Several hundred feet from the White House, down a concrete path and across a quiet brick courtyard adorned with historical markers lie the doors to a small courthouse.

Inside, etched into the stone wall, is a quote from Abraham Lincoln: “It is as much the duty of government to render prompt justice against itself, in favor of citizens, as it is to administer the same, between private individuals.”

It’s apt for what’s in this building: the Court of Federal Claims, a legal venue where the U.S. government is always the one being sued. The building is now poised to be the site of fights over droves of terminated research grants.

Although it’s the latest iteration of a court that’s existed since 1855, predating Lincoln’s election, it’s not a well-known institution. It’s not the subject of on-screen, steamy legal dramas. But the U.S. Supreme Court’s preliminary rulings last year have elevated its importance for higher ed.

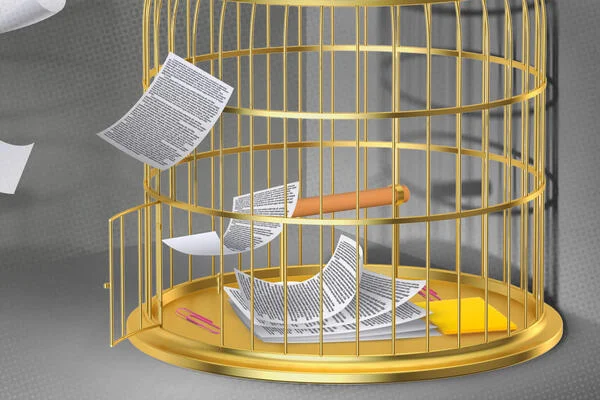

A majority of justices say this 16-judge court likely has jurisdiction over lawsuits regarding thousands of National Institutes of Health federal research grants that the Trump administration has tried to terminate, as well as other fights concerning canceled grants. If the Supreme Court sticks by its current thinking in final rulings, the Court of Federal Claims could be handling fights over countless grants that the Trump administration and future higher ed-targeting presidencies may try to cancel in the future.

One catch: This court doesn’t have the authority to actually restore the grants. It can award money for canceled ones, but experienced lawyers who practice before it disagree on whether it will provide compensation even approaching what the grants were worth—they can be for millions of dollars apiece.

Attorneys also say that researchers likely won’t have the right in this court to challenge their grant terminations; they’ll have to rely on their universities to sue on their behalf because the institutions are the legal parties to research grants. Overall, it’s generally unclear how a research grant-related case would turn out in this court.

“This is—I think esoteric is probably an understatement,” said Bob Wagman, president of the Court of Federal Claims Bar Association and a lawyer before the court for 25 years.

Lobby of the United States Court of Federal Claims building.

Ryan Quinn/Inside Higher Ed

‘A Mess’

As far as Wagman knows, the court has yet to say what level of monetary damages plaintiffs could win from the court over research grant terminations. He said that’s just one of a number of “threshold” issues judges will have to decide on regarding how these cases will work.

“It’s just been sort of an avalanche and people are trying to figure out what makes the most sense,” Wagman said.

Ted Waters, the managing partner at Feldesman LLP and a George Washington University Law School adjunct professor, said “it’s all a mess because nobody knows what the rules are.”

He contends that plaintiffs before this court couldn’t win back the full value of their grants but instead only “out-of-pocket termination costs,” such as the expense of giving two weeks’ severance pay to employees a university hired in expectation of receiving the grant. He said Congress didn’t create the Court of Federal Claims and the special appeals court that’s over it to deal with federal grants; it’s meant for contracts, such as when the government purchases items from companies.

“This is all new stuff, and none of the kinks have been worked out,” said Waters, who’s been working in the federal grants field since 1992.

Heather Pierce, senior director of science policy for the Association of American Medical Colleges, said thousands of terminated NIH grant cases going to the Court of Federal Claims “would clog the court immediately.” Elizabeth Hecker, a senior counsel with specialty in higher ed for Crowell & Moring LLP, echoed that.

“There’s gonna be a tremendous backup … and these are gonna take years and years and years to decide,” Hecker said. “Whereas, if you go to federal district court, you can get a preliminary injunction.”

But Waters doubts there will be a flood of cases. He said there’s little to fight over because researchers can’t get the relief they want from the court.

The [Supreme] Court grapples with none of these complexities before sending plaintiffs through the labyrinth it has created.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson

Anuj Vohra, a partner at Crowell & Moring LLP, who began his career in Washington working for the Justice Department before the court, said “the court does not have equitable powers to reinstate grants, and I think that is, in large part, why the government is trying to move much of this litigation to the court.”

