Higher education has always been a multigenerational co-op. A space where different worldviews, values and learning habits collide and evolve together. Right now, universities are still learning how to teach and support Gen Z, students who have redefined expectations around flexibility, purpose and wellbeing.

But just as the sector starts to feel comfortable with these adjustments, the next generation is already forming behind them. “Gen Alpha” – those born from 2010 onwards – will start arriving within the next five years and their presence will make the intergenerational mix even more fascinating, and far more challenging to work with.

Universities are used to responding to disruption when it is forced upon them, whether through policy reform, funding shifts or sudden global shocks. But this time, the change is visible on the horizon. Higher education can see one of its next major disruptions coming years in advance. The question is not whether Gen Alpha will alter how we teach, learn or engage. They will. The question is whether the sector can prepare in time, drawing lessons from what’s already happening with today’s learners.

By 2030, higher education will become an even more complex multi-generational co-op. Gen Alpha students will be learning alongside the tail of Gen Z and quite a few millennials and Generation X. They will be taught by academics largely from the Millennials and Generation X age groups. Each group will bring different digital literacies, communication norms and values into the same ecosystem.

The challenge, and opportunity, will be in creating environments flexible enough to bridge these perspectives while sustaining academic rigour. Understanding Gen Alpha, then, is not about predicting a single generation’s quirks. It’s about preparing universities for a shared future where several generations will need to coexist, collaborate and learn from each other.

No off switch

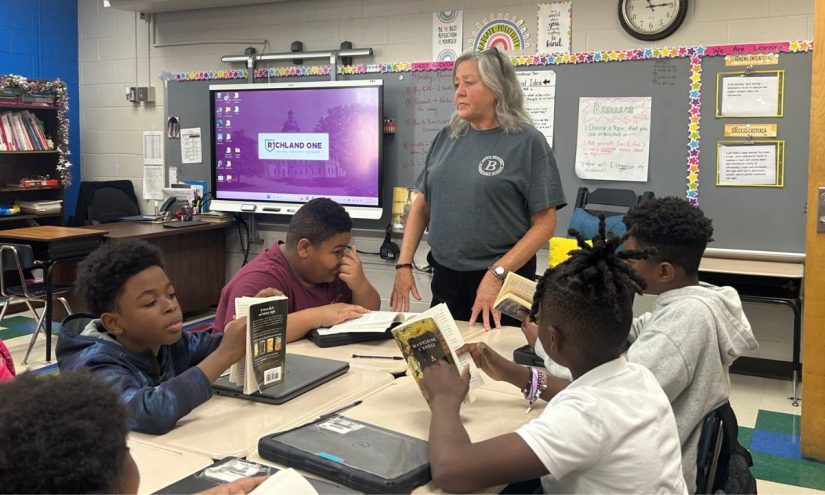

Much of what will define Gen Alpha is already visible in classrooms now. Current higher education students are demanding immediacy, connection and relevance; expectations born in a digital ecosystem that never switches off. Yet Gen Alpha will take these habits to another level. They are growing up with technology not as a tool but as the background hum of existence; seamless, intuitive and always present. They have learned to read, count and solve problems through interactive and gamified environments long before they stepped into a school.

There is a high chance that because of or – depending on your vantage point – thanks to these habits Gen Alpha will be the most self-directed learners higher education has ever seen – but also the least patient with systems that feel slow, static or disconnected from their lived reality. Long feedback cycles, rigid timetables or outdated online platforms won’t just frustrate them; they will feel illogical. The idea of sitting through a two-hour lecture (even online) may seem not just boring but absurd.

The early evidence is already visible in schools. Teachers across the UK talk about declining engagement and rising frustration when lessons are delivered in traditional ways. In the US, teachers describe pupils who question why they are being taught a certain way and struggle to engage with methods that feel prescriptive or irrelevant. In Australia, schools experimenting with more adaptive and project-based models such as NSWEduChat report that students are more motivated when given freedom, agency and connection to real-world issues. This is the mindset that will soon walk through our university doors.

Cultural readiness

Gen Alpha’s world is also more emotionally complex than that of previous generations. They are growing up surrounded by climate anxiety, social awareness and global instability. Unlike many other generations, their exposure to world events is constant and their access to information is, many times, dangerously unfiltered. They form strong opinions early and are not afraid to express them. They value authenticity and expect institutions they interact with to demonstrate values that align with their own. I am rather certain that if higher education speaks in jargon, hides behind hierarchy, or treats them as passive recipients, Gen Alpha will tune out.

This is a generation that has been encouraged to ask questions, to expect answers quickly and to always be heard. They are unlikely to respond well to ecosystems that require silent compliance or delayed gratification considering they are growing up with feedback loops built into everything they do, from online games to learning apps. They are more likely to engage with learning that is immediate, collaborative and visually rich instead of linear or text heavy.

Culturally, Gen Alpha is also more diverse, more inclusive and more globally connected than any generation before them. Many grow up in multilingual homes and navigate multiple cultural identities. Their sense of belonging is not bound by geography but by shared values and interests – imagine the extraordinary opportunities this will bring for HE. But universities need to create environments that feel inclusive, authentic and flexible enough to truly accommodate that diversity.

The challenge then is not simply technological development but cultural readiness. Universities must ask whether the way they structure courses, deliver teaching and define success reflects the world these students live in. Long assessment cycles and stale teaching methods will become relics of an age that made sense when information was scarce and time moved slower.

Foresight

The first wave of Gen Alpha will enter UK universities in 2029 or thereabouts. That is closer to us today than the first pandemic lockdowns are behind us (and 23 March 2020 still feels like yesterday). The window to act is narrow and the sector is already under strain.

The solution is not to rip everything up or abandon academic rigour, but to start prototyping now: testing interactive teaching models, embedding AI into learning processes, creating more authentic and timely assessments, and developing staff confidence to deliver education that resonates with digital native learners. Universities that take these steps will be positioned not just to survive the arrival of Gen Alpha but to thrive with them.

The disruption ahead is unusual in one crucial way – we can see it coming. There will be no excuse for surprise. The next generation of students is telling us (those who listen), every day, what they expect learning to feel like. The question is whether higher education will have the courage, creativity, foresight and capacity to listen – before Gen Alpha decides it no longer needs us.