Republicans in red states have been attacking diversity, equity and inclusion in higher education for years. But when Donald Trump retook the White House and turned the federal executive branch against DEI, blue-state academics had new cause to worry. A tenured law professor in the University of California system—who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation and harassment—said they read one of the executive orders that Trump quickly issued on DEI and anticipated trouble.

“Seeing how ambiguous it is with respect to how they are defining diversity, equity and inclusion, and understanding that the ambiguity is purposeful, I decided to take off from my [university website] bio my own specialty in critical race theory, so that I would not be a target either of the [Trump] administration or of the people that they are empowering to harass,” the professor said.

The professor said they also told their university they’re not interested in teaching a class called Critical Race Theory for the rest of the Trump administration. They said they faced harassment for teaching it even before Trump returned to the presidency. “A lot of law schools also have race in the law classes, we have centers that are focused on race,” the professor said. “And so all of these kinds of centers and people are really, really concerned—not just about their research, but really, again, about themselves—what kind of individualized scrutiny are they going to get and what’s going to happen to them and their jobs.”

Given all that, self-protection seemed important. “Things are going to get much worse before they get better,” the professor said, adding that “people are very scared to draw attention to their work if they’re working on issues of race. People like me are pre-emptively censoring themselves.”

Other faculty, though, say they’re freshly emboldened to resist the now-nationalized DEI crackdown. One with tenure declared it’s time to “take it out and use it.” Inside Higher Ed interviewed a dozen professors for this article, including some at institutions that have seen changes since Trump’s return to office, to see how the crackdown is, or isn’t, affecting them and their colleagues. Their responses range from defiance to self-censorship beyond what Trump’s DEI actions actually require, but all share concern about what’s yet to unfold.

Diversity, Equity and Confusion

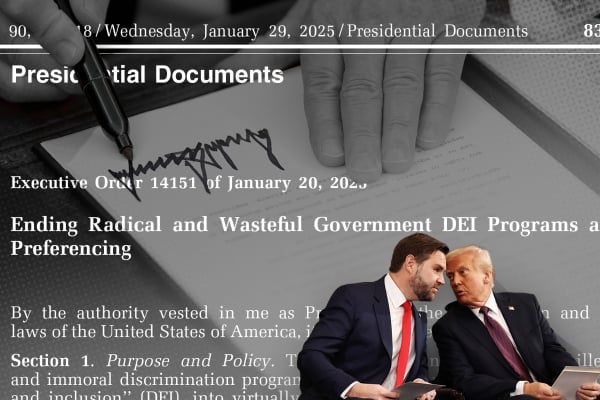

Trump’s efforts to eradicate DEI began on Inauguration Day, with the returning president issuing an executive order that called for terminating “all discriminatory programs, including illegal DEI” across the federal government. The dictate went on to state that these activities must be stamped out “under whatever name they appear.”

That order didn’t specifically mention higher education, but the one Trump signed the following day did. It directed all federal agencies “to combat illegal private-sector DEI” programs, demanding that each agency identify “potential civil compliance investigations”—including of up to nine universities with endowments exceeding $1 billion.

That was Week One. Week Two began with news of a DEI-related funding freeze whose scope was simultaneously sweeping and confusing. A White House Office of Management and Budget memo told federal agencies to pause grants or loans. The office said it was trying to stop funding activities that “may be implicated by the executive orders,” including DEI and “woke gender ideology.”

Federal judges swiftly blocked this freeze. The Trump administration rescinded the memo. Nevertheless, the White House press secretary wrote on X that “This is NOT a rescission of the federal funding freeze.”

The White House didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article. While college and university DEI administrators and offices may feel the brunt of the anti-DEI crusade as these positions and entities are eliminated, the campaign could also cast a pall over faculty speech and teaching.

“This administration does not seem to care about the Constitution or about the existing law,” the anonymous law professor said, adding that “I think, unlike ever before in my own lifetime, I don’t feel safe or secure or I don’t feel the safety of the Constitution in the way that I have in the past.”

