We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74’s republishing terms.

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74’s republishing terms.

Key points:

Between kindergarten and second grade, much of the school day is dedicated to helping our youngest students master phonics, syllabication, and letter-sound correspondence–the essential building blocks to lifelong learning.

Unfortunately, this foundational reading instruction has been stamped with an arbitrary expiration date. Students who miss that critical learning window, including our English Language Learners (ELL), children with learning disabilities, and those who find reading comprehension challenging, are pushed forward through middle and high school without the tools they need. In the race to catch up to classmates, they struggle academically, emotionally, and in extreme cases, eventually disengage or drop out.

Thirteen-year-old Alma, for instance, was still learning the English language during those first three years of school. She grappled with literacy for years, watching her peers breeze through assignments while she stumbled over basic decoding. However, by participating in a phonetics-first foundational literacy program in sixth grade, she is now reading at grade level.

“I am more comfortable when I read,” she shared. “And can I speak more fluently.”

Alma’s words represent a transformation that American education typically says is impossible after second grade–that every child can become a successful reader if given a second chance.

Lifting up the learners left behind

At Southwestern Jefferson County Consolidated School in Hanover, Ind., I teach middle-school students like Alma who are learning English as their second language. Many spent their formative school years building oral language proficiency and, as a result, lost out on systematic instruction grounded in English phonics patterns.

These bright and ambitious students lack basic foundational skills, but are expected to keep up with their classmates. To help ELL students access the same rigorous content as their peers while simultaneously building the decoding skills they missed, we had to give them a do-over without dragging them a step back.

Last year, we introduced our students to Readable English, a research-backed phonetic system that makes English decoding visible and teachable at any age. The platform embeds foundational language instruction into grade-level content, including the textbooks, novels, and worksheets all students are using, but with phonetic scaffolding that makes decoding explicit and systematic.

To help my students unlock the code behind complicated English language rules, we centered our classroom intervention on three core components:

The impact on our students’ reading proficiency has been immediate and measurable, creating a cognitive energy shift from decoding to comprehension. Eleven-year-old Rodrigo, who has been in the U.S. for only two years, reports he’s “better at my other classes now” and is seeing boosts in his science, social studies, and math grades.

Taking a new step on a nationwide level

The middle-school reading crisis in the U.S. is devastating for our students. One-third of eighth-graders failed to hit the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) benchmark in reading, the largest percentage ever. In addition, students who fail to build literacy skills exhibit lower levels of achievement and are more likely to drop out of school.

The state of Indiana has recognized the crisis and, this fall, launched a new reading initiative for middle-school students. While this effort is a celebrated first step, every school needs the right tools to make intervention a success, especially for our ELL students.

Educators can no longer expect students to access grade-level content without giving them grade-level decoding skills. Middle-school students need foundational literacy instruction that respects their age, cognitive development, and dignity. Revisiting primary-grade phonics curriculum isn’t the right answer–educators must empower kids with phonetic scaffolding embedded in the same content their classmates are learning.

To help all students excel and embrace a love of reading, it’s time to reject the idea that literacy instruction expires in second grade. Instead, all of us can provide every child, at any age, the chance to become a successful lifelong reader who finds joy in the written word.

The need for literacy experts is especially pronounced in charter schools, 70% of which had no librarian in 2020-21, according to the joint report. Of smaller schools with under 200 students, nearly two-thirds lacked librarians, as did about a third of high-poverty schools, the report noted.

Although Guadalupe Centers Middle School lacks a library, in the wake of the school’s recently implemented Aztecs Read initiative, students in 6-8 grades in 2022-23 averaged 3.67 points of Rasch UnIT — or RIT — growth on the NWEA reading assessment, which accelerated to an average of 6.17 RIT points in 2024-25, the school reported.

With about 370 students, Guadalupe Centers aims to serve as a hub for Kansas City’s Hispanic community, said Christopher Leavens, teacher and lead for English/language arts, who led the establishment of Aztecs Read as an initiative to put a library in every classroom along with various related initiatives such as author visits and an online reading log. A multipurpose room had served as a library—but without a staff librarian, possibly for the school’s entire history.

“I’m an English teacher, and I believe so much in students being able to have good literature, and stories that speak to their culture,” said Leavens, who’s been teaching for 14 years and is in his fourth year at Guadalupe Centers. “Independent reading is so valuable in developing their reading and writing, and in developing who they are, as people — communications skills, empathy, connection. I felt it was important for me to build that up.”

The initiative began during Leavens’ first year at the school, solely in his 7th grade classroom. But toward the end of the school year, he decided that the entire school, which has a total of nine classrooms devoted to students in various places along the English-language journey, should have a dedicated classroom library, and his colleagues, school leaders and the district stepped up to help. For those in the early stages of English language development, the books are in Spanish, but as they advance along the continuum, they move to English-language reading.

“We built it out over time,” he said. “Beyond getting books in the kids’ hands, we’ve tried to build up a reading culture. … Our district has been incredibly supportive of us, financially, to invest in the classroom libraries and build it out.”

