This story is part of Hechinger’s ongoing coverage about rethinking high school. See our articles about a new diploma in Alabama, a “career education for all” model in Kentucky, and high school apprenticeships in Indiana.

BELOIT, Wis. — As Chris Hooker eyed a newly built piece of ductwork inside Beloit Memorial High School, a wry smile crept over his face. “If you worked for me,” he told a student, considering the obviously crooked vent, “I might ask if your level was broken.”

Hooker, the HVAC manager of Lloyd’s Plumbing and Heating Corp. in nearby Janesville, was standing inside a hangar-sized classroom in the school’s advanced manufacturing academy, where students construct full-size rooms, hang drywall and learn the basics of masonry. His company sends him to the school twice a week for about two months a year to help teach general heating, venting and air conditioning concepts to students.

“I cover the mountaintop stuff,” he said, noting that at a minimum students will understand HVAC when they become homeowners.

But the bigger potential payoff is that these students could wind up working alongside Hooker after they graduate. If his firm has an opening, any student recommended by teacher Mike Wagner would be a “done deal,” Hooker said. “Plus, if they come through this class, I know them.”

Manufacturing and construction dominate the business needs inside Beloit, a small city of 36,000 just minutes from the Illinois border. Sitting at the nexus of two major highways, and within 100 miles of Chicago, Milwaukee and Madison, Beloit is home to a range of businesses that include a Frito-Lay production plant, an Amazon distribution center and a Navy subcontractor. In the next two years, a $500 million casino and hotel complex is scheduled to open.

But staffing these companies into the future is a major concern. Across the country, the average age of manufacturing workers is increasing, and one in four of these workers is age 55 or older, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2021 figures, the most recent available. In many other jobs the workforce is aging, too. Wisconsin is one of several states looking to boost career and technical education, or CTE, as a possible solution to the aging and shrinking workforce.

While the unemployment rate of Rock County, which includes Beloit, is 3.6 percent, only slightly higher than the state’s 3.2 percent, there’s a worker mismatch in the city, according to Drew Pennington, its economic development director.

Every day, 14,000 city residents travel outside of Beloit to work, while the same number commute into the city to fill mostly higher-paying jobs, said Pennington.

So when Beloit decided to revamp its public high school in 2018, CTE and work-based learning were at the forefront of the transformation.

The 1,225-student school now has three academies that cover 13 different career paths. After ninth grade, students choose to concentrate in an area, which means taking several courses in a specific field. Students also have the option to do work-based learning, which can mean internships, a youth apprenticeship or working at high-end simulated job sites inside the school.

“This creates not just a pipeline to jobs but also to career choices,” said Jeff Stenroos, the district’s director of CTE and alternative education.

Related: A lot goes on in classrooms from kindergarten to high school. Keep up with our free weekly newsletter on K-12 education.

“There are a lot of really good-paying jobs in this area. Students don’t need to leave, or go earn a four-year degree,” Stenroos said. An auto mechanic can “earn six figures by the age of 26 and that’s more than an educator with a master’s degree,” he said.

Beloit’s effort is a shift in high school emphasis similar to the extensive CTE programs being run in other places, notably Indiana, Kentucky and Alabama. In 2024, 40 states enacted 152 CTE-related policies, the biggest push in five years, according to Advance CTE, a nonprofit group that represents state CTE officials. Nationwide, about 20 percent of high school students take a concentration of CTE courses, it says, adding that the high school graduation rate for students who concentrate in CTE is 90 percent, 15 percentage points higher than the national average.

Three years ago, Wisconsin called for 7 percent of its high school students to be in workplace learning programs by 2026. Beloit’s progress puts it far ahead of that target. In Beloit Memorial, nearly 1 in 3 students meet this designation today, Stenroos said.

The high school features a cavernous construction area where students build full-scale rooms, learn masonry and complete plumbing and electrical wiring projects. The metal shop offers 16 welding stations and a die-cutter machine that allows students to create customized pieces to fit projects. Down the street, the school runs an eight-bay car repair center, a space it took over when a Sears autobody shop left town.

These spaces are “better than a lot of technical colleges,” Stenroos said.

