by Kathryn Joyce, The Hechinger Report

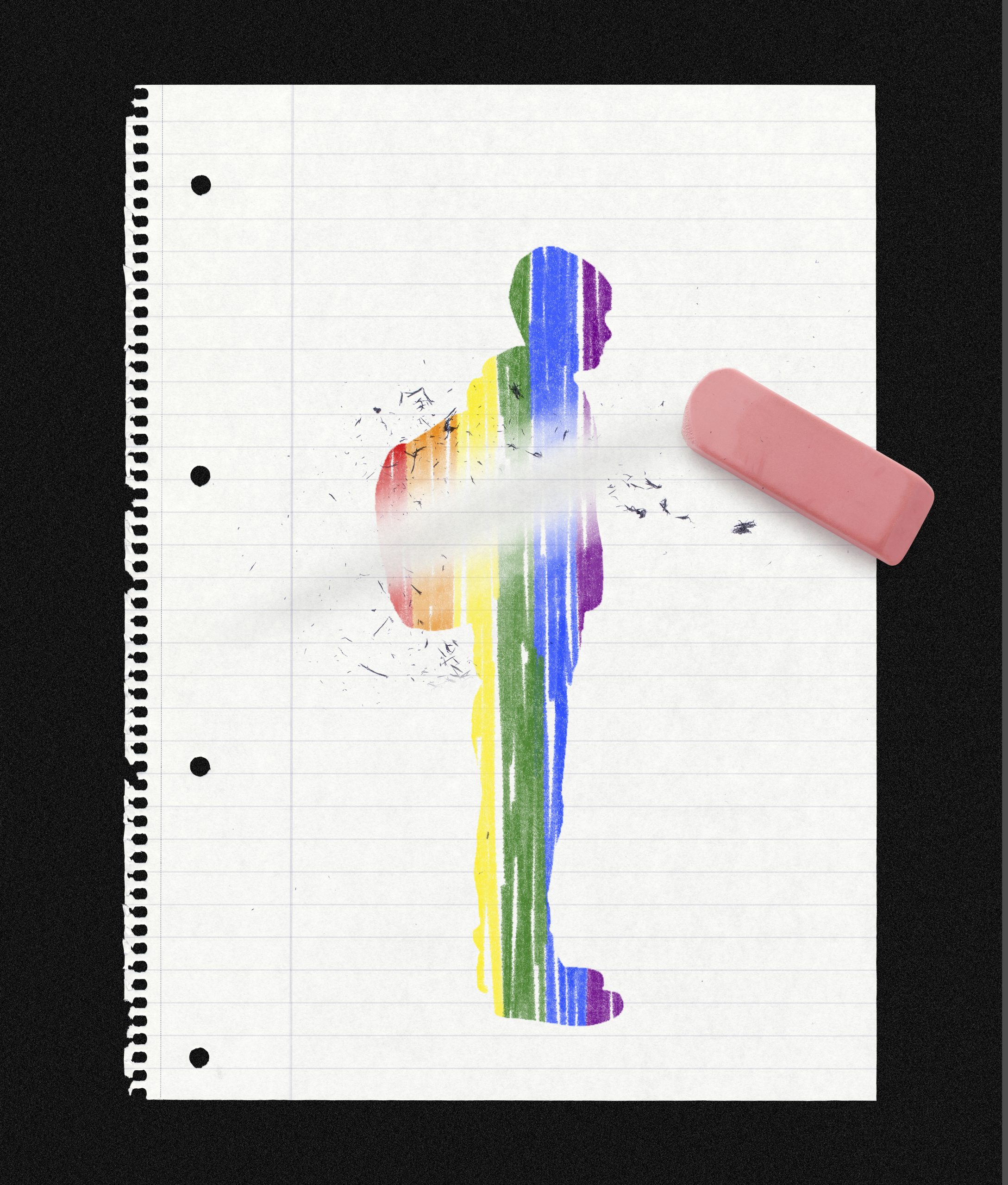

January 6, 2026

The West Shore school board policy committee meeting came to a halt almost as soon as it began. As a board member started going over the agenda on July 17, local parent Danielle Gross rose to object to a last-minute addition she said hadn’t been on the district’s website the day before.

By posting notice of the proposal so close to the meeting, charged Gross, who is also a partner at a communications and advocacy firm that works on state education policy, the board had violated Pennsylvania’s open meetings law, failing to provide the public at least 24 hours’ notice about a topic “this board knows is of great concern for many community members interested in the rights of our LGBTQ students.”