Beyond the classroom libraries, Aztecs Read has hosted author visits — including with Pedro Martín, who wrote the graphic memoir “Mexikid.”

“He was able to come in, give a presentation, sign books and have lunch with our kids,” Leavens said.

The program has also invested in the online reading log Beanstack, which enables students to track their reading progress. “It can provide more infrastructure, accountability and build out reading to the home and get parents involved,” he said.

That tracking capability led to “Book of the Break” challenges, during which the school provides different tiers of incentives for students to read over school breaks for at least 10 minutes every day, Leavens said. Those who do enter a drawing for the grand prize, a pair of headphones; or the second prize, one of 10 gift cards to AMC Theatres, which were donated after a teacher reached out to the company.

At the very least, students — who typically wear uniforms — get to enjoy a dress-down day, he said.

“Not all kids are in homes where they have books, or reading role models,” Leavens said. “Getting kids to read is not always easy to do. … The team we have, too, is so resourceful and hard-working. We still have a lot of work to do, but we’ve been able to build up the amount these kids are reading for fun, and their enjoyment when they have read.”

This article is part of Bright Spots, a series highlighting schools where every child learns to read, no matter their zip code. Explore the Bright Spots map to find out which schools are beating the odds in terms of literacy versus poverty rates.

This story is part of The 74’s special coverage marking the 65th anniversary of the Los Angeles Unified School District. Read all our stories here.

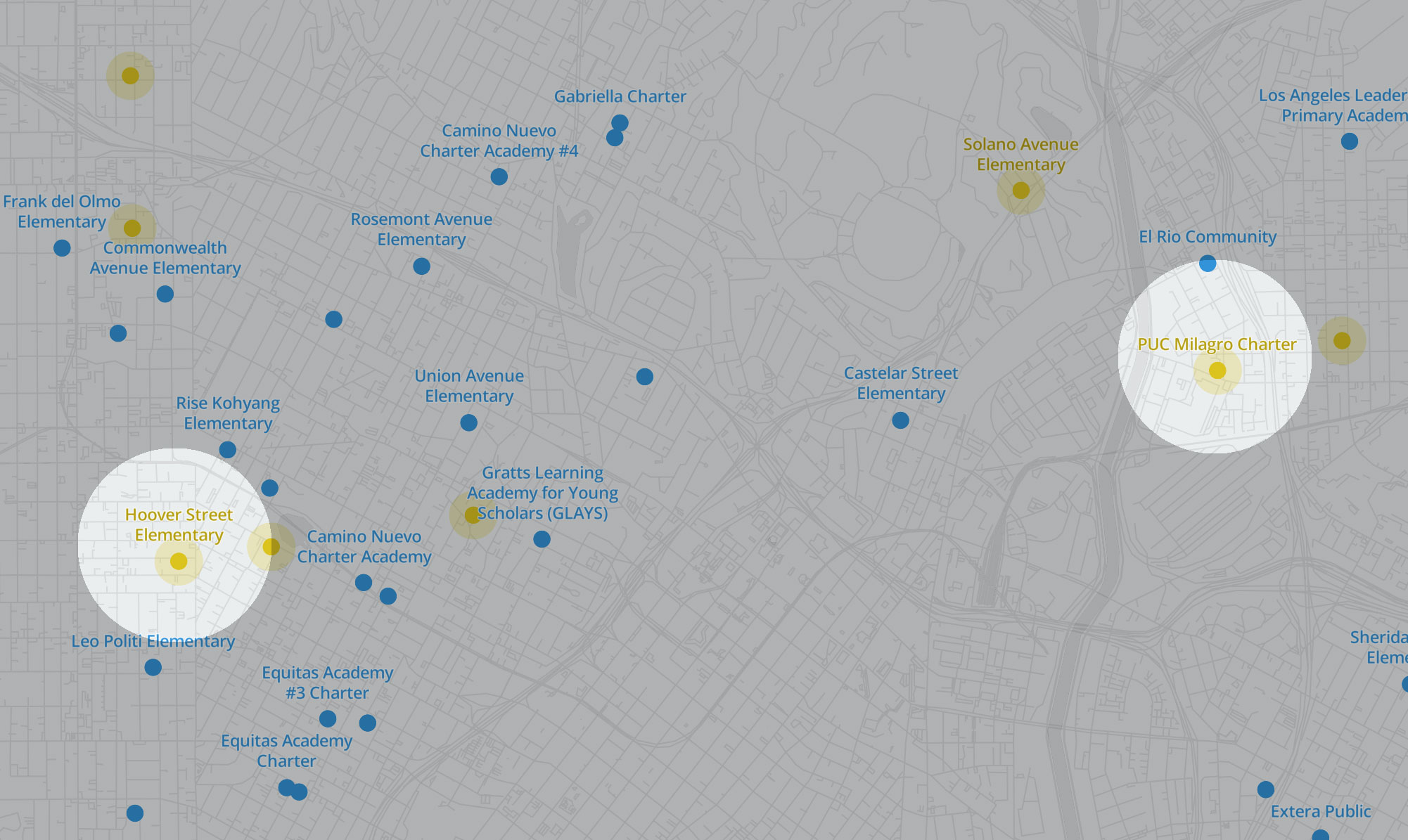

When The 74 started looking for schools that were doing a good job teaching kids to read, we began with the data. We crunched the numbers for nearly 42,000 schools across all 50 states and Washington, D.C. and identified 2,158 that were beating the odds by significantly outperforming what would be expected given their student demographics.

