“You have two ears, one mouth – use them in that proportion.”

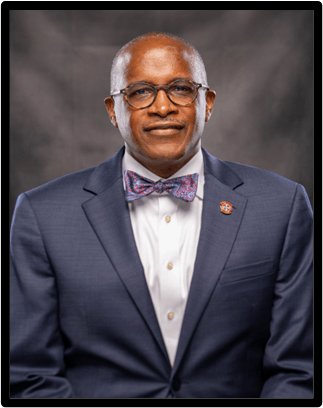

The words of my mother seem to have gained relevance and resonance for me, as I reflect at the end of my tenure as CEO responsible for overseeing the launch of Medr, the new tertiary funding and regulatory body in Wales.

As we arrive at our first birthday as an organisation, my mother’s words ring true in the approach we have tried to nurture with partners to help tackle the challenges and embrace the opportunities facing the sector.

And this is perhaps particularly true during the well-established perfect storm of headwinds facing our higher education institutions at present, prompting understandable deliberations and concern around staffing, provision and campus restructuring.

Wonkhe readers will be well versed in the plethora of pressures facing even the most long-established and most renowned universities across the UK. Put simply, the pressures of increasing costs are currently not being met by an increase in income for too many, and our institutions in Wales are no different (further context and a Medr perspective were provided to the Senedd’s Children, Young People and Education Committee a few short weeks ago, if it’s of interest).

For the long-term viability of the post 16 sector to thrive in Wales, finding strategic, joined-up solutions is imperative. As a regulator and funder and having engaged extensively with the sector since day one, our analysis is that no institution in Wales is at immediate risk of collapse, but that medium-term outcomes do cause us concern if well thought-through changes are not made.

Beyond “competition with a smile”

What’s also clear to us in Wales is that many of these pressures are also affecting other parts of the tertiary sector – local authorities, schools, further education colleges, apprenticeship providers, adult education providers as well as universities and everything in between.

This, however, can create opportunities.

Back to the words of my mother – “two ears and one mouth” – during our first year of operation as Medr, we have had to quickly get on top of the tertiary issues in Wales. In Stephen Covey’s words, we must “seek first to understand”. We must understand the extent and context of the challenges and why certain actions are being proposed. Through a genuine commitment to engaging with a range of stakeholders and considering how we can facilitate a culture of listening, learning and collaborating across the post-16 sector, we have a great opportunity to build on the solid foundations of a shared ambition and purpose to build resilience for the future.

Being a regulator and a funder is not an end in itself. To be honest, I had underestimated the importance of our role in convening and facilitating conversations between different stakeholders whilst respecting institutional autonomy. Colleagues must be bored of me telling the story of an ex-colleague of mine who challenged me after a meeting when I talked about collaboration. He said:

Do you mean collaboration? Or are you talking about competition with a smile?

We’ve all been there! We smile and nod in a meeting when we talk about working together – and then go back to our respective ranches and nothing changes.

However, if we genuinely place learner need ahead of institutional need, we have an opportunity to create a system that is better than the sum of its parts. Don’t get me wrong, as a former CEO of a post-16 provider, I’m fully aware of the accountability to a governing body and the need to protect the viability of the organisation. But I also acknowledge that I was probably more comfortable in exploring growth and new opportunities, rather than thinking about stopping some things we did because someone else was in a better place to provide that service to our community or region. Collaboration is also not an end in itself – there is no point in collaborating if it just appeases everybody but doesn’t improve the breadth or quality of provision for learners or improves the system as a whole.

A course through the headwinds

At Medr, we have tried to live our values and engage, listen and collaborate with the sector. For example, our first strategic plan has developed considerably through consultation. We have recently launched a consultation on our draft regulatory framework, a hugely important piece of work for the sector, and we will continue to listen throughout that process.