The committee chair, relentlessly banging her gavel, adjourned the meeting to a nonpublic “executive session.” When the committee reconvened, the policy was not mentioned again until the meeting’s end, when a lone public commenter, Heather Keller, invoked “Hamlet” to warn that something was rotten in the Harrisburg suburbs.

The proposed policy, which would bar trans students from using bathrooms and locker rooms aligned with their gender identity, was a nearly verbatim copy of one crafted by a group called the Independence Law Center — a Harrisburg-based Christian right legal advocacy group whose model policies have led to costly lawsuits in districts around the state.

“Being concerned about that, I remembered that we don’t partner with the Independence Law Center,” Keller said. “We haven’t hired them as consultants. And they’re not our district solicitor.”

To those who’d followed education politics in the state, Keller’s comment would register as wry understatement. Over the past several years, ILC’s growing entanglement with dozens of Pennsylvania school boards has become a high-profile controversy. Through interviews, an extensive review of local reporting and public documents, In These Times and The Hechinger Report found that, of the state’s 500 school districts, at least 20 are known to have consulted with or signed formal contracts accepting ILC’s pro bono legal services — to advise on, draft and defend district policies, free of charge.*

But over the last year, it’s become clear ILC’s influence stretches beyond such formal partnerships, as school districts from Bucks County (outside Philadelphia) to Beaver County (west of Pittsburgh) have proposed or adopted virtually identical anti-LGBTQ and book ban policies that originated with ILC — sometimes without acknowledging any connection to the group or where the policies came from.

In districts without formal partnerships with ILC, such as West Shore, figuring out what, exactly, their board’s relationship is to the group has been a painfully assembled puzzle, thanks to school board obstruction, blocked open records requests and reports of backdoor dealing.

Although ILC has existed for nearly 20 years, its recent prominence began around 2021 with a surge of “parents’ rights” complaints about pandemic-era masking, teaching about racism, LGBTQ representation and how library books and curricula are selected. In many districts where such debates raged, calls to hire ILC soon followed.

In 2024 alone, ILC made inroads of one kind or another with roughly a dozen districts in central Pennsylvania, including West Shore, which proposed contracting ILC that March and invited the group to speak to the board in a closed-door meeting the public couldn’t attend. (ILC did not respond to multiple interview requests or emailed questions.)

On the night of that March meeting, Gross organized a rally outside the school board building, drawing roughly 100 residents to protest, even as it snowed. The board backed down from hiring ILC, but that didn’t stop it from introducing ILC policies. In addition to the proposed bathroom policy, that May the board passed a ban on trans students joining girls’ athletics teams after they’ve started puberty and allowed district officials to request doctors’ notes and birth certificates to enforce it.

To Gross, it’s an example of how West Shore and other school boards without formal relationships with ILC have still found ways to advance the group’s agenda. “They’re waiting for other school boards to do all the controversial stuff with the ILC,” Gross said, then “taking the policies other districts have, running them through their solicitors, and implementing them that way.” (A spokesperson for West Shore stated that the district had not contracted with ILC and declined further comment.)

“It’s like a hydra effect,” said Kait Linton of the grassroots community group Public Education Advocates of Lancaster. “They’ve planted seeds for a vine, and now the vine’s taking off in all the directions it wants to go.”

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

ILC was founded in the wake of a Pennsylvania lawsuit that drew nationwide attention and prompted significant local embarrassment.

In October 2004, the Dover Area School District — situated, like West Shore, in York County, south of Harrisburg — changed its biology curriculum to introduce the quasi-creationist theory of “intelligent design” as an alternative to evolution. Eleven families sued, arguing that intelligent design was “fundamentally a religious proposition rather than a scientific one.” In December 2005, a federal court agreed, ruling that public schools teaching the theory violated the U.S. Constitution’s establishment clause.

During the case, an attorney named Randall Wenger unsuccessfully tried to add the creationist Christian think tank he worked for — which published the book Dover sought to teach — to the suit as a defendant, and, failing that, filed an amicus brief instead. When the district lost and was ultimately left with $1 million in legal fees, Wenger found a lesson in it for conservatives moving forward.

Speaking at a 2005 conference hosted by the Pennsylvania Family Institute — part of a national network of state-level “family councils” tied to the heavyweight Christian right organizations Family Research Council and Focus on the Family — Wenger suggested Dover could have avoided or won legal challenges if officials hadn’t mentioned their religious motivations during public school board meetings.

“Give us a call before you do something controversial like that,” Wenger said, according to LancasterOnline. Then, in a line that’s become infamous among ILC’s critics, Wenger invoked a biblical reference to add, “I think we need to do a better job at being clever as serpents.” (Wenger did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

The following year, in 2006, the Pennsylvania Family Institute launched ILC with Wenger as its chief counsel, a role he remains in today, in addition to serving as chief operating officer. ILC now has three other staff attorneys and has worked directly as plaintiff’s attorneys on two Supreme Court cases: one was part of the larger Hobby Lobby decision, which allows employers to opt out of employee health insurance plans that include contraception coverage; the other expanded religious exemptions for workers.