Vice President JD Vance has called professors “the enemy.” The professor said this “has really empowered a lot of civil society to see us as the problem.”

But Jonathan Feingold, an associate professor at the Boston University School of Law who’s on the cusp of earning tenure and says he’ll continue to teach critical race theory, is counseling against what he and others have called “anticipatory obedience” to Trump.

“What I am seeing anecdotally reported across the country is universities either scrubbing websites or even potentially shuttering programs or offices,” Feingold said. But he said of the Jan. 21 anti-DEI executive order that “with respect to DEI, there is nothing in it that I see that requires universities to take any action. It certainly is rhetorically jarring and should be understood as a threat, but I don’t see anything that should compel institutions to do anything.”

“The executive order does not define what Trump is saying is unlawful,” Feingold said. He noted it “almost always is attaching to DEI the term ‘illegal’ or ‘unlawful’ or ‘discriminatory’—which, I believe, is a recognition that DEI-type policies of themselves are not unlawful.” He said the order “rehearses the same racist-laden, homophobic-laden, anti-DEI talking points that the Trump administration loves to go to, but, if you read it closely, it reveals that even the Trump administration recognizes that under existing federal law, most of the DEI-type programs that universities have around the country are wholly lawful.”

The bottom of that executive order also lists a few carve-outs that may limit the impact on classrooms. The exceptions say the order doesn’t prevent “institutions of higher education from engaging in First Amendment–protected speech,” nor does it stop educators at colleges and universities from, “as part of a larger course of academic instruction,” advocating for “the unlawful employment or contracting practices prohibited by this order.”

While Feingold said the order doesn’t have teeth, he nevertheless thinks “it’s a very, very dangerous moment right now for faculty members to do their job because the administration is making very clear that it is not OK with any political opposition.” But, he said, “Voluntary compliance is a foolish strategy, given that Trump has telegraphed that he views an independent, autonomous higher education as an enemy. And so I think it’s foolish to think that scrubbing some words on a website are going to satiate what appears to be a desire to suppress any sort of dissenting speech.”

Still, scrubbing is happening.

Scrubbing Words

A few days after Trump’s executive orders, Northeastern University, also in Boston, changed the page for its Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion to instead say “Belonging at Northeastern.” Northeastern spokespeople didn’t explain to Inside Higher Ed why the institution took this step; its vice president for communications said in a statement that “while internal structures and approaches may need to be adjusted, the university’s core values don’t change. We believe that embracing our differences—and building a community of belonging—makes Northeastern stronger.”

In an interview with Inside Higher Ed, Kris Manjapra, the university’s Stearns Trustee Professor of History and Global Studies, declined to speak specifically to what’s happening at Northeastern “because I just don’t have a clear sense of what’s happening.” But, nationally, Manjapra said, “We are witnessing a series of challenges to academic freedom” and witnessing the rise of “what seems to be a fascist coalition, and we are clearly seeing the beginning of reprisals against different institutions that are essential to the functioning of democracy.”

“Although the current language of the attack is being framed as the crackdown on DEIA,” Manjapra said, using the longer initialism for diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility, he said he thinks that’s a “shroud” for what will likely “become a wider attack on the very foundations of what we do at universities—fundamentally, the practice of scientific inquiry and pursuit of ethical reflection.” He also said there’s a larger “attack on democracy and on civil society” in the offing.

“Part of my research has been on the context of German-speaking Europe, and what was happening in the 1920s, in the 1930s, in Germany, and it’s chilling to see patterns from the past return—especially the attack on universities and on free speech and on books,” Manjapra said.

But he said he’s not being chilled; quite the opposite. “The only change that may happen is that I will just be speaking more boldly,” Manjapra said. He said this is “an attack on the very essence of our purpose as academics. And in the face of that attack, the only thing that can be done is to face it head-on.”

