Student journalists have their fingerprints on more than 282 public radio or television stations across the country, providing behind-the-scenes support, working as on-screen talent or reporting in their local communities for broadcast content. But over $1 billion in federal budget cuts could reduce their opportunities for work-based learning, mentorship and paid internships.

About 13 percent of the 319 NPR or PBS affiliates analyzed in a report from the Center for Community News at the University of Vermont operate similarly to teaching hospitals in that a core goal of the organization is to train college students. Nearly 60 percent of the stations “provide intensive, regular and ongoing opportunities for college students” to intern or engage with the station.

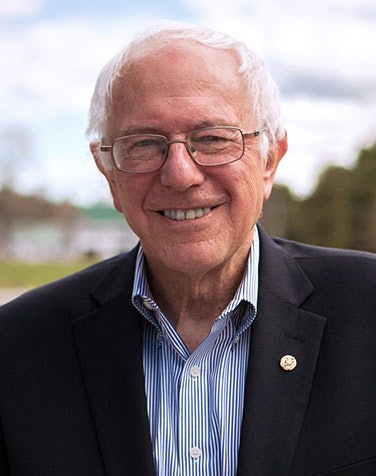

Scott Finn, news adviser and instructor at the Center for Community News and author of the report, worries that the cuts to public media and higher education more broadly could hinder experiential learning for college students, prompting a need for additional investment or new forms of partnerships between the two groups.

In July, Congress rescinded $1.1 billion in federal funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which funds public media stations including NPR and PBS. The cuts threaten the financial stability of many stations, some of which are directly affiliated with colleges and universities.

Working at a public media station provides a variety of benefits for students, Finn said. In his courses, Finn partners with community outlets that will publish students’ stories, depending on the quality and content, which he says motivates students to submit better work.

“Being published, being broadcast is important. The whole focus of the exercise changes,” Finn said. “It’s not just trying to please me as the instructor or a tick box for a grade. They have real-world consequences. Their story will have an impact. It will move people, it will change policy, and that knowledge them inspires them to work harder.”

Most students want internship opportunities; a recent study by Strada found students rate paid internships as the most valuable experience for improving their standing as a candidate for future jobs. But nationally, there’s a shortage of available, high-quality internships compared to the number of students interested in participating, according to a 2024 report from the Business–Higher Education Forum.

A Handshake survey from earlier this year found 12 percent of students in the survey didn’t have an internship before finishing their degree, largely because they lacked the time or weren’t selected for one.

For interns or students working directly in the studio, partnering alongside career journalists also gives them access to a professional network and a career field they may not otherwise engage in.

But student journalists aren’t the only ones who lose out when internship programs are cut.

Emily Reddy serves as news director at WPSU, a PBS/NPR member station in central Pennsylvania associated with Penn State University. Reddy hosts a handful of student reporting interns throughout the calendar year, training them to write, record and broadcast stories relevant to the community.

“[Interns] bring an energy to the newsroom,” Reddy shared. “They’re enthusiastic. They are excited to go out to some board meeting that no one else wants to go to. They bring us stories that we wouldn’t know about otherwise.”

WPSU uses a variety of funding sources to pay student interns, including endowed scholarships at the university and donated funds. But like many other stations, WPSU is facing its own cuts. Earlier this year, Penn State reduced funding to the station by $800,000, or around 9 percent of the station’s total budget. That resulted in a cut of $400,000 from CPB.

In response, WPSU shrank its full-time head count, laying off five staff members and cutting hours for three. Roles vacated by retirements were left unfilled. In October, the station will lose around $1.3 million as a result of the federal cuts, though Reddy doesn’t know what the full impact will be on staffing.

WPSU had planned to increase its internship offerings, and Reddy is still hopeful that will happen. However, the laid-off personnel were among those responsible for managing learners.

“The big thing that I’m concerned about working with students is that you can’t just have the students; somebody has to train them, somebody has to edit them, somebody has to voice coach them and clean up their productions,” Reddy said.

About 12 percent of the stations in the Center for Community News’s report don’t sponsor interns, and they pointed to budget cuts as a key reason why. For stations experiencing financial pressures, Finn hopes newsrooms find creative ways to keep students involved in creating stories, including classroom partnerships or faculty editors who trim and refine stories. Universities are uniquely positioned to assist in this work, Finn said, because they have more resources than public stations and have a strong motivation to place students in successful internship programs.

“This is a really important time for universities to double down on their relationship with public media stations and not walk away from it,” Finn said. “A lot of [stations] are these underutilized resources, in terms of student engagement and student learning.”

Finn also says alumni and other supporters of student learning and public media can help to fill in gaps in funding, whether that’s supporting a paid full-time faculty role to serve as a liaison between students and stations or to endow internship dollars.

“If public media stations are important to student success, then university advancement has to embrace the public media station as a part of its mission and help raise money for it,” Finn said.