ILC has financial ties and a history of collaborating with Christian right legal advocacy behemoth Alliance Defending Freedom, including on a 2017 lawsuit against a school district outside Philadelphia that allowed a trans student to use the locker room aligned with their gender. ILC has filed amicus briefs in support of numerous other Christian right causes, including two that led to major Supreme Court victories for the right in 2025: Mahmoud v. Taylor, which limited public schools’ ability to assign books with LGBTQ themes; and United States v. Skrmetti, which affirmed a Tennessee ban on gender-affirming care for minors. In recent months, the group filed two separate amicus briefs on behalf of Pennsylvania school board members in anti-trans cases in other states. In both cases, which were brought by Alliance Defending Freedom and concern school sports and pronoun usage, ILC urged the Supreme Court to “resolve the issue nationwide.”

In lower courts, ILC has worked on or contributed briefs to lawsuits seeking to start public school board meetings with prayer and to allow religious groups to proselytize public school students, among other issues. More quietly, as the local blog Lancaster Examiner reported — and as one ILC attorney recounted at a conference in 2022 — ILC has defended “conversion therapy,” the broadly discredited theory that homosexuality is a disorder that can be cured.

To critics, all of these efforts have helped systematically chip away at civil rights protections for LGBTQ students at the local level, seeding the policies that President Donald Trump’s administration is now trying to make ubiquitous through executive orders. And while local backlash is building in some areas, activists are hindered by the threat that the ILC’s efforts are ultimately aimed at laying the groundwork for a Supreme Court case that could formalize discrimination against transgender students into law nationwide.

But ILC’s greatest influence is arguably much closer to its Harrisburg home, in neighboring Lancaster and York counties, where nine districts have contracted ILC and at least three more have adopted its model policies.

-

The rural hillside and farmland in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, are seen on Aug. 15, 2025. The local school district, Penn Manor, adopted anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ policies presented by the Independence Law Center, a Harrisburg-based Christian-right legal advocacy group. -

A sign is seen in a residential neighborhood in Holtwood, Pennsylvania.