In the Midwest, a Republican-controlled state that already cracked down on DEI now appears to be going further, according to one faculty member. An untenured Iowa State University assistant professor—who said he wished to remain anonymous for fear of exposing colleagues to retaliation and for fear of colleagues limiting their future communication—said he attended a town hall meeting for his college last week after Trump’s executive orders. While state legislators had already banned DEI offices across Iowa’s public universities, the assistant professor said his dean now said more action was required.

“Our directive is to eliminate officers and committees with DEIA missions in governance documents and remove language from strategic plan documents about DEIA objectives, and plans for both those are underway across the university,” the professor said. He said, “We know from state politics that state legislators and the governor’s office are going to be looking for workarounds, so they’re not just interested in the literal language, they’re going to be looking probably to see if there’s any way that people are trying to linguistically skirt the specific requirements.”

The professor said his dean guessed “we have something like two weeks to make these changes.” In an emailed response to Inside Higher Ed’s questions, an Iowa State spokesperson said simply that the university “continues to work with the Iowa Board of Regents to provide guidance to the campus community on compliance with the state DEI law,” without mentioning any role Trump’s recent actions may be playing.

As for his own teaching, the Iowa professor said, “I don’t intend to change my own curriculum.” He said, “There are classes that I regularly teach that the current content of which would almost certainly get me into trouble.” He said, “I’m asking myself now, ‘What would I be willing to lose my job for?’ and, ‘What would our administrators and university leadership be willing to lose their jobs for?’”

On Thursday, a communications officer for the Georgia Institute of Technology’s School of Interactive Computing sent out an email saying that “Georgia Tech communicators, including myself, have been directed to delete all content that contains any of the following words that are in the context of DEI from any Georgia Tech affiliated website,” including “DEI,” all the words that make up DEI, “inclusive excellence” and “justice.”

“Unfortunately, this will result in the deletion of dozens of stories that I and previous communications officers have written,” he wrote. He also said that the faculty hiring page had been taken down and would remain down until faculty and staff “submit new copy” for that page.

Faculty shared this communication online, expressing concerns and debating what it meant. Dan Spieler, an associate psychology professor at Georgia Tech, said the threats of universities not getting research grant funding “has the potential to blow a massive hole in Georgia Tech’s budget—a massive hole in, like, everyone’s budget.” So, he said that, among administrators, “my guess is that there’s a lot of discussion about how do we stay off the radar, how do we keep the grants flowing?”

(In an emailed statement to Inside Higher Ed, a Georgia Tech spokesperson said, “As a critical research partner for the federal government, Georgia Tech will ensure compliance with all federal and state rules as well as policies set by the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia to continue accelerating American innovation and competitiveness. Efforts to examine and update our web presence are part of this ongoing work.”)

At institutions with weak faculty governance such as Georgia Tech, Spieler said, “administrators will largely have free rein, at least in the first pass” for deciding how to respond. But, when it comes to his own teaching, he said, “I’m not going to change a goddamn thing, because I have tenure and if you don’t take it out and use it once in a while, then, you know, what’s the point?”

“I think we’re going to find out who truly was actually interested and committed to ideals like diversity, equity and inclusion, and who was just paying lip service to it,” he said.

Dànielle DeVoss, a tenured professor and department chair of writing, rhetoric and cultures at Michigan State University—which made headlines over canceling and then rescheduling a Lunar New Year event after Trump retook the presidency—said, “I think we’re in the midst of a deliberate, strategic campaign of generating fear and anxiety.” She suggested faculty and administrators may have to respond to Trump’s DEI crackdown differently.

“I suspect university-level messaging has to be much more nuanced,” DeVoss said. “I mean, we’re a public institution. Individual faculty and academic middle managers like myself have, I think, more wiggle room to be activists and advocates. But our top-level administration, their responsibility is to protect our institution, our funding, our budgets.” However, she said, “faculty have academic freedom, and of course freedom of speech, protecting our individual actions.”