As we witness a fundamental shift in the American economy, the question facing parents and educators is no longer simply “Should my child go to college?” but rather “How do we prepare young people to thrive in a rapidly transforming workforce?” The answer lies in early intervention – building executive functioning skills, identifying areas of strength, and cultivating the confidence and competencies that will serve students throughout their lives, regardless of the path they choose.

A Manufacturing Renaissance and What It Means for Our Students

Economist Nancy Lazar recently highlighted a transformation that’s been quietly unfolding for over a decade. As she explained, “This is transformational. It has actually been unfolding for about 15 years. It started last cycle, when capital spending started to come back to the United States… we started to get goods-producing jobs increased. 2010 through 2019.”

This shift represents more than just economics – it’s a fundamental reimagining of what career success looks like. Lazar emphasized the multiplier effect of manufacturing jobs: “When you create factories, you need a support system around it. Other smaller factories, distribution centers, and then other services eventually, eventually unfold.”

For our students, this means opportunity. But only if we prepare them properly.

The Skills Gap Isn’t Insurmountable – It’s a Training Challenge

One of the most encouraging aspects of Lazar’s analysis is her pragmatic view of the “skills gap.” When asked whether skills mismatches would create friction in this economic transformation, her response was refreshingly direct:

“I visited a prison about 6 years ago, where they were training inmates as they got parole in skills. And they would train them, and they’d go out […] and they would get a job. So you can train people to work in factories. I grew up in a factory town. I saw it myself, and it’s training.”

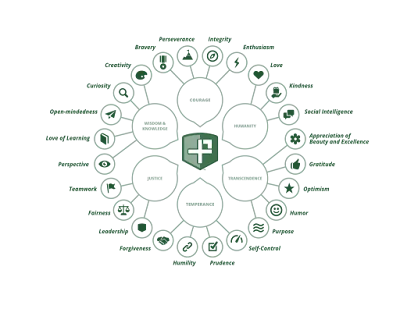

This is where executive functioning skills become critical. The ability to plan, organize, manage time, regulate emotions, and adapt to new situations – these are the foundations that make any training successful. Students who develop strong executive function early don’t just learn specific skills; they learn how to learn, how to persist through challenges, and how to present themselves as valuable contributors.

Rethinking the College Paradigm

Lazar’s interview included a striking moment when discussing Palantir’s hiring practices: “Palantir was in the news last week. They’re hiring high school kids. Great idea. Get a job, then see if you want to go, go to college, if you need to go, if you need to go to college.”

Let’s be clear: this isn’t an anti-college message. It’s a pro-purpose message.

College remains an invaluable experience for many students – particularly those pursuing fields that require specific credentials or advanced study. The college environment can foster character development, expose students to the humanities and sciences that broaden perspective, and provide the space for young adults to discover who they are and what they value. These are legitimate and important outcomes.

However, when college costs approach $400,000-$500,000 for a four-year degree at a private institution, we must ask hard questions. If the primary goal is character building and general education, a $24,000 per year public university can accomplish that beautifully. If the goal is career preparation without a specific professional credential requirement, technical training may be more appropriate and cost-effective.

The issue isn’t whether college has value – it does. The issue is whether the value received justifies the investment made, and whether we’re honest about what we’re purchasing.

The Dignity and Promise of Technical Education

Lazar put it plainly: “I do think this is transformational, is healthy for the economy, not everybody needs to go to college, wants to go to college, and there should be other job opportunities.”

The data supports this transformation. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, median wages for skilled trades have increased significantly over the past decade. Electricians now earn a median salary of approximately $60,000 annually, with experienced professionals in specialized areas earning well over $80,000. Similarly, HVAC technicians, plumbers, and manufacturing technicians are seeing wage growth that outpaces inflation, with many positions offering comprehensive benefits and job security.

A 2023 report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce found that 30% of workers with associate degrees earn more than the median bachelor’s degree holder. In fields like industrial machinery mechanics, respiratory therapy, and radiation therapy, two-year degree holders often out-earn four-year college graduates.

These aren’t consolation prizes – they’re dignified, skilled professions that offer security, growth, and the satisfaction of tangible, meaningful work.

Lazar emphasized the importance of community colleges and training partnerships: “Community college system, companies working with community colleges. I’m excited about it, rather than people depending upon the government, where they can actually go out and get a healthy, good job.”

This is where we, as educators and parents, must examine our own biases. Have we unconsciously communicated that technical careers are somehow “less than”? Have we steered capable students away from hands-on work that might actually suit their strengths and interests better than a traditional academic path?