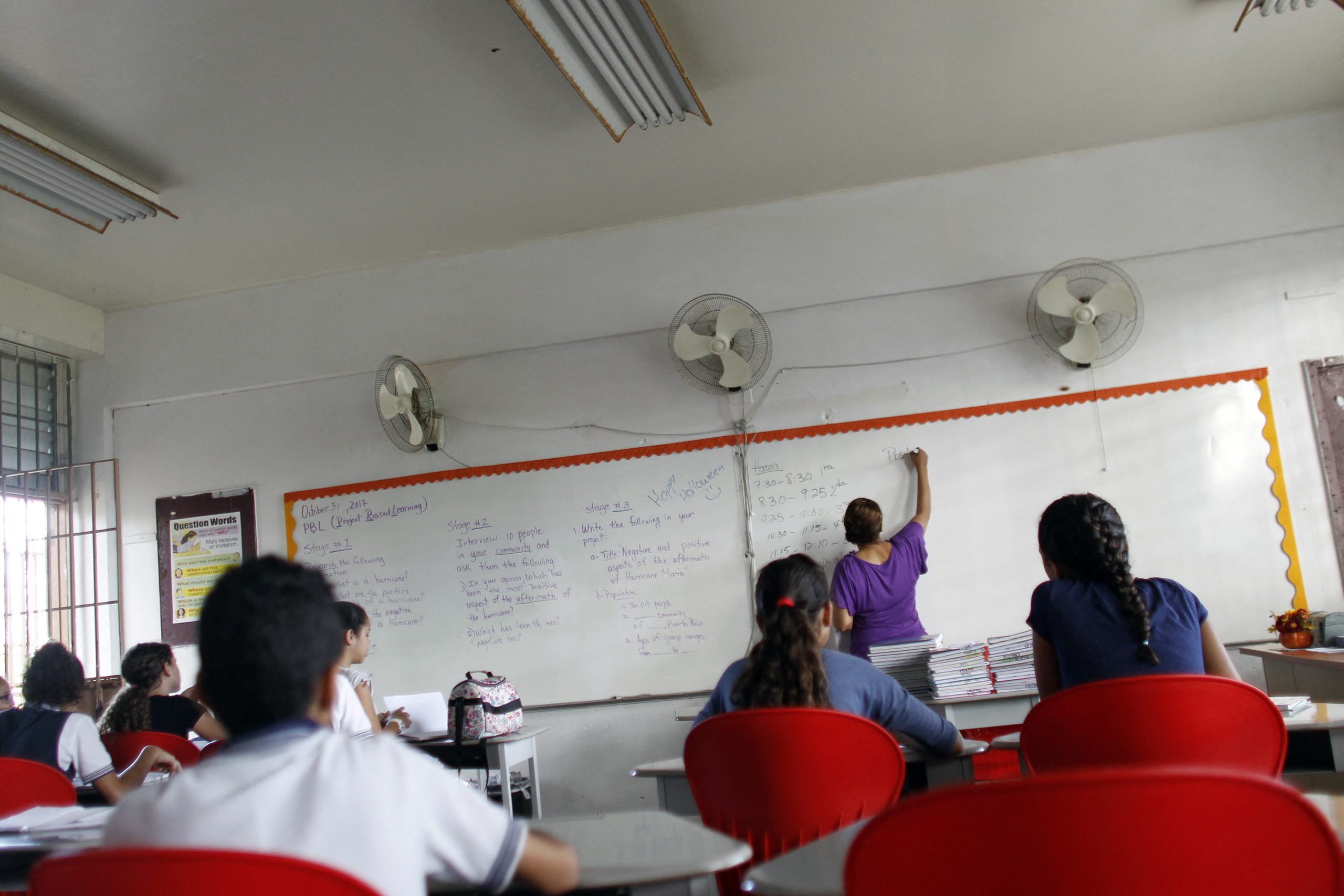

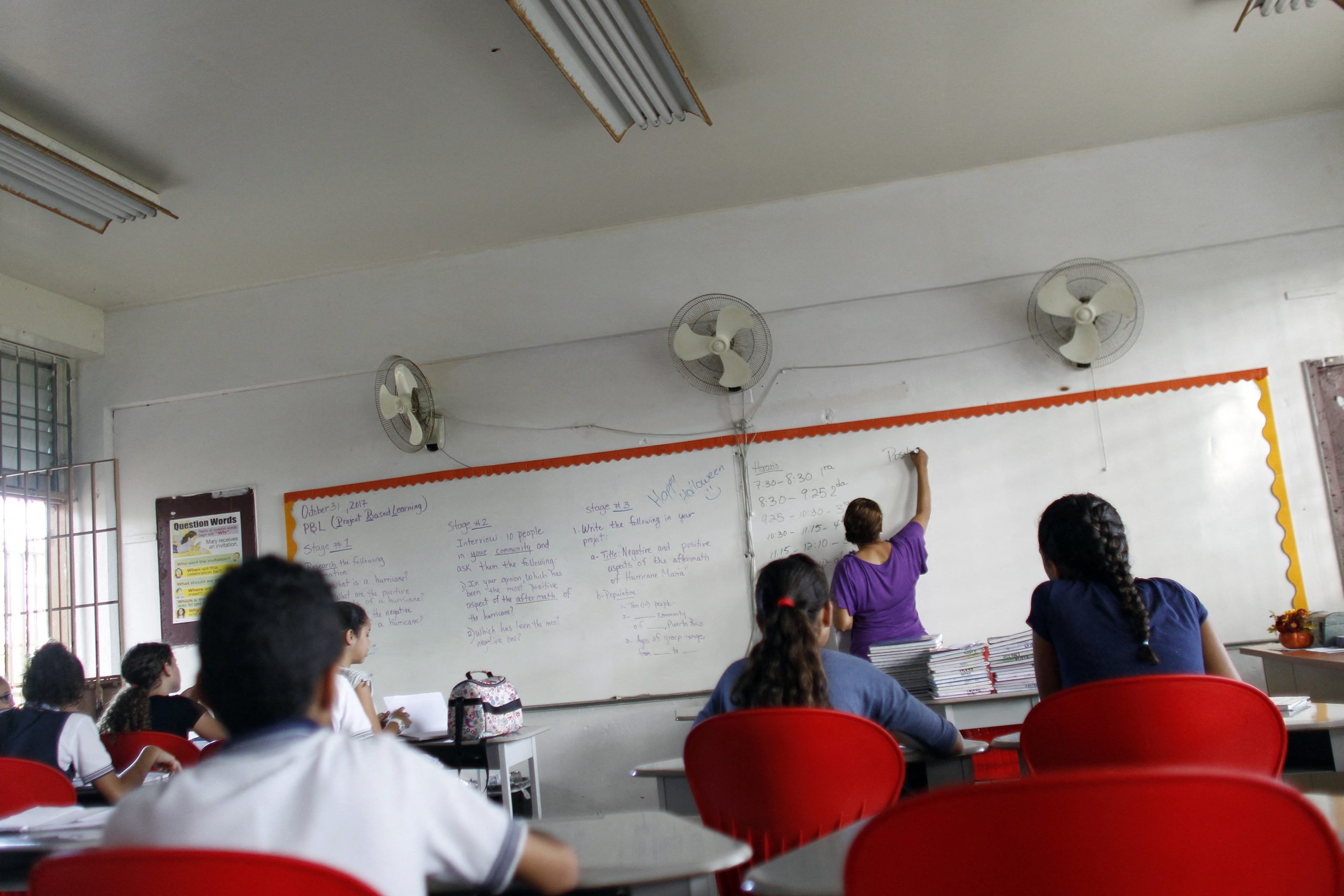

In Lancaster’s Hempfield district, it started with a 2021 controversy over a trans student joining the girls’ track team. School board meetings that had already grown tense over pandemic masking requirements erupted in new fights about LGBTQ rights and visibility. In the middle of one meeting, recalled Hempfield parent and substitute teacher Erin Small, a board member abruptly suggested hiring ILC to write a new district policy. The suddenness of the proposal caused such public outcry, said Small, that the vote to hire ILC had to be postponed.

But within a few months, the district signed a contract with ILC to write what became Pennsylvania’s first school district ban on trans students participating in sports teams aligned with their gender identity. Other ILC policy proposals followed, including a successful 2023 effort to bar the district from using books or materials that include sexual content, which immediately prompted an intensive review of books written by LGBTQ and non-white authors. (The Hempfield district did not respond to requests for comment.)

In nearby Elizabethtown, the path to hiring ILC began with a fraudulent 2021 complaint, when a man claimed, during a school board meeting, that his middle schooler had checked out an inappropriate book from the school library. Although it later emerged that the man had reportedly used a fake name and officials found no evidence he had children attending the school, his claim nonetheless sparked a long debate over book policies, which eventually led to the district contracting ILC as special legal counsel in 2024. Two anti-trans policies were subsequently passed in January 2025, and a ban on “sexually explicit” books, also based on ILC’s models, was discussed this past spring but has not moved forward to date. (The Elizabethtown district did not respond to requests for comment.)

Across the Susquehanna River in York County — where five districts have contracted ILC and two more have considered or passed its policies — the group’s influence has been broad and sometimes confounding. In one instance, as the York Dispatch discovered, ILC not only authored four policy proposals for the Red Lion Area School District, but ILC senior counsel Jeremy Samek, a registered Pennsylvania lobbyist, also drafted a speech for the board president to deliver in support of three anti-trans policies, all of which passed in 2024. (The Red Lion district did not respond to requests for comment.)