Seeing all that data was interesting. But they were just numbers in a spreadsheet until we decided to map out the results. And that geographic analysis revealed some surprising findings.

For example, we found that, based on our metrics, two of the three highest-performing schools in California happened to be less than 5 miles apart from each other in Los Angeles.

The PUC Milagro Charter School came out No. 1 in the state of California. With 91% of its students in poverty, our calculations projected it would have a third grade reading rate of 27%. Instead, 92% of its students scored proficient or above. Despite serving a high-poverty student population, the school’s literacy scores were practically off the charts.

PUC Milagro is a charter school, and charters tended to do well in our rankings. Nationally, they made up 7% of all schools in our sample but 11% of those that we identified as exceptional.

But some district schools are also beating the odds. Just miles away from PUC Milagro is our No. 3-rated school in California, Hoover Street Elementary. It is a traditional public school run by the Los Angeles Unified School District. With 92% of its students qualifying for free- or reduced-price lunch, our calculations suggest that only 23% of its third graders would likely be proficient in reading. Instead, its actual score was 78%.

For this project, we used data from 2024, and Hoover Street didn’t do quite as well in 2025. (Milagro continued to perform admirably.)

Still, as Linda Jacobson reported last month, the district as a whole has been making impressive gains in reading and math over the last few years. In 2025, it reported its highest-ever performance on California’s state test. Moreover, those gains were broadly shared across the district’s most challenging, high-poverty schools.

Our data showed that the district as a whole slightly overperformed expectations, based purely on the economic challenges of its students. We also found that, while Los Angeles is a large, high-poverty school district, it had a disproportionately large share of what we identified as the state’s “bright spot” schools. L.A. accounted for 8% of all California schools in our sample but 16% of those that are the most exceptional.

All told, we found 45 L.A. district schools that were beating the odds and helping low-income students read proficiently. Some of these were selective magnet schools, but many were not.

Some of the schools on the map may not meet most people’s definition of a good school, let alone a great one. For example, at Stanford Avenue Elementary, 47% of its third graders scored proficient in reading in 2024. That may not sound like very many, but 97% of its students are low-income, and yet it still managed to outperform the rest of the state by 4 percentage points. (It did even a bit better in 2025.)

Schools like Stanford Avenue Elementary don’t have the highest scores in California. On the surface, they don’t look like they’re doing anything special. But that’s why it’s important for analyses like ours to consider a school’s demographics. High-poverty elementary schools that are doing a good job of helping their students learn to read deserve to be celebrated for their results.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how

By now, the memo from the attorney general’s office outlining the administration’s interpretation of civil rights laws as they apply to higher education has made the rounds.

It took me back to my grad school days. I took a seminar in literary theory—the ’90s were a different time—and remember being struck particularly by reader-response theory. As I understood it, it argued that the meaning of a text is determined by the reader rather than the writer. Meanings aren’t as random as that might make it sound; “interpretive communities” take shape around a host of sociological, as well as personal, variables. In other words, we learn how to interpret texts partially by modeling on how people around us do. The same text can be read differently depending on your social location.

I’ve had personal experience of that in rewatching beloved movies or rereading beloved books from my teen years. In high school, Revenge of the Nerds struck me as funny and refreshing. As an adult, I can’t get past its sexism. The movie hasn’t changed, but I have.

The assumptions that different interpretive communities make aren’t always conscious. They don’t work like geometric proofs. In my experience, the most frustrating conflicts happen when different unconscious assumptions (or givens) crash into each other. Having to defend something you take as obviously true feels like either a complete dismissal or a slap in the face; it quickly moves discussion from reasoned disagreement to exasperated incomprehension. (“How can you possibly say that?”)

If you don’t recognize when those assumptions clash, it’s easy to get stuck in cycles of verbal shadowboxing. Is someone arguing against single-payer health insurance because they believe that a regulated market system would be more efficient? If so, a reasoned discussion may be worthwhile. Or are they arguing against it because they believe that poor people deserve to die? In that case, arguments around relative efficiency are pointless. Some folks are skilled at disingenuously using reasonable-sounding arguments to defend horrific assumptions; the tip-off is when they switch from one argument to a contradictory one as soon as they start to lose. The sooner you detect that move, the more time and emotional energy you can save.

The AG’s memo offers a glimpse into the unconscious (or at least unspoken) assumptions animating the administration.