He said plaintiffs will have to expend resources to win in this court and, while “we don’t know exactly how the Department of Justice is going to defend these grant terminations, … I assume they’re going to argue that the researchers are entitled to something less than the entire amount of the grant.”

Still, Vohra said he doesn’t think going to the court would be pointless.

“Grant terminations have not historically been litigated in the Court of Federal Claims, and so the challenges we’re seeing now are kind of charting a new course in terms of damages, theories and entitlement,” he said. “But I certainly don’t think it’s a fool’s errand to come to the court, and I think we’re going to see a lot more litigation over grant terminations this year.”

Courtyard of the U.S. Court of Federal Claims building. Lincoln’s secretary of state lived and was almost assassinated at this site.

Ryan Quinn/Inside Higher Ed

‘The Labyrinth’

Not all the Supreme Court justices thought this was a good idea.

The conservative majority, absent Chief Justice John Roberts, first mentioned the Court of Federal Claims last year in one line in a roughly two-page preliminary ruling in April.

“The Tucker Act grants the Court of Federal Claims jurisdiction over suits based on ‘any express or implied contract with the United States,’” the majority wrote, reasoning that canceled Education Department K-12 teacher training grants in that case were contracts.

There was only one justice, and that’s Amy Coney Barrett, who thought that that was the right outcome.”

Elizabeth Hecker, senior counsel with Crowell & Moring LLP

Then, in August, in ongoing litigation over the Trump administration’s termination of thousands of NIH research grants, Justice Amy Coney Barrett was the deciding vote. In a five-page preliminary opinion, she said a regular federal district court “likely lacked jurisdiction to hear challenges to the grant terminations, which belong in the Court of Federal Claims.” In a partial concurrence with Barrett, Justice Neil Gorsuch criticized the lower court judge—who had ruled the grants should be reinstated while the case continued—for not following the conservative majority’s earlier (also preliminary) ruling in the Education Department lawsuit.

“Lower court judges may sometimes disagree with this Court’s decisions, but they are never free to defy them,” Gorsuch wrote. He said that, even though the decision in the Education Department case wasn’t a final judgment, “when this Court issues a decision, it constitutes a precedent that commands respect in lower courts.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson countered in a 20-page dissent that “the Court of Federal Claims is authorized to award only money damages for contract breaches, not reinstatement of grant funding improperly terminated in violation of federal law.” She defended the district court’s decision.

“Having struck down unlawful agency action, the District Court ‘also had the authority to grant the complete relief’ that followed,” Jackson wrote, quoting precedent. “Under the rule the Court announces today, however, no court can reinstate the plaintiffs’ grants.” In a footnote, she added that “the Court grapples with none of these complexities before sending plaintiffs through the labyrinth it has created.”

A plaque outside the United States Court of Federal Claims building.

Ryan Quinn/Inside Higher Ed

Barrett concluded in her August decision that the district court did likely have the right to void the NIH guidance upon which the agency based its terminations, even though it likely didn’t have the right to restore the grants. But four of Barrett’s colleagues said the district court was likely wrong on both issues, while the other four said the district court was likely right on both.

That meant Barrett was the deciding vote on a split order that allowed universities, researchers and other organizations to challenge the guidance in district court, but said they had to challenge the actual grant terminations in the Court of Federal Claims.

“There was only one justice, and that’s Amy Coney Barrett, who thought that that was the right outcome,” said Hecker, of Crowell & Moring LLP. She said “it’s a very unusual and seemingly inefficient way to go about doing things.”

Hecker said one way to avoid this dual-track litigation would be for plaintiffs challenging grant terminations to use constitutional arguments—such as claiming that grant cancellations violate the First Amendment—rather than the Administrative Procedure Act, a law cited in the NIH grants case that invited the counter-argument from the government that the cases belonged in the Court of Federal Claims.

Waters, of Feldesman LLP, said the ramifications of sending grant cases to the Court of Federal Claims extend far beyond higher ed, to highways, green technology and more.

“The importance of grant programs—I don’t think people realized until now,” he said, adding that they “touch the whole fabric of American society.”

Wagman, the president for the court’s bar association, said he thinks that, given the uncertainty of how claims for money before the court will turn out, most people would just prefer their grants be reinstated.

“But if that’s all you got,” he said, “that’s all you got.”