The same year, South Western School District, reportedly acting on ILC advice, ordered a high school to cut large windows into the walls of two bathrooms that had been designated as “gender identity restrooms,” allowing passersby in the hallway to see inside, consequently discouraging students from using them. (The district did not respond to requests for comment, but in a statement to local paper the Evening Sun, school board President Matt Gelazela cited student safety and said the windows helped staff monitor for vaping, bullying and other prohibited activities.)

In many districts, said Lancaster parent Eric Fisher, ILC’s growing relationships with school boards has been eased by the ubiquitous presence around the state of its sister organizations within the Pennsylvania Family Institute, including the institute’s lobbying arm, voucher group, youth leadership conference and Church Ambassador Network, which brings pastors from across Pennsylvania to lobby lawmakers in the state Capitol.

As a result, said Fisher, when ILC shows up in a district, board members often are already familiar with them or other institute affiliates, “having met them at church and having their churches put their stamp of endorsement on them. I think it makes it really easy for [board members] to say yes.”

But in nearly every district that has considered working with ILC, wide-scale pushback has also followed — though often to no avail. In June 2024, in Elizabethtown — where school board fights have been so fractious that they inspired a full-length documentary — members of the public spoke in opposition to hiring ILC at a ratio of roughly 5 to 1 before the board voted unanimously to hire the group anyway.

In the Upper Adams district in Biglerville, southwest of Harrisburg, the school board voted to contract ILC despite a cacophony of public comments and a 500-signature petition in opposition.

In Lancaster’s Warwick district, the school board’s vote to hire ILC prompted the resignation of a superintendent who had served in her role for 15 years and who reported that the district’s insurance carrier had warned the district might not be covered in future lawsuits if it adopted ILC’s anti-trans policies.

