This blog was kindly authored by Martin Lowe, Professor Adrian Wright, Dr Mark Wilding and Mary Lawler from the University of Lancashire, authors of Student Working Lives (HEPI report 195).

The clearest finding of our recent HEPI report, Student Working Lives, was the growing prevalence of paid work among students and its profound impact on their experiences and outcomes.

This trend is not confined to disadvantaged groups; it is now a reality for the majority of students, with the Advance HE and HEPI Student Academic Experience Survey revealing how 68% of students now work during term time. Yet, despite its significance, paid work remains largely absent from regulatory frameworks designed to promote equality of opportunity in higher education.

As the Office for Students (OfS) reviews its approach to access and participation, we argue that paid work should be recognised as a distinct risk on the Equality of Opportunity Risk Register (EORR). Doing so would enable providers to respond more effectively to the challenges students face and ensure that widening participation efforts reflect the realities of modern student life.

A risk-based future for access and participation

Since taking office, the Labour Government has placed widening participation as a central pillar of its higher education agenda. From the introduction of the Lifelong Learning Entitlement to the creation of a new Access and Participation Task and Finish Group, ministers have signalled their determination to open doors to learners from non-traditional backgrounds.

This ambition was reiterated in the recent Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper, which proposed a significant shift in the regulatory approach in England:

We will reform regulation of access and participation plans, moving away from a uniform approach to one where the Office for Students can be more risk-based.

While this statement attracted less attention than the more headline-grabbing measures on tuition fees and maintenance grants, it represents a potentially transformative change. A risk-based model could allow the OfS to focus on the most pressing barriers to equality of opportunity, provided those risks are accurately identified.

The existing EORR complements this approach. Having been introduced under the leadership of outgoing Director of Fair Access and Participation at the OfS, John Blake, the register has already been widely welcomed by the sector. By identifying factors that threaten access and success for disadvantaged student groups, it enables providers to design interventions tailored to their own context. Rather than simply seeking to address outcome gaps, the EORR encourages institutions to tackle the underlying causes.

However, the register is not static. If it is to remain relevant, it must evolve to reflect emerging challenges. One such challenge is the growing necessity of paid work alongside study, a risk that intersects the financial pressures felt by students but extends far beyond them.

Paid work is more than a financial issue

The current EORR already identifies ‘Cost Pressures’ as a risk, acknowledging that rising living costs can undermine students’ ability to complete their course or achieve good grades. Yet this framing is too narrow on its own. Paid work is not merely a symptom of financial strain; it’s a complex factor that shapes engagement, attainment, and progression into graduate employment.

Our research shows that paid work is a necessity for most students, regardless of background, with average hours worked remaining static across each Indices of Deprivation (IMD) quintile. However, its impact is uneven. Students having to work more than 20 hours per week, those employed in particularly demanding sectors and those balancing caring responsibilities may all face challenges due to increased workload. However each should be supported in different ways.

These patterns matter because they influence both academic performance and participation in enrichment activities that support retention and employability. Paid work is a structural feature of student life that can amplify existing inequalities, but present specific nuances depending on the local context.

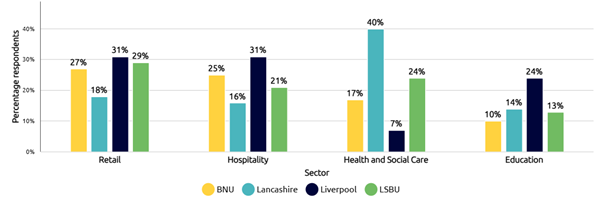

Our analysis highlights how the risks associated with paid work differ across institutions and how regional labour markets shape patterns of student employment. For instance, our survey indicates a higher proportion of students working in health and social care in Lancashire, where the sector represents 15% of total employment. In contrast, Liverpool’s relatively large share of hospitality student workers reflects the sector’s prominence, accounting for around 10% of jobs in the city region. These different contexts can help steer local interventions to reduce risk associated with particular sectors.

Recognising paid work as a formal risk would help empower institutions to develop context-sensitive strategies. These might include the crediting of paid work within the curriculum, embedding guidance on employment rights within pastoral support, or designing schedules that accommodate students’ working patterns.

Access and participation – two sides of the same coin

As the OfS explores separating out the “Access” and “Participation” strands of its regulatory framework – as outlined in their recent quality consultation – paid work should feature prominently in supporting both ambitions. Widening access is not simply about opening the door; it is about ensuring wider groups of students see themselves as being part of that experience. For some mature learners, carers, and those with financial dependencies (who may feel excluded by the traditional delivery model of higher education) the support to balance paid work and study is critical.

Ignoring this reality risks undermining the very goals of widening participation. Higher education must adapt to the evolving profile of its students, who increasingly diverge from the outdated stereotype of the full-time undergraduate.

Our recommendation is for the OfS to prioritise paid work as a key aspect of the future of Access and Participation regulation, inserting it as a distinct risk within the Equality of Opportunity Risk Register. Doing so would:

- signal its importance as a structural factor affecting equality of opportunity;

- enable targeted interventions that reflect institutional and regional contexts;

- support innovation in curriculum design, pastoral care, and timetabling;

- and promote collaboration between universities, employers, and policymakers to improve job quality and flexibility.

This is not about discouraging students from working. For many, employment provides valuable experience and skills. Instead, it is about recognising that when work becomes a necessity rather than a choice, it can compromise educational outcomes, especially for those already at the margins.

The OfS has an opportunity to lead the sector in addressing one of the most pressing challenges facing students today. By treating paid work as a formal risk, it can help ensure that access and participation strategies are grounded in the lived realities of learners.

As we look to the future, one principle should guide the sector: widening participation does not end at the point of entry. It extends throughout the student journey, encompassing the conditions that enable success. Paid work is now not only part of that journey, but a critical factor.