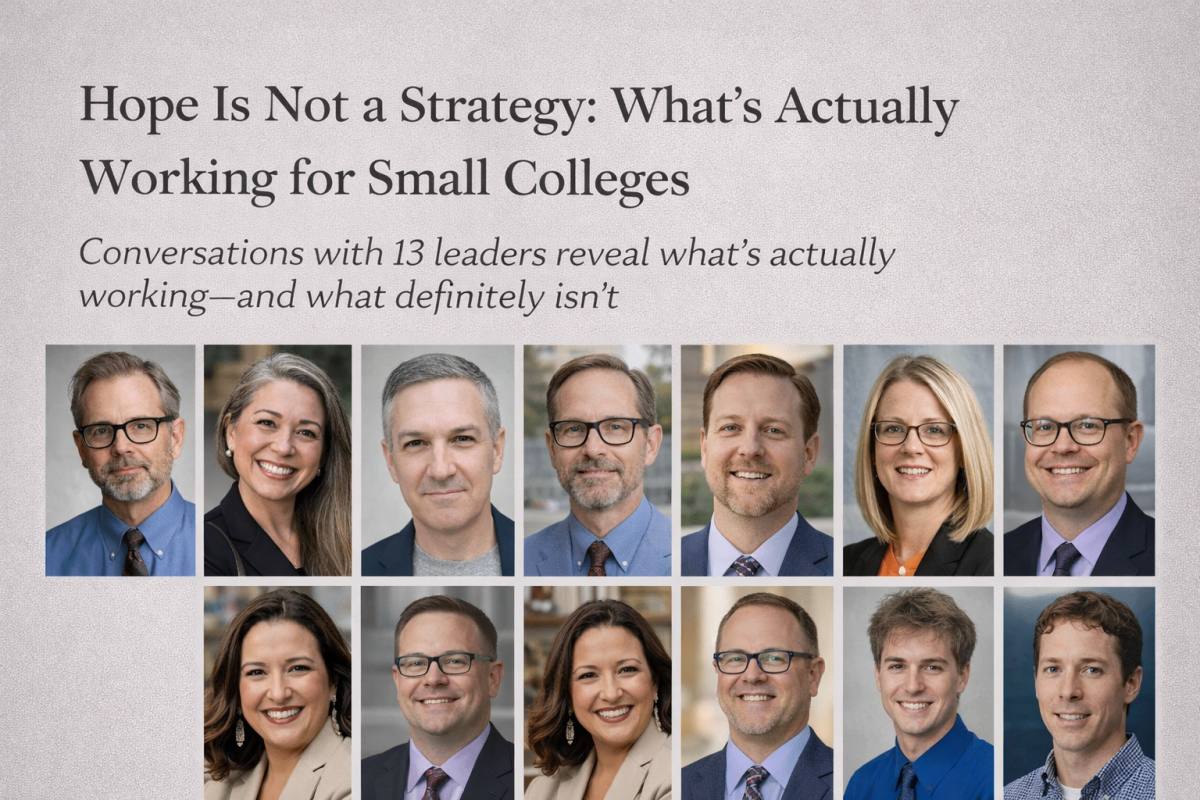

Editor’s Note By Dean Hoke: This winter, Small College America completed its most ambitious season yet—13 conversations with presidents, consultants, and association leaders who are navigating the most turbulent period in higher education history. What emerged wasn’t theory or wishful thinking. It was a working playbook of what’s actually succeeding on the ground. This article synthesizes the five insights that matter most.

When Hope Meets Reality

Jeff Selingo doesn’t mince words.

“Hope is not a strategy,” he said bluntly in Season 3 of Small College America.

Jeff Selingo, a Best Selling Author and higher education advisor, named what every small college leader knows but hates to admit: the old playbook is dead. The demographic cliff isn’t coming—it’s here. Traditional enrollment models are broken. And no amount of wishful thinking about “riding out the storm” will change that.

But here’s what surprised me across 13 conversations this season: nobody was sugarcoating reality, yet the conversations weren’t depressing.

They were energizing.

From Frank Shushok describing how Roanoke College built a K-12 lab school that creates a pipeline from kindergarten forward, to Teresa Parrott explaining why Grinnell took over a failing daycare center instead of issuing a mission statement about community engagement, from Gary Daynes doubling down on Salem College’s women’s mission when conventional wisdom said to go co-ed, to Kristen Soares navigating 2,500 California bills every legislative session—Season 3 captured something rare.

Leaders who have moved past denial and into action.

What emerged wasn’t abstract strategy consulting. It was concrete, operational intelligence from people doing the work. Here are the five insights that separate institutions that will thrive from those that won’t.