Take, for instance, the assertion that “geographic or institutional targeting” is a proxy for discrimination. The only way that can make sense is if you assume the colleges and universities they had in mind are private ones that draw students from around the country. In the case of community colleges, most have a geographic boundary in their name and/or a defined service district. Monroe Community College, in Rochester, N.Y., is defined by its location in Monroe County. It gives a discount—economists call that price discrimination—to residents of its county. Students from out of county pay more.

And that’s not unique to MCC; it’s the way most community colleges work. Even those that don’t have out-of-county or out-of-district price premiums usually have out-of-state premiums. The same is true of most public universities. I’ve personally had the experience of paying out-of-state tuition for two kids at public universities; it’s not fun. Is that illegal now? If so, I’ll apply for a refund from the Universities of Virginia and Maryland, posthaste.

Of course, the vast majority of colleges and universities draw overwhelmingly from their own state. That’s a direct version of geographic targeting. A national higher ed policy based on the presumption that geographic targeting is the problem simply ignores the vast majority of the sector.

The issues are also more granular than that. The memo ignores scholarships offered by donors for graduates of particular high schools. Are those illegal now? Private donors frequently favor graduates of their own high schools, or people from the towns in which they grew up. Do we have to turn those donors away now? Or only if the towns in which they grew up are too diverse? Are sports scholarships only OK if they don’t draw too diverse a group of students? If so, then sailing is fine and basketball is suspect. Hmm. I think there’s a word for that.

I imagine the answer the attorney general would offer would be something like “as long as geographic preferences aren’t about increasing diversity, they’re OK.” But that presumes a lot. For example, New York City is more diverse than, well, just about anywhere; if a struggling small college on Long Island starts recruiting aggressively in New York City, is that about diversity or about enrollment? And how do you know?

Discerning institutional intent isn’t straightforward. Mixed motives are entirely normal. For example, is the movement to improve graduation rates meant to help students, budgets or institutions’ public images? The answer is all of the above. Is making colleges more inclusive of people of different backgrounds for the benefit of the newly included, the folks already there or institutional budgets? Again, yes.

A serious discussion would look less at intentions and more at incentives. If decades of public disinvestment force public institutions to behave more like private ones, basing more of their budgets on tuition, then we shouldn’t be surprised to see them compete for students. They’ll do what they have to do. If we want colleges to stop competing for students, we should insulate them from the economic need to do so. It has been done before.

The universe assumed in the memo tells us a lot about the people behind it. It presumes a world in which economic issues don’t matter, intentions are obvious, people have only one motive at a time and elite institutions constitute the entire industry. It reflects the kid who thought Revenge of the Nerds was a breath of fresh air. But that kid eventually grew up and learned that there was more to the world than was dreamt of in his philosophy. The word for that process is education.

Benjamin Herold’s Disillusioned: Five Families and the Unraveling of America’s Suburbs offers a rare and urgent account of how postwar suburbia—often seen as the apex of the American Dream—has become a fractured and unstable landscape, especially when it comes to public education. Through the personal stories of five families across the US, Herold builds a layered portrait of promise and betrayal.

This is a book educators and students should read—not for comfort, but for clarity.

Rutgers professor Kevin Clay (L) interviews Benjamin Herold (R), July 2025

Herold’s central thesis is as unsettling as it is undeniable: the post-WWII suburban boom was not a neutral act of growth, but a racialized, exclusionary economic project that served some families at the expense of others. Communities that were once predominantly white and upwardly mobile—like Compton and Penn Hills—are now struggling with declining school enrollment, shrinking tax bases, and rising segregation by income and race. In places like Evanston and Atlanta, attempts to reckon with inequality are often met with community resistance, bureaucratic inertia, and political backlash. Meanwhile, rapidly diversifying suburbs around Dallas reflect the shifting demographics of the country—and the urgency of crafting a new educational and civic infrastructure that doesn’t fall into the same traps.

Herold doesn’t flatten these places into statistics. Instead, he follows five families trying to raise their children in what were once considered “good” school districts. Some are Black families confronting the limits of inclusion. Others are white families grappling with their own privilege and discomfort. Through them, we see how suburban schools continue to promise opportunity while too often delivering disappointment—especially for children of color, immigrant families, and those living paycheck to paycheck.

Educators reading Disillusioned will recognize the impossible pressures placed on schools: to close racial achievement gaps, maintain property values, please demanding parents, and adapt to political mandates—often without adequate funding or community cohesion. Herold shows how schools, even with the best intentions, are asked to solve problems they did not create and are not empowered to fix on their own.

This book is especially useful for those who teach about inequality, education policy, or American history. It connects housing policy, school funding, and institutional trust in ways that are personal and accessible. For students, it opens up a broader view of how structural forces—redlining, white flight, suburban sprawl, and tax policy—shape their daily lives and futures, often invisibly.

Disillusioned also serves as a sobering reflection for anyone involved in reform efforts. School choice, desegregation programs, testing regimes, anti-racism initiatives—all have had mixed results, in part because they fail to challenge the core structures of suburban exclusion. Without deeper shifts in housing, taxation, and civic engagement, educational equity remains aspirational.