Since then, Warwick resident Kayla Cook noted during a public presentation about ILC this past summer, the mood in the district has grown grim. “We do not have any students at the moment trying to participate [in sports] who are trans. However, we have students who simply have a short haircut being profiled as being trans,” Cook said. “It’s tipped far into fear-based behaviors, where we are dipping our toes into checking the student’s body to make sure that they’re identifying as the appropriate gender.” (A district spokesperson directed interview requests to the school board, which did not respond to requests for comment.)

But perhaps nowhere was the fight as fraught as in Lancaster’s Penn Manor School District, which hired ILC to draft new policies about trans students just months after the suicide of a trans youth from Penn Manor — the fifth such suicide in the Lancaster community in less than two years.

Before the Penn Manor school board publicly proposed retaining ILC, in June 2024 — scheduling a presentation by and a vote on hiring ILC for the same meeting — district Superintendent Phil Gale wrote to the board about his misgivings. In an email obtained by LancasterOnline, Gale warned the board against policies “that will distinguish one group of students from another” and passed along a warning from the district’s insurance carrier that adopting potentially discriminatory policies might affect the district’s coverage if it were sued by students or staff.

In a narrow 5-4 vote, the all-Republican board declined to hire ILC that June. But after one board member reconsidered, the matter was placed back on the agenda for two meetings that August.

Members of the community publicly presented an open letter, signed by roughly 80 Penn Manor residents, requesting that, if policies about trans students were truly needed, the district establish a task force of local experts to draft them rather than outsource policymaking to ILC. One of the letter’s organizers, Mark Clatterbuck, a religious studies professor at New Jersey’s Montclair State University, said the district never acknowledged it or responded. (Maddie Long, a spokesperson for Penn Manor, said the district could not comment because of the litigation.)

That February, Clatterbuck’s son, Ash — a college junior and transgender man who’d grown up in Penn Manor — had died by suicide, shortly after the nationally publicized death of Nex Benedict, a nonbinary 16-year-old in Oklahoma who died by suicide the day after being beaten unconscious in a high school girls’ bathroom.

In the first August meeting to reconsider hiring ILC, Clatterbuck told the Penn Manor board, through tears, how “living in a hostile political environment that dehumanizes them at school, at home, at church and in the halls of Congress” was making “life unlivable for far too many of our trans children.”

Two weeks later, at the second meeting, Ash’s mother, Malinda Harnish Clatterbuck, pleaded for board members talking about student safety to consider the children these policies actively harm.

“ILC does not even recognize trans and gender-nonconforming children as existing,” said Harnish Clatterbuck, a pastor whose family has lived in Lancaster for 10 generations. “That fact alone should preclude them from even being considered by the board.”

-

A painted portrait of Ash Clatterbuck in his parents’ home in Holtwood, Pennsylvania. -

Malinda Harnish-Clatterbuck walks a labyrinth made in 2023 by her late son, Ash, on their property in Holtwood. -

Hand-painted signs that once hung on the walls of Ash’s dorm room

Her husband spoke again as well, telling the board how Ash had frequently warned about the spread of policies that stoke “irrational hysteria around” trans youth — “the kind of policies,” Mark Clatterbuck noted, “that the Pennsylvania-based Independence Law Center loves to draft.”

Reminding the board that five trans youth in the area had died by suicide within just 18 months, he continued, “Do not try to tell me that there is no connection between the kind of dehumanizing policies that the ILC drafts and the deaths of our trans children.”

But the board voted to hire ILC anyway, 5-4, and in the following months adopted two of ILC’s anti-trans policies.

Related: Red school boards in a blue state asked Trump for help — and got it

In anticipation of such public outcry, some school boards around Pennsylvania have taken steps to obscure their interest in ILC’s agenda.

Kristina Moon, a senior attorney at the Education Law Center of Pennsylvania, a legal services nonprofit that advocates for public school students’ rights, has watched a progression in how school boards interact with ILC.

When her group first began receiving calls related to ILC, around 2021, alarmed parents told similar stories of boards proposing book bans targeting queer or trans students’ perspectives, or identical packages of policies that included restrictions about bathrooms, sports and pronouns.

“At first, we would see boards openly talking about their interest in contracting with ILC,” said Moon. But as local opposition began to grow, “board members stopped sharing so publicly.”

Instead, Moon said, reports began to emerge of school boards discussing or meeting with ILC in secret.

In Hempfield, in 2022, the board moved some policy discussions into committee sessions less likely to be attended by the public, and held a vote on an anti-trans sports policy without announcing it publicly, possibly in violation of Pennsylvania’s Sunshine Act, as Mother Jones reported.

In Warwick, in 2024, several board members admitted meeting privately with ILC’s Randall Wenger, according to LancasterOnline.