1. Stop Marketing, Start Building Pipelines

The traditional enrollment model—recruit high school seniors, get them to visit campus, send them glossy viewbooks, hope they choose you over 47 other colleges—is dead. Small colleges know this. But most are still acting like better marketing will solve it.

It won’t.

As Selingo pointed out, “At some point you have to come up with another segment of students if you’re tuition dependent because there just aren’t enough of those students to go around.”

Translation: You cannot market your way out of a demographic crisis.

The institutions seeing results aren’t the ones with slicker viewbooks or better social media strategies. They’re the ones building actual infrastructure for new student populations.

What does that look like in practice?

At Roanoke College, President Frank Shushok has approached enrollment not as a marketing problem, but as a pipeline design problem.

Roanoke’s lab school creates a K–12 pathway while simultaneously solving a community need. Students who attend the lab school encounter the college early, come to trust it, and see it as part of their educational journey long before senior year. That’s not recruitment—that’s ecosystem building.

The same logic shows up in Roanoke’s employer partnerships. The T-Mite Scholars program flips the traditional internship model: students complete two internships, receive a guaranteed job interview upon graduation, and receive tuition support from the employer. That’s not workforce development with a side of enrollment. That’s workforce development with enrollment as the byproduct.

This pipeline mindset also appears at scale in California, as described by Kristen Soares, President of the Association of Independent California Colleges and Universities. California’s Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT) program creates guaranteed, transparent pathways from community colleges into four-year institutions—no credit games, no hidden requirements, no “we’ll evaluate your transcript and get back to you.” Just clear bridges that actually work for the students who need them most.

Notice what these examples have in common: they aren’t marketing campaigns. They are operational partnerships designed to reduce friction and create consistent flows of students.

As Shushok observed, “I think what you’re starting to see is some incredibly creative, adaptive, and agile institutions—because it requires a level of courage and resilience and tenacity.”

The bottom line is straightforward: if your enrollment strategy is still primarily marketing-driven, you’re playing the wrong game. Build infrastructure. Create pipelines. Solve real community problems.

The students will follow.

2. Is Your Mission Statement Hurting You

Teresa Parrott, Principal TVP Communications dropped what might be the most important insight of the entire season: small colleges need to shift “from mission to impact.”

What she means matters right now.

Most small college websites lead with mission statements like “We develop well-rounded citizens who think critically and serve their communities.”

It’s lovely. It’s inspiring to people who already work at the college. And it’s entirely unpersuasive to everyone else.

Legislators don’t care about your mission. Prospective students’ parents don’t care about your mission. Community members wondering why they should support you don’t care about your mission.

They care about what you actually do.

Compare generic mission language to Grinnell College’s approach. When their town’s daycare center was failing, Grinnell didn’t release a statement about their commitment to the community. They took over the daycare center. When the community golf course struggled, they stepped in to sustain it.

As Parrott put it, “They are so embedded in their community that they really are almost a second arm of the government.”

That’s not rhetoric. That’s concrete, documentable community impact.

Or take Gary Daynes, President of Salem College insight about resource sharing at Salem: “It makes zero cents to build a football field. Seems like you could share with the local high school.”

Simple. Obvious. Rarely done.

But when colleges actually do it—by sharing theaters, athletic facilities, cultural resources, and programming—they become infrastructure their communities can’t imagine losing. They become politically and economically essential.

The shift is this: Stop leading with what you believe. Start leading with what you do.

Not “We believe in service.” Try “We trained 45% of the nurses in this region.”

Not “We value community.” Try “We operate the only daycare center in town.”

Not “We develop leaders.” Try “Our graduates run 23 local businesses and employ 400 people.”

The institutions sufficiently community-embedded to make these claims are politically protected. The ones still leading with inspirational language become vulnerable the moment budgets get tight.

The takeaway: Your communications team shouldn’t be writing mission statements. They should be documenting measurable community impact and leading with it everywhere.

3. Lean Into What Makes You Different

Selingo said it most directly: “There is more differentiation in higher education than we care to admit, but the presidents haven’t leaned into that enough.”

Translation: You’re already different. You’re just afraid to say it loudly.

Daynes decided to reaffirm its commitment to educating girls and women. That’s not chasing the market—it’s the opposite. But Daynes explained they looked at their data and realized the women’s college identity was a strength, not a liability they needed to downplay.

Faith-based institutions are deepening their religious identities rather than treating them as mere historical affiliations that make the college vaguely Methodist or nominally Catholic.

Health-focused campuses are building employer pipelines instead of trying to be liberal arts generalists who happen to have a nursing program.