Herold’s reporting does not offer easy solutions. But it does offer something more valuable: context, empathy, and a sense of urgency. He shows us that while the suburbs may look different than they did in 1950, many of the underlying rules remain the same—and the consequences are growing more severe.

The five towns Herold explores are not outliers. They are bellwethers. The racial and economic tensions playing out in Compton, Evanston, Penn Hills, Atlanta, and Dallas are already shaping the future of America’s suburbs—and its public education system. These are not just stories about local politics or school board fights. They are about the future of democracy, the erosion of public goods, and whether the next generation will inherit anything better.

For anyone serious about education, equity, or the American future, Disillusioned is essential reading. It demands not just understanding, but action.

Sources

Herold, Benjamin. Disillusioned: Five Families and the Unraveling of America’s Suburbs. The New Press, 2024.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright, 2017.

Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press, 1985.

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership. University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Five years after the pandemic forced children into remote instruction, two-thirds of U.S. fourth graders still cannot read at grade level. Reading scores lag 2 percentage points below 2022 levels and 4 percentage points below 2019 levels.

This data from the 2024 report of National Assessment of Educational Progress, a state-based ranking sometimes called “America’s report card,” has concerned educators scrambling to boost reading skills.

Many school districts have adopted an evidence-based literacy curriculum called the “science of reading” that features phonics as a critical component.

Phonics strategies begin by teaching children to recognize letters and make their corresponding sounds. Then they advance to manipulating and blending first-letter sounds to read and write simple, consonant-vowel-consonant words – such as combining “b” or “c” with “-at” to make “bat” and “cat.” Eventually, students learn to merge more complex word families and to read them in short stories to improve fluency and comprehension.

Proponents of the curriculum celebrate its grounding in brain science, and the science of reading has been credited with helping Louisiana students outperform their pre-pandemic reading scores last year.

In practice, Louisiana used a variety of science of reading approaches beyond phonics. That’s because different students have different learning needs, for a variety of reasons.

Yet as a scholar of reading and language who has studied literacy in diverse student populations, I see many schools across the U.S. placing a heavy emphasis on the phonics components of the science of reading.

If schools want across-the-board gains in reading achievement, using one reading curriculum to teach every child isn’t the best way. Teachers need the flexibility and autonomy to use various, developmentally appropriate literacy strategies as needed.

Phonics programs often require memorizing word families in word lists. This works well for some children: Research shows that “decoding” strategies such as phonics can support low-achieving readers and learners with dyslexia.

However, some students may struggle with explicit phonics instruction, particularly the growing population of neurodivergent learners with autism spectrum disorder or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. These students learn and interact differently than their mainstream peers in school and in society. And they tend to have different strengths and challenges when it comes to word recognition, reading fluency and comprehension.

This was the case with my own child. He had been a proficient reader from an early age, but struggles emerged when his school adopted a phonics program to balance out its regular curriculum, a flexible literature-based curriculum called Daily 5 that prioritizes reading fluency and comprehension.

I worked with his first grade teacher to mitigate these challenges. But I realized that his real reading proficiency would likely not have been detected if the school had taught almost exclusively phonics-based reading lessons.

Another weakness of phonics, in my experience, is that it teaches reading in a way that is disconnected from authentic reading experiences. Phonics often directs children to identify short vowel sounds in word lists, rather than encounter them in colorful stories. Evidence shows that exposing children to fun, interesting literature promotes deep comprehension.

To support different learning styles, educators can teach reading in multiple ways. This is called balanced literacy, and for decades it was a mainstay in teacher preparation and in classrooms.

Balanced literacy prompts children to learn words encountered in authentic literature during guided, teacher-led read-alouds – versus learning how to decode words in word lists. Teachers use multiple strategies to promote reading acquisition, such as blending the letter sounds in words to support “decoding” while reading.

Another balanced literacy strategy that teachers can apply in phonics-based strategies while reading aloud is called “rhyming word recognition.” The rhyming word strategy is especially effective with stories whose rhymes contribute to the deeper meaning of the story, such as Marc Brown’s “Arthur in a Pickle.”

After reading, teachers may have learners arrange letter cards to form words, then tap the letter cards while saying and blending each sound to form the word. Similar phonics strategies include tracing and writing letters to form words that were encountered during reading.

There is no one right way to teach literacy in a developmentally appropriate, balanced literacy framework. There are as many ways as there are students.

The push for the phonics-based component of the science of reading is a response to the discrediting of the Lucy Calkins Reading Project, a balanced literacy approach that uses what’s called “cueing” to teach young readers. Teachers “cue” students to recognize words with corresponding pictures and promote guessing unfamiliar words while reading based on context clues.

A 2024 class action lawsuit filed by Massachusetts families claimed that this faulty curriculum and another cueing-based approach called Fountas & Pinnell had failed readers for four decades, in part because they neglect scientifically backed phonics instruction.