Across the state, in Bucks County, one Central Bucks school board member recounted in an op-ed for the Bucks County Beacon how her conservative colleagues had stonewalled her when she asked about the origins of a new book ban policy in 2022, only to have the board later admit ILC had performed a legal review of it “pro bono,” as PhillyBurbs reported.

Subsequent reporting by the York Daily Record and Reuters revealed the board’s relationship with ILC was more involved and included discussions about other policies related to trans student athletes and pronoun policy. (Both Central Bucks’ books and anti-LGBTQ policies were later cited in an ACLU federal complaint that cost the district $1.75 million in legal fees, as well as in a related Education Department investigation into whether the district had created a hostile learning environment for LGBTQ students.)

But the sense of backroom dealing reached an almost cartoonish level in York County, where, in March 2024, conservative board members from 12 county school districts were invited to a secret meeting hosted by a right-wing political action committee, along with specific instructions about how to keep their participation off the public radar. According to the York Dispatch, the invitation came from former Central York school board member Veronica Gemma, who (after losing her seat) was hired as education director for PA Economic Growth, a PAC that had helped elect 48 conservatives to York school boards the previous fall. (Gemma did not respond to interview requests.)

Gemma’s invitation was accompanied by an agenda sent by the PAC, which included a discussion about ILC and how board members could “build a network of support” and “advance our shared goals more effectively countywide.” The invitation also included the admonition that “confidentiality is paramount” and that each district should only send four board members or fewer — to avoid the legal threshold for a quorum that would make the meeting a matter of public record.

“Remember, no more than 4 — sunshine laws,” Gemma wrote.

In the wake of stories like these, Wenger’s 2005 suggestion that conservatives “become as clever as serpents” in concealing their intentions became ubiquitous in coverage of and advocacy against ILC — showing up in newspaper articles, in editorials and even on a T-shirt for sale online.

“I think it’s very obvious,” reflected Moon, “but if something has to be taking place in secrecy, I’m not sure it can be good for our students.”

But the lack of transparency shows up in subtler ways too, in the spreading phenomenon of districts adopting ILC policies without admitting where the policies come from. That was the case in Eastern York in 2025, where board members who had previously lobbied for an ILC pronoun policy later directed their in-house attorney to write an original policy instead, following the same principles but avoiding the baggage an ILC connection would bring.

In Elizabethtown (which did contract ILC), one policy was even introduced erroneously referencing clauses from another district’s code, in an indication of how directly districts are copy-pasting from one another.

In 2025, ILC attorney Jeremy Samek even seemed to acknowledge the trend, predicting that fewer districts might contract ILC going forward, since the combination of Trump’s executive orders on trans students and the general spread of policies similar to ILC’s meant “it’s going to be a lot easier for other schools to do that without even talking to us.”

Related: Probes into racism in schools stall under Trump

In the face of what appears like a deliberate strategy of concealment, members of the public have increasingly turned to official channels to compel boards to disclose their dealings with ILC. Mark Clatterbuck did so in 2024 and 2025, filing 10 Right-to-Know requests with Penn Manor for all school board and administration communications with or about ILC and policies ILC consulted on and any records related to a set of specific keywords.

Thirty miles north, three Elizabethtown parents sued their school board in the spring of 2025, alleging it deliberately met and conferred with ILC in nonpublic meetings and private communications to “circumvent the requirements of the Sunshine Act.”

In both cases, and more broadly in the region, ILC critics are keenly aware that, by bringing complaints or lawsuits against the group or the school boards it works with, they might be doing exactly what ILC wants: furthering its chances to land another case before the Supreme Court, where a favorable ruling could set a dangerous national precedent, such as ruling that Title IX protections don’t cover trans students.

“They’re itching for a case,” said Clatterbuck. To that end, he added, his pro bono attorneys — at the law firm Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLC, which also represents the Elizabethtown plaintiffs pro bono — have been careful not to do ILC’s work for it.

Largely, that has meant keeping the cases narrowly focused on Sunshine Act violations.

But in both cases, there are also hints of the larger issue at hand — of whether, in a repeat of the old Dover “intelligent design” case, ILC’s policies represent school boards imposing inherently religious viewpoints on public schools. After all, ILC’s parent group, the Pennsylvania Family Institute, clearly states its mission is to make Pennsylvania “a place where God is honored” and to “strengthen families by restoring to public life the traditional, foundational principles and values essential for the well-being of society.” And in 2024, the institute’s president, Michael Geer, told a Christian TV audience that much of ILC’s work involves working with school boards “on the transgender issue, fighting that ideology that is pervasive in our society.”

