Dive Brief:

- The University of North Carolina System will treat class syllabi as public records effective Jan. 15 and require instructors to post their syllabi to a “readily searchable” online platform beginning in the 2026-27 academic year.

- Under the Friday policy change, each syllabus will have to include a course’s name, description, methodology for student assessment and required course materials, as well as a “statement noting that the course engages diverse scholarly perspectives to develop critical thinking, analysis, and debate and inclusion of a reading does not imply endorsement.” The list does not include the instructor’s name or contact information.

- The change, adopted during UNC’s winter break, comes as the system has been inundated with public records requests for course materials, with different universities coming to opposite decisions about whether to fulfill them.

Dive Insight:

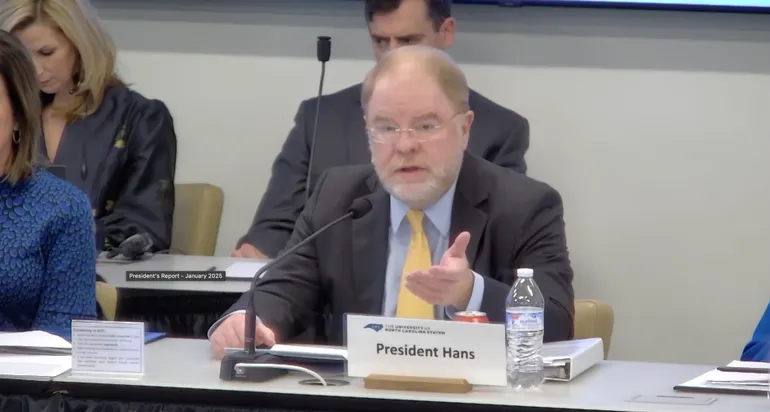

Friday’s policy change carried out UNC President Peter Hans’ promise earlier this month that the 16-college system would soon adopt “a consistent rule on syllabi transparency.”

He publicly announced the forthcoming change in a Dec. 11 op-ed for The News & Observer after multiple UNC campuses received enormous public information requests this year from at least one conservative organization.

In July, the Oversight Project, a conservative activist group that spun off from The Heritage Foundation, submitted a massive request to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, seeking course materials for over 70 undergraduate and graduate classes, ranging from topics on business to urban planning to nursing to African American studies.

Course titles included “United States Latino/a Theatre,” “Gender and Sexuality in Islam” and “Diversity and Inequality in Cities.” From those classes, the group requested “all syllabuses, lecture slides, course materials, or presentation materials presented to students” that include terms such as “sexuality,” “diversity and inclusion,” “implicit bias” and “cultural humility.”

UNC-Chapel Hill declined to fulfill the request in August, on the grounds that it would infringe on instructors’ intellectual property.

An hour away, however, administrators at the UNC Greensboro ordered faculty to submit spring 2025 syllabi to fulfill a similar records request, according to WUNC, the public radio station operated by the university.

Hans said this month that a single, campus-wide rule would “ensure that everyone is on the same page and similarly committed heading into each new semester.” He argued that public syllabi would enable students to make informed academic decisions and allow UNC to “stand behind our work” amid “an age of dangerously low trust in some of society’s most important institutions.”

But Hans‘ edict prompted swift backlash from faculty.

Two professors at UNC Charlotte — Caitlin Schroering and Annelise Mennicke — protested the forthcoming change in an op-ed published by NC Newsline the same day.

“Publicly posting required course content and course objectives can lead to the weaponization of this information,” the pair said. “This will produce a chilling effect where faculty feel pressure to self-censor the content of their courses to avoid being pulled into the political spotlight.”

Schroering and Mennicke also raised concerns that publicly posting syllabi “in an era of political extremism” could risk the safety of those on UNC campuses, citing the wave of disrupted lectures, faculty doxxings and politically motivated shootings.

“Publicly posting course syllabi only increases access to sensitive information by bad actors. This is a real security concern that can be avoided,” they said.

In his op-ed, Hans acknowledged that the policy change would open campus up to critique “in a time when healthy discussion too often descends into outright harassment.”

“There is no question that making course syllabi publicly available will mean hearing feedback and criticism from people who may disagree with what’s being taught or how it’s being presented,” he said. “That’s a normal fact of life at a public institution, and we should expect a vibrant and open society to have debates that extend beyond the walls of campus.”

But he ultimately argued that the benefits outweighed the costs.

“We will do everything we can to safeguard faculty and staff who may be subject to threats or intimidation simply for doing their jobs,” Hans wrote.

The North Carolina conference of the American Association of University Professors also pushed back on the change. The group urged Hans to ditch the policy in a petition that garnered over 2,800 signatures as of Monday afternoon.

“If your concern is to guide students along their academic journey, then ask that syllabi be accessible only to students,” the letter said. “Faculty want what is best for their students and go to great lengths to make sure they have what they need, but do not want people who are not in their classes accessing their syllabi.”

But making syllabi available publicly, the petition said, instead appears to be a “politically motivated” move with “no evidence of any accrued benefits for students, nor of goodwill being generated between the university and the public.”

“Instead, providing public access to syllabi during a period of heightened partisanship and rising political violence looks like partisan pandering with a cost to faculty and no benefit,” it said.