But this allegation overlooks evidence that the Calkins curriculum worked for children who were taught basic reading skills at home. And a 2021 study in Georgia found modest student achievement gains of 2% in English Language Arts test scores among fourth graders taught with the Lucy Calkins method.

Nor is the method unscientific. Using picture cues with corresponding words is supported by the predictable language theory of literacy.

This approach is evident in Eric Carle’s popular children’s books. Stories such as the “Very Hungry Caterpillar” and “Brown Bear, Brown Bear What do you See?” have vibrant illustrations of animals and colors that correspond with the text. The pictures support children in learning whole words and repetitive phrases, suchg as, “But he was still hungry.”

The intention here is for learners to acquire words in the context of engaging literature. But critics of Calkins contend that “cueing” during reading is a guessing game. They say readers are not learning the fundamentals necessary to identify sounds and word families on their way to decoding entire words and sentences.

As a result, schools across the country are replacing traditional learn-to-read activities tied to balanced literacy approaches with the science of reading. Since its inception in 2013, the phonics-based curriculum has been adopted by 40 states and the Disctrict of Columbia.

The most scientific way to teach reading, in my opinion, is by not applying the same rigid rules to every child. The best instruction meets students where they are, not where they should be.

Here are five evidence-based tips to promote reading for all readers that combine phonics, balanced literacy and other methods.

1. Maintain the home-school connection. When schools send kids home with developmentally appropriate books and strategies, it encourages parents to practice reading at home with their kids and develop their oral reading fluency. Ideally, reading materials include features that support a diversity of learning strategies, including text, pictures with corresponding words and predictable language.

2. Embrace all reading. Academic texts aren’t the only kind of reading parents and teachers should encourage. Children who see menus, magazines and other print materials at home also acquire new literacy skills.

3. Make phonics fun. Phonics instruction can teach kids to decode words, but the content is not particularly memorable. I encourage teachers to teach phonics on words that are embedded in stories and texts that children absolutely love.

4. Pick a series. High-quality children’s literature promotes early literacy achievement. Texts that become increasingly more complex as readers advance, such as the “Arthur” step-into-reading series, are especially helpful in developing reading comprehension. As readers progress through more complex picture books, caregivers and teachers should read aloud the “Arthur” novels until children can read them independently. Additional popular series that grow with readers include “Otis,” “Olivia,” “Fancy Nancy” and “Berenstain Bears.”

5. Tutoring works. Some readers will struggle despite teachers’ and parents’ best efforts. In these cases, intensive, high-impact tutoring can help. Sending students to one session a week of at least 30 minutes is well documented to help readers who’ve fallen behind catch up to their peers. Many nonprofit organizations, community centers and colleges offer high-impact tutoring.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A year ago, I saw artificial intelligence as a shortcut to avoid deep thinking. Now, I use it to teach thinking itself.

Like many educators, I initially viewed artificial intelligence as a threat—an easy escape from rigorous analysis. But banning AI outright became a losing battle. This semester, I took a different approach: I brought it into my classroom, not as a crutch, but as an object of study. The results surprised me.

For the first time this spring, my students are not just using AI—they are reflecting on it. AI is not simply a tool; it is a mirror, exposing biases, revealing gaps in knowledge and reshaping students’ interpretive instincts. In the same way a river carves its course through stone—not by force, but by persistence—this deliberate engagement with AI has begun to alter how students approach analysis, nuance and complexity.

Rather than rendering students passive consumers of information, AI—when engaged critically—becomes a tool for sharpening analytical skills. Instead of simply producing answers, it provokes new questions. It exposes biases, forces students to reconsider assumptions and ultimately strengthens their ability to think deeply.

Yet too often, universities are focused on controlling AI rather than understanding it. Policies around AI in higher education often default to detection and enforcement, treating the technology as a problem to be contained. But this framing misses the point. The question in 2025 is not whether to use AI, but how to use it in ways that deepen, rather than dilute, learning.

This semester I’ve asked students to use AI in my seminar on Holocaust survivor testimony. At first glance, using AI to analyze these deeply human narratives seems contradictory—almost irreverent. Survivor testimony resists coherence. It is shaped by silences, contradictions and emotional truths that defy categorization. How can an AI trained on probabilities and patterns engage with stories shaped by trauma, loss and the fragility of memory?

And yet, that is precisely why I have made AI a central component of the course—not as a shortcut to comprehension, but as a challenge to it. Each week, my students use AI to transcribe, summarize and identify patterns in testimonies. But rather than treating AI’s responses as authoritative, they interrogate them. They see how AI stumbles over inconsistencies, how it misreads hesitation as omission, how it resists the fragmentation that defines survivor accounts. And in observing that resistance, something unexpected happens: students develop a deeper awareness of what it means to listen, to interpret, to bear witness.