In addition to their high school courses, Beloit Memorial students pile up industry-recognized certifications, Stenroos said. More than 40 percent of its students graduate with at least one certification, and 1 in 4 of them has multiple certifications.

Related: Schools push career ed classes for all, even kids heading to college

While some simple certifications, such as OSHA Workplace Safety, can be accomplished in just 10 hours, others, such as those for the American Welding Society, require up to 500 hours of student work, he added. The state has called for 9 percent of graduating high school students to have earned at least one certification by next year. To incentivize schools to offer these opportunities, the state’s Department of Workforce Development pays schools for each student who earns a certification; in 2024, Beloit received $85,000 through this program, Stenroos said.

One of the school’s best automotive students, Geiry Lopez, graduated this year with five Automotive Service Excellence certifications. Standing less than 5 feet tall, Lopez said she is not bothered that she might not look like a typical mechanic. “I know I can do this,” she said, adding that she hopes to work on heavy machinery such as tractor trailers after she graduates.

She’s worked on her own car, with some fellow students, replacing the brakes, a front axle, rotors and wheel bearings at the school’s garage, she said, although she still hasn’t been able to drive it.

“My dad is taking forever to teach me how to drive,” she said.

The garage operates like an actual business, but the only customers are teachers and other Beloit staffers and students. Students estimate work costs, order parts and communicate with customers before any repairs take place. While oil changes and brake replacements are common, some students are totally rebuilding an engine in one car.

Over in the welding room, rising senior Cole Mellom was putting the finishing touches on a smoker he built in less than a month’s time. He said he loved the creativity of finding a plan, cutting the metal and building something that he could sell, all while in school. Plus, he knows that welding is a key skill needed for his dream job, race-car fabrication.

In the past, students created a custom-made protective plate that the city’s police use on a bomb squad vehicle.

The welding program has 125 students this year and had to turn away 65 more because of space limitations, Stenroos said; last year, 17 of the school’s welding academy graduates enlisted in the armed forces to specialize in welding.

These programs are designed to help meet the future needs of the state’s workforce. More than one-third of Wisconsin jobs will require education beyond high school but less than a bachelor’s degree by 2031, according to the Association for Career and Technical Education. For the last four years, the state has had more job openings than people on unemployment.

“There’s more jobs than there are people to fill them right now,” said Deb Prowse, a former career academy coach at Beloit Memorial who now works at Craftsman with Character, an area nonprofit that helps train students for careers in skilled trades.

Hooker, the Lloyd’s Plumbing HVAC manager, agreed. “Every project we work on has a delay, from a multimillion-dollar mansion to a three-bedroom spec,” he said. “There aren’t enough workers.”

The main reason Beloit Memorial has been able to zoom past state and national goals for both CTE and work-based learning is the school’s single-minded focus since 2018 on helping to ensure that its graduates will understand what businesses need and giving them a head start toward gaining those skills.

High school officials actually pared back the program from 44 pathways to 13, Stenroos said, part of an effort to tie each pathway to specific jobs. About 75 percent of pathways target area jobs, with the remaining quarter highlighting prominent professions within the state, he added.

Even though three straight budget referendum defeats have left the district with a $6.2 million funding gap, Stenroos said he’s been able to keep the CTE equipment modernized through donations and strategic allocation of the school’s federal Perkins grant and the state reimbursement for student certifications. In one instance, the school recently bought a $20,000 scanner for its automotive program; the machine can not only help diagnose a car problem, but also connect students to garages throughout the country that have successfully fixed the specified problem.

“It’s an expensive piece of equipment,” Stenroos said, “but it’s industry-certified and will give students real-life experience.”

Each of the three academies has an advisory board of teachers and industry professionals who work out how to embed practical lessons in classroom curriculum. “We ask business people, ‘What do you need, and how can we help our kids get there?’” said Stenroos.

Related: A new kind of high school diploma trades chemistry for carpentry

“It’s really cool how receptive the school is to feedback,” said Heather Dobson, the business development manager at Corporate Contractors, Inc., a 200-person general contracting firm.

She explained that the district has incorporated small changes over the years, such as having students work in Microsoft programs instead of Google Classroom apps and teaching them how to write a professional email.