Early Intervention: Building the Foundation for Any Path

This is why our work at Novella Prep focuses so heavily on executive functioning skills, confidence building, and identifying individual strengths early in a student’s educational journey. Whether a student ultimately pursues:

- A four-year university degree

- Technical certification

- Community college training

- Apprenticeship programs

- Entrepreneurship

- Direct workforce entry

…they will need the same core competencies:

Organization and Planning: The ability to manage complex projects, meet deadlines, and coordinate multiple responsibilities.

Self-Regulation: Managing frustration, persisting through difficulty, and maintaining focus in the face of distractions.

Metacognition: Understanding how they learn best, identifying when they need help, and continuously improving their approach.

Communication: Presenting ideas clearly, collaborating with others, and advocating for themselves appropriately.

Adaptability: Adjusting to new environments, learning new systems, and remaining flexible as circumstances change.

These skills aren’t taught in a single semester. They’re developed over years, through consistent practice, reflection, and coaching. The earlier we begin, the more deeply embedded these capacities become.

Aligning Education with Purpose

Here’s what we should be asking our middle and high school students:

- What activities make you lose track of time because you’re so engaged?

- What problems in the world bother you enough that you want to help solve them?

- What skills do you already have that others find valuable?

- What kind of work environment appeals to you – collaborative or independent, physical or sedentary, creative or systematic?

And then, critically: What preparation path will best develop your strengths while addressing your growth areas, at a cost that makes sense for your goals?

For some students, that will absolutely mean a selective four-year university. For others, it might mean starting at community college and transferring. For still others, it might mean a technical certification earned while working, allowing them to enter the workforce without debt while building real-world experience.

The Role of Executive Function in Workforce Value

Lazar noted that “80% of jobs are created in companies with less than 500 employees,” and emphasized the importance of small business growth. In smaller organizations, employees often wear multiple hats and must demonstrate initiative, problem-solving, and reliability from day one.

These are executive function skills in action. An employee who can:

- Anticipate needs before being asked

- Organize their work efficiently

- Communicate proactively about challenges

- Adapt when priorities shift

- Take ownership of outcomes

…will always be valuable, regardless of their specific technical training or degree credentials.

This is why we emphasize these skills alongside academic content. We’re not just preparing students for college admission; we’re preparing them to be the kind of people others want to work with, hire, and promote.

Confidence Built on Competence

Perhaps most importantly, early executive function training builds genuine confidence. Not the hollow self-esteem of participation trophies, but the real thing – confidence rooted in demonstrated competence.

When students experience themselves as capable – when they successfully plan and execute a complex project, when they overcome a genuine challenge through persistence, when they see tangible results from their efforts – they internalize a sense of agency that serves them forever.

This confidence allows them to:

- Try new things without fear of failure

- Advocate for themselves in educational and work settings

- Recover from setbacks without catastrophizing

- Make decisions aligned with their values rather than others’ expectations

A Practical Path Forward

For parents and educators reading this, here are concrete steps:

- Start Early: Executive function skills develop most rapidly before age 25. Don’t wait until junior year of high school to address organization, time management, and self-regulation challenges.

- Identify Strengths: Help students discover what they’re genuinely good at and interested in. Resist the urge to push them toward paths that seem prestigious but don’t fit their actual abilities and interests.

- Explore All Options: Visit technical schools and community colleges with the same care you’d visit four-year universities. Talk to people working in trades and technical fields. Challenge assumptions about what constitutes “success.”

- Run the Numbers: If a four-year private college costs $400,000+, be explicit about the return on investment. What specific outcomes justify that expense? If the answer is primarily “experience” and “education,” consider whether those outcomes could be achieved at lower cost.

- Prioritize Skills Over Credentials: Focus on building competencies that transfer across contexts – executive function, communication, critical thinking, technical literacy. These matter more than the name on the diploma.

- Embrace Multiple Pathways: Success isn’t linear. Many people benefit from working before college, or combining work and school, or pursuing technical training first and academic credentials later. There’s no single “right” way.

Conclusion: Preparation for Purpose

Nancy Lazar concluded her interview by expressing excitement about the economic transformation: “I’m excited about it, rather than people depending upon the government, where they can actually go out and get a healthy, good job.”

That should be our goal for every student: a healthy, good job – or better yet, fulfilling work that leverages their strengths, provides economic security, and contributes value to others.

Getting there requires more than test scores and GPAs. Life requires executive functioning skills, self-awareness, confidence built on competence, and the wisdom to choose a path aligned with individual strengths and goals rather than generic prestige.

At Novella Prep, this is the work we’re committed to – helping students develop not just the skills to get into college, but the capacities to thrive in whatever path they choose. Because in a transforming economy, the most valuable credential isn’t a diploma. It’s the ability to learn, adapt, contribute, and grow throughout a lifetime.

Dr. Tony Di Giacomo is an educational expert specializing in executive function development and college preparation. Through Novella Prep, his company works with students and families to build the skills, confidence, and strategic thinking necessary for long-term success.