options we would run by people who practice those activities, who work in the region, who engage in the practice. That certainly included my colleague Mele, who’s been part of this all along in every way, but also, exactly, people who paddle for the paddling one, people who participate in wild skating for the ones you’ll see in a minute we’ll talk about, and people who do samba, people who do Tongan dance. And so exactly this. So out of the three that we’ve chosen one to go with, and that one is really prioritized. Community, that it’s about being with family or being with others to do practices that bring people joy together, collaboratively in their real lives. That this is about, sometimes they are ceremonies at a wedding or at a party with a community, but they’re not about a show. They’re about a practice together in community.

And so that’s always been the background of the activities we’ve been showcasing. But then from those and from the one we’ve chosen, then she does a more developed artwork. And then from that more developed artwork, that’s where we really are like, okay, well this color or this clothes or this line or this is not how the arm would be, or this is not the exact proper direction of the canoe relative to the shoreline. That level of detail has been really important and part of the iterative conversation. And then we go back to consult and come back. So it’s a very iterative process.

Jennifer: When you started the project, did you know how long it would take to produce art using all of this feedback?

Tetine: For me, that is kind of how the process of most of the work that I do works, where there’s a lot of, we work a lot with community and in practice and public health is about that. I would say for me, not a surprise, but I did feel really bad for Rebecca. I felt it was a lot to ask the artist to engage in sort of the academic consultation process at that level of detail. But she was a really good sport about it.

Rebecca: It was very interesting because I also, I do longer projects or shorter projects. Usually the book projects are very long. Sometimes it lasts from three months minimum to one year or more than one year. But then editorial projects usually ends within two weeks. I think this project was in between, I guess.

Jennifer: I appreciate that. And for folks who are listening, if you’re considering working with an artist asking about their timeline, but also considering who you need to bring into the conversation for that art is helpful upfront so that you can talk about it together.

Tetine: Could I just add to that exact thing, which is that because of this project being so specific about culture and place and about those practices, it was vital and we couldn’t have done it otherwise. Because if the artwork for the practice doesn’t make sense to the people participating, we shouldn’t do that artwork at all, right? And so that was built into this. I could imagine other scenarios where you wouldn’t need quite such level of detail because maybe you’d be talking about just a feeling or something to connect with this, but this was so vital that we have that level of detail

Jennifer: Esme, as someone who is using the art to create flyers and other kinds of, I would say marketing materials, but is it marketing materials?

Esme: Well, I would say my background is also in organizing, and that was where I had most of my social media, video editing experiences actually in making, for lack of a better word, propaganda. But kind of trying to inculcate people and inform them, somewhat a combination of educational materials. And I think the goal of this project is, Tetine spoke on, is just to shine a light and a spotlight on these different activities, on these different researchers, on the work that they’re doing and its value. I think for me, what I’ve really enjoyed about being a part of this team is how much Tetine specifically stresses the importance of cultural competence and humility. And I think that understanding how specific everything is, understanding how tailored it is, really conceptualizing who our audience is, who’s going to be benefited by our materials, is something that’s really important to me, specifically being in Native Hawaiian and Indigenous Health. Because I think having more culturally tailored interventions or even having more culturally tailored messaging, having artwork that is accurate that people can recognize, that immediately draws them in I think is really valuable and important. It’s been truly really fun, honestly, to make materials and just experiment with the different kinds of things, whether it’s making a video intro or editing a logo for a flyer or collaborating on a poster or any manner of things. It’s been a joy.

Jennifer: Tetine, what would you like folks to know about, okay, there’s so many people out there who are like, “I do want a website. I do want to have beautiful artwork for my events. I do want these things, but I don’t know if it’s worth my time as the PI [Principal Investigator].” You are the decision maker here. And so I’m curious, what made you know that this was worth it for you in terms of your energy?

Tetine: Yeah, I mean, I think it is a conundrum of academic practice these days actually. This how we engage in the PR of the work we do in a sort of dissemination campaign. Generally, people do so much valuable work that they don’t [promote] because of their own demands of academia. They don’t have the time, capacity, support system to help be sharing that out. I guess I would advocate not for this to be something that individuals need to do only because it isn’t something an individual can do only. I was able to pull this together by the amazing collaboration, by being fortunate to have, hold this endowed chair and being senior enough in my own career that the publication process or grant making process was not the only thing I really needed to prioritize relative to my own goals of my academic, what I wanted to do with my career.

And so it has been actually a joy and an honor to be part of this collaboration, to keep building it, to keep growing it, to engage in sharing it out. Like as Esme is saying and dissemination materials might be one of the terms I might want to use for some of the things we’re doing to think about how we’re sharing out and why. What we want to do is think about how to build in the opportunity for innovative ways in which we showcase the work we do in academia and in art being one of the fundamental ways in which we can share out. And then the art being collateral, like Esme is mentioning and we’ve talked about. And that, Jennifer, is one of the great skills that you hold is how we share out the beautiful work that an artist achieves in collaboration with us, like Rebecca is doing. Then in YouTube and LinkedIn, or in community, and handouts and flyers. How do we do that? That’s certainly not something we learn in graduate school, but in the background is all this important work that deserves to be showcased.

Jennifer: Ah, wonderful. Are there slides that you did not share that you want to be sure to get into the video? Is there anything else that we should be sure to talk about today?