The pattern is clear: institutions trying to be less distinctive are struggling. Institutions doubling down on what makes them unique are finding traction.

But here’s the critical part Daynes emphasized: distinctiveness has to be operational, not just marketing.

If you’re a “community-engaged college,” you need actual programs embedded in the community—shared facilities, pipeline programs, workforce partnerships—not just a tagline on your website.

If you’re “career-focused,” you need employer partnerships with real job placement data and students who can point to specific outcomes.

If you’re faith-based, that identity needs to shape curriculum, student life, residential programs, and institutional decisions in ways students and families can see and experience.

When distinctiveness is only branding, students and families see through it immediately. When it’s operational, it becomes your competitive advantage.

The takeaway: Generic positioning is a slow death. Find what makes you genuinely different, operationalize it across your institution, and communicate it relentlessly.

4. Real Partnerships vs. Press Releases

Shushok nailed the mindset shift small colleges need to make: “Partnerships are everything in this moment. And once you get past that you’re competing with any of these entities, you start to realize, no, these are partners.”

K-12 schools. Community colleges. Employers. Local governments. Hospitals. These aren’t competitors or nice-to-haves anymore. They’re essential infrastructure for institutional survival.

But Daynes offered the crucial warning: “It’s easy to sign MOUs. It’s harder to sustain them.”

Read that again.

Translation: Your partnership announcements don’t mean anything.

What matters is actual student flow. What matters is shared staffing. What matters is programs that operate year after year, not photo ops at signing ceremonies where everyone shakes hands and nobody follows through.

Ask yourself right now: Do you know how many students transferred in from your community college “partners” last year? Do you have dedicated staff managing those relationships, or is it an extra duty for someone already overwhelmed?

If you don’t know those numbers or don’t have dedicated staff, you don’t have partnerships. You have press releases.

The partnerships that work have dedicated staffing to manage relationships and smooth student transitions, clear metrics measuring student flow rather than signed agreements, operational integration where partner institutions actually share resources, and financial skin in the game from all parties.

Roanoke’s “Directed Tech” program with Virginia Tech counts the senior year as both undergraduate completion and the first year of a master’s degree. That’s not a partnership; that’s structural integration that changes the economics and value proposition for students.

California’s ecosystem, where UC, CSU, community colleges, and independent institutions work together on workforce development, isn’t an inspirational collaboration story. It’s an economic necessity backed by 2,500+ pieces of legislation every two years, as Soares noted.

When the state is writing hundreds of bills requiring coordination, you can’t fake it with a handshake and a press release.

The bottom line: Count your partnerships that produce actual student flow and resource sharing. If that number is zero or close to it, stop announcing new partnerships and start making the ones you have actually work.

5. Liberal Arts is Workforce Development (Stop Being Defensive About It)

The false choice between liberal arts and workforce preparation came up in nearly every conversation. And every single guest rejected it.

Shushok’s framing was the clearest: “Technical skills get you the first job. Human capacity skills enable 15 career reinventions.”

Think about that.

In a world where AI can write code, analyze data, generate reports, and automate technical tasks, what becomes more valuable—technical skills that become obsolete in five years, or the ability to adapt, think critically, communicate clearly, work across differences, and solve novel problems?

As Shushok put it, “We might find that the liberal arts, the humanities, the small colleges, if we allow ourselves to be shaped by this moment, are exactly what the doctor ordered for the 21st century.”

The problem: small colleges are still communicating defensively about the liberal arts instead of offensively.

Stop saying “The liberal arts are ALSO important for careers.”

Start saying, “The liberal arts are the ONLY preparation for a 40-year career in an unpredictable economy.”

Stop apologizing for not being pre-professional.

Start explaining why pre-professional education is increasingly obsolete in an age of AI and constant technological disruption.

And most importantly: build the bridges so students can actually see the connection.

That means boards that understand finance, politics, and operations—not just fundraising. CFO leadership that addresses structural challenges honestly. Political engagement that mobilizes entire institutions, not just government relations staff. And communications teams that function as impact documenters, not mission statement writers.

Kristen Soares noted that 92% of California’s clinical workforce is trained at private colleges. That’s not despite the liberal arts foundation—it’s because of it.

Nurses need critical thinking to make life-and-death decisions in ambiguous situations.

Mental health counselors need empathy and adaptability to serve diverse communities.

Teachers need communication skills and the ability to think on their feet.

The liberal arts aren’t tangential to workforce needs. They’re central. But you have to stop defending them and start operationalizing the connection in ways students, families, and employers can see.