AI’s sleek outputs conceal a deeper problem: It is not neutral. Its responses are shaped by the biases embedded in its training data, and by its relentless pursuit of coherence—even at the expense of accuracy. An algorithm will iron out inconsistencies in testimony, not because they are unimportant, but because it is designed to prioritize seamlessness over contradiction, clarity over ambiguity. But testimony is ambiguity. Memory thrives on contradiction. If left unchecked, AI’s tendency to smooth out rough edges risks erasing precisely what makes survivor narratives so powerful: their rawness, their hesitations, their refusal to conform to a clean, digestible version of history.

For educators, the question is not just how to use AI but how to resist its seductions. How do we ensure that students scrutinize AI rather than accept its outputs at face value? How do we teach them to use AI as a lens rather than a crutch? The answer lies in making AI itself an object of inquiry—pushing students to examine its failures, to challenge its confident misreadings. AI does not replace critical thinking; it demands it.

If AI distorts, misinterprets and overreaches, why use it at all? The easy answer would be to reject it—to bar it from the classroom, to treat it as a contaminant rather than a tool. But that would be a mistake. AI is here to stay, and higher education has a choice: either leave students to navigate its limitations on their own or make those limitations part of their education.

Rather than treating AI’s flaws as a reason for exclusion, I see them as opportunities. In my classroom, AI-generated responses are not definitive answers but objects of critique—imperfect, provisional and open to challenge. By engaging with AI critically, students learn not just from it, but about it. They see how AI struggles with ambiguity, how its summaries can be reductive, how its confidence often exceeds its accuracy. In doing so, they sharpen the very skills AI cannot replicate: skepticism, interpretation and the ability to challenge received knowledge.

This approach aligns with Marc Watkins’s observation that “learning requires friction.” AI can be a force of productive friction in the classroom. Education is not about seamlessness; it is about struggle, revision and resistance.

Teaching history—and especially the history of genocide and mass violence—often feels like standing on a threshold: one foot planted in the past, the other stepping into an uncertain future. In this space, AI does not replace the act of interpretation; it compels us to ask what it means to carry memory forward.

Used thoughtfully, AI does not erode intellectual inquiry—it deepens it. If engaged wisely, it sharpens—rather than replaces—the very skills that make us human.

Co-Intelligence: Living and Working With AI by Ethan Mollick

Published in April 2024

How many artificial intelligence and higher education meetings have you attended where much of the time is spent discussing the basics of how generative AI works? At this point in 2025, the biggest challenge for universities to develop an AI strategy is our seeming inability to achieve universal generative AI literacy.

Given this state of affairs, I’d like to make a modest proposal. From now on, all attendees of any AI higher education–focused conversation, meeting, conference or discussion must first have read Ethan Mollick’s (short) book Co-Intelligence: Living and Working With AI.

The audiobook version is only four hours and 37 minutes. Think of the productivity gains if we canceled the next five hours of planned AI meetings and booked that time for everyone to sit and listen to Mollick’s book.

For university people, Co-Intelligence is perfect, as Mollick is both a professor and (crucially) not a computer scientist. As a management professor at Wharton, Mollick is experienced in explaining why technologies matter to people and organizations. His writing on generative AI mirrors how he teaches his students to utilize technology, emphasizing translating knowledge into action.

In my world of online education, Co-Intelligence serves as an excellent road map to guide our integration of generative AI into daily work. In the past, I would have posted Mollick’s four generative AI principles on the physical walls of the campus offices that learning designers, media educators, marketing and admissions teams, and educational technology professionals once shared. Now that we live on Zoom and are distributed and hybrid—I guess I’ll have to put them on Slack.

Mollick’s four principles include:

When it comes to university online learning units (and probably everywhere else), we should experiment with generative AI in everything we do. This experimentation runs from course/program development, curriculum and assessment writing to program outreach and marketing.

While anything written (and very soon, visual and video) should be co-created with generative AI, that content must always be checked, edited and reworked by one of us. Generative AI can accelerate our work but not replace our expertise or contribution.

When working with large language models, the key to good prompt writing is context, specificity and revision. The predictive accuracy and effectiveness of generative AI output dramatically improve with the precision of the prompt. You need to tell the AI who it is, who the audience it is writing for is and what tone the generated content should assume.

Today, we can easily work with AI to create lecture scripts and decks. How long will it take to feed the AI a picture of a subject matter expert and a script and tool to create plausible—and compelling—full video lectures (chunked into short segments with embedded computer-generated formative assessments)? Think of the time and money we will save when AI complements studio-created instructional videos. We are around the corner of AI’s ability to accelerate the work of learning designers and media educators dramatically. Are we preparing for that day?

How are your online learning teams leveraging generative AI in your work?

What other books on AI would you recommend for university readers?

What are you reading?