Esme: Only that I think from what I’ve experienced, because a lot of what I do specifically focuses on Indigenous Health and what did this Project was specifically trying to reach and elevate and focus on communities that have historically been marginalized, experienced disparity. But coming from the perspective of how is culture a source of strength, how is connectivity to land and to heritage a source of strength? And I think that using art is something that reinforces that message because a lot of times Indigenous Arts and Traditions, whether it’s storytelling or even hula, is considered an art form as well as a physical activity has been marginalized. So using art as a means to tell these stories and amplify these messages feels so right and is a source of resonance for me anyway. And engaging in this work.

Rebecca: So much of this project, the process was about discovery for me as well. Through this collaboration, I learned so much about the diverse cultural backgrounds behind each brief. And also me as a Korean Canadian based in London, I have so much different cultural diversity within me as well. So it was really valuable experience for me to work on those illustrations and artistically it also encouraged me to explore new colors and compositions that I never used before as well. So finding ways to express not just the activities itself, but the joy and vitality that shines through them while highlighting the connection between people, community and nature, was really, really enjoyable working on this brief.

Jennifer: Well, I’m very excited for the art to come. I’ve never had such beautiful art packaged, ready for me to consider for a website design. I felt really honored to be able to work with the thoughtfulness that I could tell everyone who was involved with this project put into the creation of these art pieces. And there’s new ones that I guess they’re maybe going to be premiered on this video if they’re not on the website first, and I’m very excited to share them with all of you. So Tetine, let’s do your slides.

Tetine: This was the beautiful artwork we talked about before that I was inspired by. And then this is exactly like, to showcase both the artwork itself and then the artwork, the initial one we’ve been talking about so much, the one, the paddling, the outrigger canoe paddling one, you can see the family, you can see Heʻeia in the background. And then you can also see how we used the artwork as a piece of the story we were telling, which was that we were doing various gatherings over the world, essentially, last year. And that we were thinking about, this was something, we had note cards, we had a poster, we had small business card size handouts to really share and tell the story about what we were doing. So the new artwork includes resonances specifically with this one. This is based in Hawaiʻi and our community here. And then we wanted to really think about how this resonated in other places.

So this is wild skating in Scandinavian lands. And we had feedback, for instance, specifically here in this one about the trees that actually from our Swedish colleagues said no one would ever go out without a helmet. And so we put a helmet on the child because we were like, that makes sense. That’s the cultural practice. Same with the backpack and the way she’s holding her poles. That the backpack, they were like, we’d never go out into the wilderness without some sort of backpack or something to be safe. So again, really thinking about how communities engage in these practices in real life versus what you might see on a tourist brochure. That was really important to us. Again, you can see the mom and her child. And then really, dance is a really important culturally and regionally relevant community, relevant practice, again, all over the world.

And so dance, a lot of the research is in dance specifically for so many different pieces of staving off dementia, Parkinson’s, community wellness, mental health. And so here we have our Tongan dance example we talked about earlier, and the samba dance example with input, in collaboration from colleagues from Tonga and Brazil, specifically talking about what this might look like in practice and what this might be like. And so for instance, in the samba one, at first we had these very elaborate headdresses and activities and our colleagues said, well, certainly we do that in Carnival and something, but that’s not what you would see in a community. That’s a special event for a different type of piece. And so if you want to think about how people would do these practices in real life, in community, it would be more casual like this. And same, we talked a lot about in the Tongan example about the clothes, what that might look like, how people would be engaged, what would be respectful, what would be expected, that this is a bit of a dressy event, but also a family event and what that might look like and how the arms are, the stories being told with the hands and the arms and the motions and what music would be relevant.

You can see in the background a lot of those conversations. The last thing I just wanted to highlight is, as we talked about earlier, we have different logos to go with each one. Because the resonance is across, and the first one really started with the Hawaiian sunset and colors. And then you can see these colors in the background are from some of these other places as well. So highlighting that resonance across that, we really want to think about the colors and the schemes, in terms of people’s communities and specific places. Which is to share, we really talked about this, and I know I think Jennifer, you have an example, but just how we’ve been able to engage in our own activities and practices using this artwork because of Esme’s skillset as well. And because of the capacities and the conversations, including with you, Jennifer, and the website. How to share out and showcase the conversations we’ve had with so many wonderful experts across the globe. And this really is just such a tremendously collaborative project. And so that’s really been a great joy of this project as well, is how to all the strengths and experiences and skillsets that people bring to the table together, really thinking about where we showcase that and how to do that in the most beautiful, respectful, exciting, engaging way possible.

Jennifer: Yay. Thank you so much for recording this with me. I feel like you were all so excited to talk that it really is going to make for an engaging episode for people, and I really hope that it inspires other folks to consider collaborating with an artist or even reaching out to Rebecca because you’re such a valuable resource for people. I love how much attention that you give to not just what needs to be communicated, but who it’s communicating with and who needs to be involved in the process. It’s just beautiful. Thank you all for being here today. Yeah. Anything else before we wrap up?

Tetine: No, but thank you, Jennifer. You’re a great visual communicator also, and I’m just really grateful for all the expertise you’ve brought to the story of the Public Health Resonance Project and the capacity to share it out as well. Those are skillsets I didn’t have and didn’t have access to either, and really have been grateful for that as well. Just thank you and again, for bringing us all together for this great opportunity. This is a great joy. It’s been a great joy to meet and a great joy to meet Rebecca, to have Esme here, who’s just been a joy as well. And Jennifer, thank you for all that you do for us as well. You also are a great joy!

Esme: Thank you so much.

Jennifer: Yay!

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer on building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

A special thank you to my husband, Dr. Matthew M. Pincus, for his editing and storytelling support with this episode. If you need help with a video, reach out to him at [email protected]