The takeaway: The liberal arts are perfectly suited for workforce needs. Stop defending. Start operationalizing. Build the bridges.

So what do you actually DO with all this?

Season 3 didn’t just surface problems—it revealed a working playbook. Here’s what leaders who are successfully navigating this moment have in common:

- They’re building infrastructure for new student populations instead.

- They’re documenting measurable community impact and leading with it.

- They’re deepening what makes them genuinely distinctive.

- They’re measuring student flow and resource sharing.

- They’re operationalizing the connection to careers.

Shushok’s insight about “recalibration versus balance” might be the most critical leadership lesson of the season. As he put it, “Balance is not a destination, but constant recalibration.”

Small college leadership today isn’t about finding the right strategy and executing it for five years. It’s about continuous adjustment based on what’s actually working.

That means:

• Boards that understand finance, politics, and operations—not just fundraising

• CFO leadership that addresses structural challenges honestly

• Political engagement that mobilizes entire institutions, not just government relations staff

• Communications teams that function as impact documenters, not mission statement writers

As Daynes reflected, “I love small colleges. There are folks of intense gifts amongst the faculty and staff who have chosen to be the places that they are.”

That’s the source of optimism throughout Season 3.

Not naive hope that things will get better on their own.

But grounded confidence in devoted people willing to do hard, creative work.

Jeff Selingo’s blunt assessment—”Hope is not a strategy”—wasn’t meant to demoralize. It was meant to liberate.

Small colleges that thrive in the next decade will be the ones that:

• Build operational infrastructure for new student populations

• Document and communicate measurable community impact

• Operationalize distinctiveness throughout the institution

• Create partnerships that produce actual student flow

• Connect liberal arts to career outcomes without defensiveness

• Recalibrate constantly based on what’s working

The leaders in Season 3 aren’t waiting for permission or hoping for a miracle. They’re building lab schools. They’re taking over daycare centers. They’re sharing facilities with high schools. They’re creating guaranteed pathways to graduate programs. They’re documenting their impact and leading with it.

They’re doing the work.

And they’re proving that hope—real, grounded hope based on action rather than wishful thinking—comes from building things that work.

Looking Forward: Three Conversations to Start This Week

If you’re a president, provost, trustee, or senior leader, here are three conversations you can start right now if you haven’t already done so :

1. With your enrollment team: Ask them to map every actual pipeline you have for new students—not marketing campaigns, but structural pathways that produce consistent student flow. If the list is short or non-existent, that’s your answer. Start building infrastructure, not marketing plans.

2. With your communications team: Ask them to document your measurable community impact in the last 12 months. Not what you believe or aspire to do—what you actually did. How many jobs did you create? How many nurses did you train? What facilities do you share? What problems did you solve? If the answer is vague or mission-statement-heavy, you have work to do.

3. With your board: Present them with a simple question: “If we could only communicate three things about our institution to prospective students, legislators, and community members, what would they be?” If the answers are about mission and values rather than concrete impact and distinctive programs, you need to shift the conversation.

These aren’t theoretical exercises. They’re diagnostic tools that reveal whether your institution is still operating from the old playbook or building the new one.

Selingo was right: hope is not a strategy. But action, infrastructure, partnerships, impact, and constant recalibration is a playbook that works.

—

Season 3 of Small College America featured conversations with 13 leaders in the field of higher education. Thanks to everyone who participated, and especially my co-host Kent Barnds and my Producer and lovely wife Nancy Hoke.

- Raj Bellani, Chief of Staff, Denison College

- Gary Daynes, President, Salem College

- Josh Hibbard, Vice President of Enrollment Management, Whitworth University

- Dean McCurdy, President, Colby Sawyer College

- Jon Nichols, Faculty member and author

- Teresa Parrott, Principal TVP Communications

- Karen Petersen, President, Hendrix College

- Michael Scarlett, Professor of Education, Augustana College

- Jeff Selingo, Best Selling Author and higher education advisor

- Frank Shushok, President, Roanoke College

- Kristen Soares, President, Association of Independent California Colleges and Universities

- Gregor Thuswaldner, Provost, La Roche University

- Jeremiah Williams, Professor of Physics, Wittenberg University

The conversations continue.

Small College America returns in February with a new season featuring candid discussions with presidents, faculty, and leaders navigating the most consequential moment in higher education.

Hosted by Dean Hoke and Kent Barnds, the series explores the evolving role of small colleges, their impact on communities, and the strategies leaders are using to adapt and endure.

Listen or watch past episodes on Apple, Spotify, YouTube, and many others, or preview what’s coming next, and follow the series at www.smallcollegeamerica.net.