“Rarely is there an idea presented that they don’t embrace,” said Celestino Ruffini, the CEO of Visit Beloit, a nonprofit that promotes tourism of the city. The school is expanding its hospitality program because of the expected influx of jobs connected to the new casino and hotel, he said.

All the changes aren’t at the high school, however. In order to employ Beloit Memorial students, Frito-Lay had to alter its corporate policy of not allowing anyone under 18 to work in its plants, according to Angela Slagle, a supply chain manager there. The company now hires Beloit Memorial students for its career exploration youth apprenticeship program, she added.

The connection to area businesses goes beyond the school’s leaders. Each year, about 10 teachers complete an externship in which they spend one week of their summer at a local business. Teachers are paid $1,000 for the 20 hours, and they not only learn about what jobs a company may have but also find ways to incorporate real-world problems into their classroom lessons.

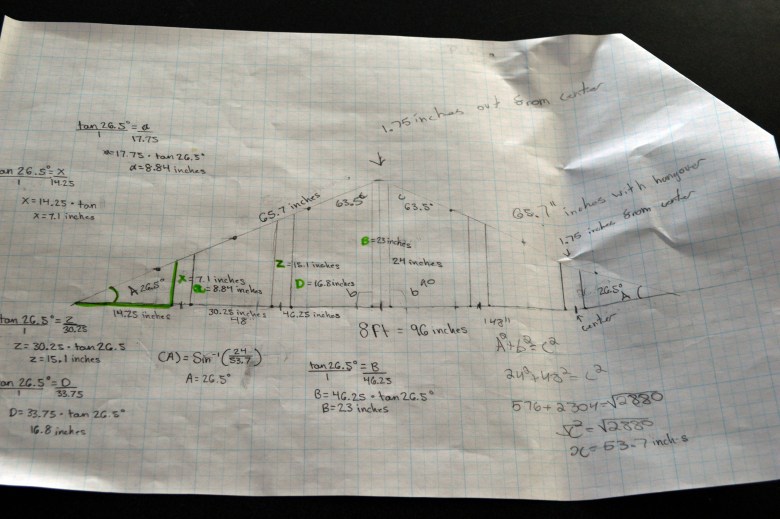

A few summers back, math teacher Michelle Kelly spent a week at Corporate Contractors. She was searching for different ways to use construction-based math problems with her students. In addition to using math to estimate a bid for a project or calculate the surface area of a job, she realized that complex math is needed to build a truss, the framework used to support a roof or bridge.

Because the triangular truss is supported by different lengths of wood inside its structure, Kelly said, building one requires the calculation of angles, total area, how much wood is needed and more. Since all her algebra students were in the school’s construction academy, she partnered with those teachers to go beyond blueprints and have the 10th graders build trusses, a collection of which sit in the back of her classroom.

She sees this work as one way to help counter the chronic absenteeism that has existed since Covid. Teaching with this kind of hands-on work makes students see the relevance of algebra, she said. “Would it be easier to just have them take a test? Yes.”

Beloit Memorial Principal Emily Pelz said the school’s work is paying off. In the last four years, the school’s four-year graduation rate has ticked up slightly, from 83.4 percent in 2021-22 to 85.2 percent in 2024-25, while its attendance went from 78.5 percent to 84.8 percent in the same period, Pelz said.

Related: ‘Golden ticket to job security’: Trade union partnerships hold promise for high school students

Rik Thomas, a rising senior who already has his own business repairing and modifying cars, said this work has definitely made him more interested in school. While he thought the academy would merely explain what a construction career might include, “It’s nice to find out how to do the work.” His father works in construction and, Thomas added, “He loves that I take this program.”

Thomas and his classmates built a wooden shed earlier this year and were able to sell it for $2,500, with the money going to pay for more materials. Likewise, the first smoker created in the welding class was bought by Stenroos; the students are looking forward to posting the second one for sale after they determine how much they should charge.

While the school’s construction and other trade-related fields have drawn the most attention, its three academies also offer career paths in healthcare, education, business, the arts, hospitality and more.

For example, rising senior Tayvon Cates said he hopes to study pre-med at a historically Black college or university on his way to becoming a cardiology radiologist. Cates, who is in the school’s health and education academy, said, “If you want to do something, the school can help you do it.”

This story about career and technical education was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.