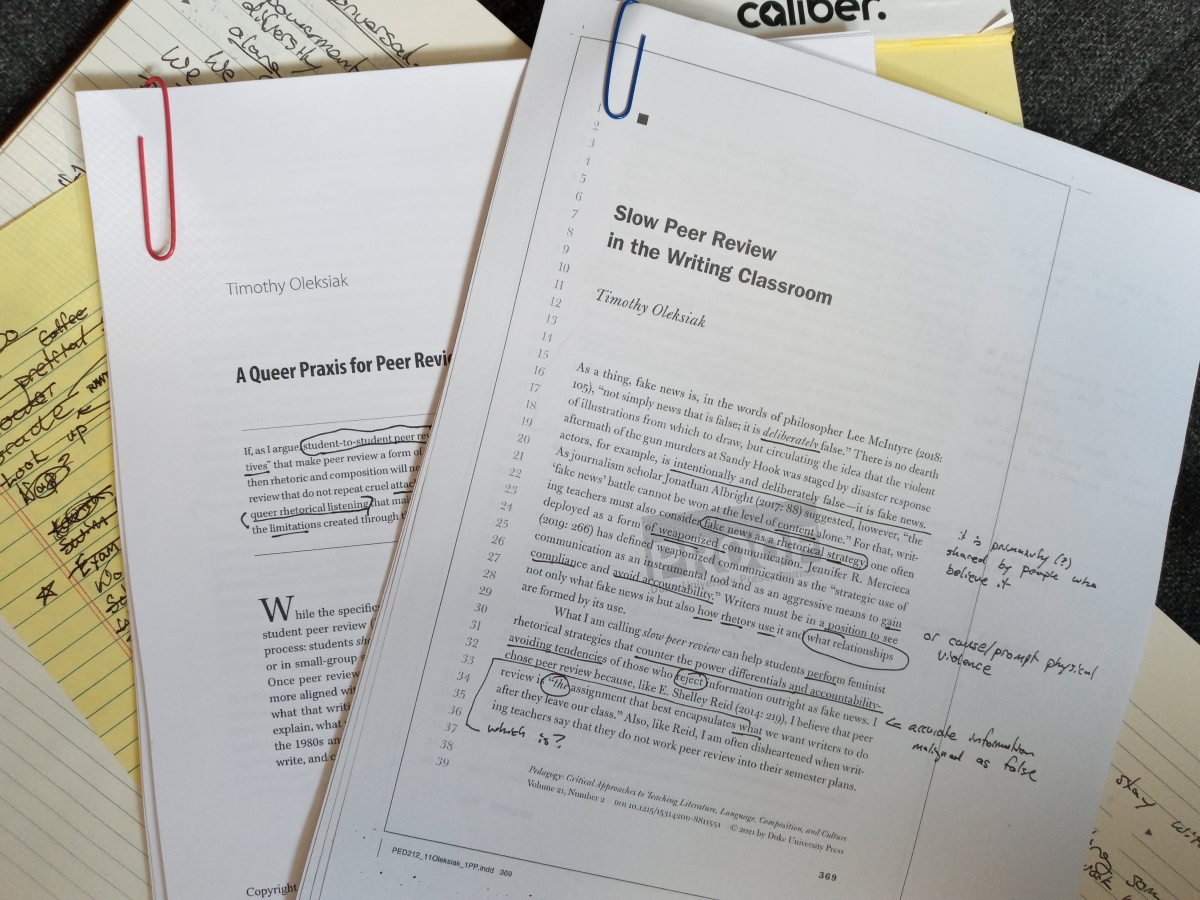

I spoke with Dr. Timothy Oleksiak, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts—Boston, about two of his essays, “A Queer Praxis for Peer Review” and “Slow Peer Review in the Writing Classroom,” recently out in College Composition and Communication and Pedagogy. In these essays, they present theory and practice for a pedagogical practice they call slow peer review, a different way to approach that classical strategy of writing classes, student-to-student peer review, where students swap drafts and give each other feedback on how to improve them. Slow peer review does have students swap drafts but asks them to spend a lot more time with the drafts than usual, reading them very carefully and thinking about them deeply. Slow peer review then asks students to respond in different and more in depth ways than just giving the writer suggestions. I found the essays really compelling, opening up so many questions with relevance far beyond this specific practice and far beyond even just the teaching of writing.

In our conversation, which you can watch below, we discuss opera, “the improvement imperative” (i.e., there are more things to do in a writing classroom than help students write better, even as that remains a key goal), and the concept of “cruel optimism” (which refers, in this case, to an unhealthy attachment to certain teaching strategies that aren’t working and won’t suddenly start working through being tweaked). We also discuss the ways in which writers and readers of drafts both participate in “worldmaking.” The idea here is that each draft someone writes envisions a world in which some are included while others are not, and peer reviewers can help writers imagine more clearly what sort of world they’ve built. We also discuss what all of this has to do with queer theory. Lastly, I asked Timothy whether this peer review pedagogy isn’t actually a reading pedagogy. While he’s not so sure, he does have students “read the drafts five different times” and directs students to consider such questions as “What does it mean to be fully human in this world?” (i.e., in the world of the draft being read). Those seem like scaffolds for deep reading to me. At any rate, whatever else this pedagogy does, it does ask students to really read each other’s writing. And that feels extraordinarily valuable to me.