What I hope shines through in that work, and which I equally hope isn’t lost in wider discussions around headwinds and pressures, is the positive everyday impact that all parts of the tertiary sector have on our learners and our communities. I have a huge respect for the learner focussed people who work in our wonderfully diverse post-16 sector. Developing that mutual respect amongst all parts of the sector is vital if we are to develop a better system in the future that can tackle some of the challenges, such as the numbers not in education, employment or training, and our desire to improve participation rates in higher levels of learning.

This isn’t easy. If it was, we would have solved these challenges by now. It has taken decades to create these issues and they won’t be solved overnight. And true collaboration – not competition with a smile! – takes time to build trust, requires a great deal of commitment along with a good dollop of inspiring and tenacious leadership.

Yes, it’s challenging – but therein lies opportunity for innovation. In my experience, when the going gets tough, leaders demonstrate two basic types of behaviour. They either sharpen the elbows and dig in and become even more competitive or they reach out to others and work collectively to find joined up solutions to problems. To achieve the latter, we need to look at ways we can remove the barriers to this approach. Get it right and we can build prosperous futures for our learners and the tertiary education system and for Wales.

There may often be differing views on how best to achieve outcomes but by working together to identify challenges and opportunities, consulting and engaging in solution-based conversations that benefit our learners, we can and will overcome them. Nelson Mandela said that education is “the most powerful weapon you can use to change the world” – we are fortunate in Wales to have some brilliant people coming together to try to deliver that change for good.

Indeed, the name Medr itself is not an acronym. It’s a Welsh word which roughly translated straddles ability, skill and capacity. It’s a name that acts as a reminder of what we’re here to achieve: to ensure all learners can access opportunities to learn new skills and expand their opportunities for the greater good.

And, of course, that greater good extends beyond learners and their immediate surroundings. I continue to be impressed by the work many of our universities deliver through groundbreaking research and innovation. Research Excellence Framework recently recognised 89 per cent of Welsh research as internationally excellent or world leading in its impact. Successful recent spin-outs such as Draig Therapeutics are further examples of world-class research leading to significant impacts of R&I and serve as a reminder that our universities are critical to our economy, society and culture – both now and in the future.

And we are very proud too of our commitment to the Welsh language. The legislation identifies the Coleg Cymraeg Cenedlaethol as the designated advisor to Medr on Welsh language delivery in the post-16 sector. Our two organisations have developed a strong working relationship and through engagement with the sector, we will deliver a national plan for Welsh language delivery.

Reaching out

All this can all only be successfully achieved by working together. It is easy to be a spectator sniping from the sidelines but we must focus on having the right people and systems in the arena to make positive collaborative change. Across the board we must think beyond borders – sectoral, governmental, regional, national and international – listening to and reaching out to others with similar challenges to us. I am heartened by the willingness we’ve seen across the tertiary sector to do just this.

For our part we will continue to facilitate progress by working with stakeholders to understand risks and plans, provide support and challenge based on different situations, ensure governments are well-informed and understand the challenges and opportunities as early as possible – and a whole host besides. It’s both an opportunity and a duty to bring people together and think about how we can do things differently and how we can do things better.

I’ll finish where I started, by talking about my Mam and my upbringing. Growing up in an area that would be described as “socially deprived”, and losing my Dad while still at primary school, it’s very clear to me now the difference a few key educational touchpoints made to my life. I was fortunate to have some teachers along my journey who could see something in me when I couldn’t see it myself. Medr wants to be part of ensuring that such positive educational experiences can be felt by all.

Medr is celebrating its first birthday. We are new kids on the block. And as I hand over to the excellent James Owen, Medr’s new CEO, I recognise that we have launched at a particularly challenging time for the sector.

But among all the noise around business resilience, longevity and political headwinds, it’s absolutely imperative that every conversation comes back to what is right for our learners, the ones who will determine our future successes or failures. Now the exciting bit begins. If we work together to get the system right for our learners – and that’s absolutely at the forefront of what we are trying to shape at Medr – the rest can and will stem from there.