by Nosakhere Griffin-EL, The Hechinger Report

January 5, 2026

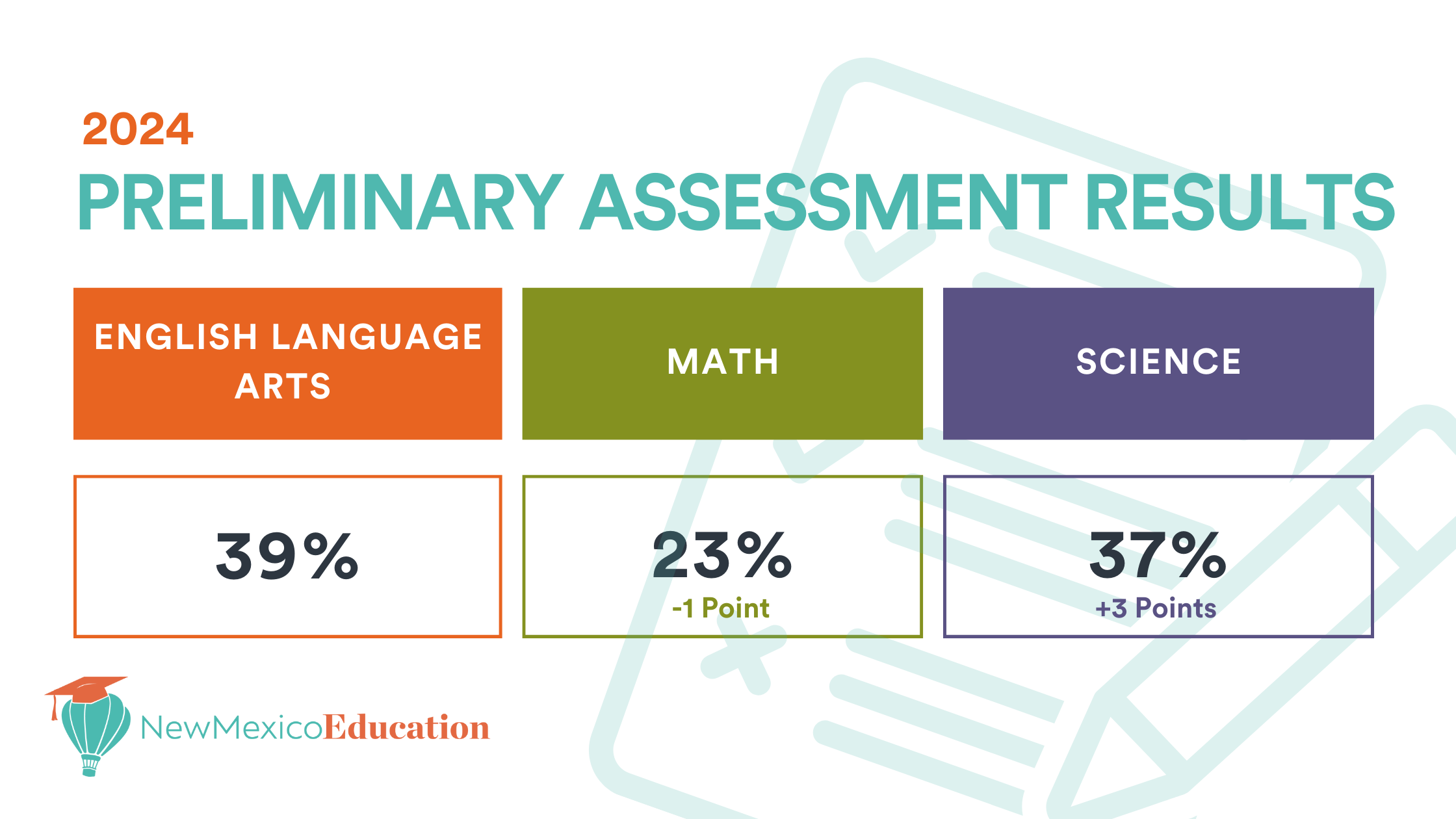

Across the U.S., public school districts are panicking over test scores.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress, or the Nation’s Report Card, as it is known, revealed that students are underperforming in reading, with the most recent scores being the lowest overall since the test was first given in 1992.

The latest scores for Black children have been especially low. In Pittsburgh, for example, only 26 percent of Black third- through fifth-grade public school students are reading at advanced or proficient levels compared to 67 percent of white children.

This opportunity gap should challenge us to think differently about how we educate Black children. Too often, Black children are labeled as needing “skills development.” The problem is that such labels lead to educational practices that dim their curiosity and enthusiasm for school — and overlook their capacity to actually enjoy learning.

As a result, without that enjoyment and the encouragement that often accompanies it, too many Black students grow up never feeling supported in the pursuit of their dreams.

Related: A lot goes on in classrooms from kindergarten to high school. Keep up with our free weekly newsletter on K-12 education.

Narrowly defining children based on their test scores is a big mistake. We, as educators, must see children as advanced dreamers who have the potential to overcome any academic barrier with our support and encouragement.

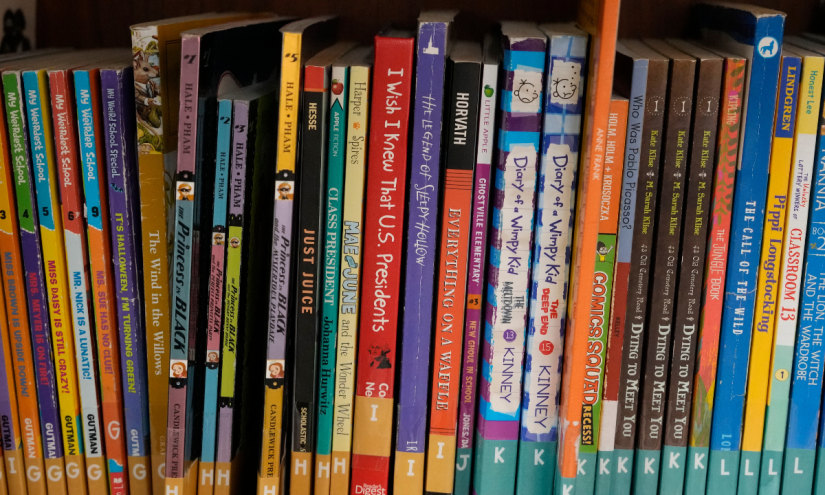

As a co-founder of a bookstore, I believe there are many ways we can do better. I often use books and personal experiences to illustrate some of the pressing problems impacting Black children and families.

One of my favorites is “Abdul’s Story” by Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow.

It tells the tale of a gifted young Black boy who is embarrassed by his messy handwriting and frequent misspellings, so much so that, in erasing his mistakes, he gouges a hole in his paper.

He tries to hide it under his desk. Instead of chastening him, his teacher, Mr. Muhammad, does something powerful: He sits beside Abdul under the desk.

Mr. Muhammad shows his own messy notebook to Abdul, who realizes “He’s messy just like me.”

In that moment, Abdul learns that his dream of becoming a writer is possible; he just has to work in a way that suits his learning style. But he also needs an educator who supports him along the way.

It is something I understand: In my own life, I have been both Abdul and Mr. Muhammad, and it was a teacher named Mrs. Lee who changed my life.

One day after I got into a fight, she pulled me out of the classroom and said, “I am not going to let you fail.” At that point, I was consistently performing at or below basic in reading and writing, but she didn’t define me by my test scores.

Instead, she asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

I replied, “I want to be like Bryant Gumbel.”

She asked why.

“Because he’s smart and he always interviews famous people and presidents,” I said.

Mrs. Lee explained that Mr. Gumbel was a journalist and encouraged me to start a school newspaper.

So I did. I interviewed people and wrote articles, revising them until they were ready for publication. I did it because Mrs. Lee believed in me and saw me for who I wanted to be — not just my test scores.

If more teachers across the country were like Mrs. Lee and Mr. Muhammad, more Black children would develop the confidence to pursue their dreams. Black children would realize that even if they have to work harder to acquire certain skills, doing so can help them accomplish their dreams.

Related: Taking on racial bias in early math lessons

Years ago, I organized a reading tour in four libraries across the city of Pittsburgh. At that time, I was a volunteer at the Carnegie Library, connecting book reading to children’s dreams.

I remember working with a young Black boy who was playing video games on the computer with his friends. I asked him if he wanted to read, and he shook his head no.

So I asked, “Who wants to build the city of the future?” and he raised his hand.

He and I walked over to a table and began building with magnetic tiles. As we began building, I asked the same question Mrs. Lee had asked me: “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

“An architect,” he replied.

I jumped up and grabbed a picture book about Frank Lloyd Wright. We began reading the book, and I noticed that he struggled to pronounce many of the words. I supported him, and we got through it. I later wrote about it.

Each week after that experience, this young man would come up to me ready to read about his dream. He did so because I saw him just as Mr. Muhammad saw Abdul, and just like Mrs. Lee saw me — as an advanced dreamer.

Consider that when inventor Lonnie Johnson was a kid, he took a test and the results declared that he could not be an engineer. Imagine if he’d accepted that fate. Kids around the world would not have the joy of playing with the Super Soaker water gun.

When the architect Phil Freelon was a kid, he struggled with reading. If he had given up, the world would not have experienced the beauty and splendor of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

When illustrator Jerry Pinkney was a kid, he struggled with reading just like Freelon. If he had defined himself as “basic” and “below average,” children across America would not have been inspired by his powerful picture book illustrations.

Narrowly defining children based on their test scores is a big mistake.

Each child is a solution to a problem in the world, whether it is big or small. So let us create conditions that inspire Black children to walk boldly in the pursuit of their dreams.

Nosakhere Griffin-EL is the co-founder of The Young Dreamers’ Bookstore. He is a Public Voices Fellow of The OpEd Project in partnership with the National Black Child Development Institute.

Contact the opinion editor at [email protected].

This story about Black children and education was produced byThe Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’sweekly newsletter.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-instead-of-defining-black-children-by-their-test-scores-we-should-help-them-overcome-academic-barriers-and-pursue-their-dreams/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org”>The Hechinger Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/hechingerreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/cropped-favicon.jpg?fit=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://hechingerreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=114013&ga4=G-03KPHXDF3H” style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-instead-of-defining-black-children-by-their-test-scores-we-should-help-them-overcome-academic-barriers-and-pursue-their-dreams/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/hechingerreport.org/p.js”></script>