In the Elizabethtown complaint, the plaintiffs argue that district residents must “have the opportunity to observe Board deliberations regarding policies that will affect their children in order to understand the Board members’ true motivation and rationale for adopting policies — particularly when policies are prepared by an outside organization seeking to advance a particular religious viewpoint and agenda.”

The public has ample cause to suspect as much. Five current and former members of Elizabethtown’s school board are connected to a far-right church in town, where the pastor joined 150 other locals in traveling to Washington, D.C., on Jan. 6, 2021. Among them were current board members Stephen Lindemuth — who once preached a sermon at the church arguing that “gender identity confusion” doesn’t “line up with what God desires” — and his wife, Danielle Lindemuth, who helped organize the caravan of buses that went to Washington. (Stephen Lindemuth replied by email, “I have no recollection of making any judgmental comments concerning LGBTQ in my most recent preaching the past few years.” Neither he nor his wife were accused of any unlawful acts on Jan. 6.)

Another board member until this past December, James Emery, went through the church’s pastoral training program and in 2022 served as a member of the security detail of far-right Christian nationalist gubernatorial candidate Doug Mastriano.

School board meetings in Elizabethtown have also frequently devolved into religious battles, with one local mother, Amy Karr, board chair of Elizabethtown’s Church of the Brethren, recalling how local right-wing activists accused ILC’s opponents of being possessed by demonic spirits or a “vehicle of Satan.”

In Penn Manor, Clatterbuck similarly hoped to lay bare the “overtly religious nature” of the board’s motivation by including in his Right-to-Know requests a demand for all school board communications about ILC policies containing keywords like “God,” “Christian,” “Jesus,” “faith” and “biblical.”

For nearly a year, the district sought to avoid fulfilling the requests, with questionable invocations of attorney-client privilege (including one board member’s claim that she had “personally” retained ILC as counsel), sending back obviously incomplete records and protestations that Clatterbuck’s keyword request turned up so many results that it was too burdensome to fulfill. Ultimately, Clatterbuck appealed to the Pennsylvania Office of Open Records to compel the board to honor the request.

This fall, Clatterbuck received a 457-page document from the board containing dozens of messages that suggest his suspicions were correct.

In response to local constituents writing in support of ILC — decrying pronoun policies as a violation of religious liberty, claiming “the whole LGBTQ spectrum is rooted in the brokenness of sin” and calling for board members to rebuke teachers unions in “the precious blood of Jesus” — at least three board members wrote back with encouragement and thanks. In one example, board member Anthony Lombardo told a constituent who had written a 12-page message arguing that queer theory is “inherently atheistic” that “I completely agree with your analysis and conclusions.”

When another community member sent the board an article from an evangelical website arguing that using “transgendered pronouns … falsifies the gospel” and “tramples on the blood of Christ,” board member Donna Wert responded, “Please know that I firmly agree with the beliefs held in [this article]. And please know that heightened movement is finally being made concerning this, as you will see.”

To Clatterbuck, such messages demonstrate the school board’s religious sympathies, as well as how Christian nationalism plays out at the local level. While national examples of Christian right dominance, like Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s Crusader tattoos or Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s “Appeal to Heaven” flag, get the most attention, Clatterbuck said, “this is what it looks like when you’re controlling local school boards and passing policies that affect people directly in their local community.”

But the local level might also be the place where advocates have the best chance of fighting back, said Kait Linton of Public Education Advocates of Lancaster.

Speaking ahead of a panel discussion on ILC at Elizabethtown’s Church of the Brethren last June — one of several panels PEAL hosted around Lancaster in the run-up to November’s school board elections — Linton emphasized the importance of focusing on the “hyperlocal.”

“With everything that’s happening at the national level,” Linton said, “we find a lot of folks get caught up in that, when really we have far less opportunity to make a difference up there than we do right here.”

PEAL’s efforts have been matched by other groups at the district level, like Elizabethtown’s Etown Common Sense 2.0, which local parent and former president Alisha Runkle said advocates against the sort of policies ILC drafts and also seeks to support teachers “being beaten down and needing support” in an environment of relentless hostility and demands to police their lesson plans, libraries and language.

They’re also reflected in the work of statewide coalitions like Pennsylvanians for Welcoming and Inclusive Schools, which helps districts share information about ILC policies — including a searchable map of ILC’s presence around the state — and resources like the Education Law Center, which has sent detailed demand or advocacy letters to numerous school districts considering adopting ILC-inspired policies.

This past November, that local-level work resulted in some signs for cautious hope. In Lancaster County’s Hempfield School District — one of the first districts in the state to hire ILC — the school board flipped to Democratic control. Among the new board members are Kait Linton and fellow PEAL activist Erin Small.

Across the river, in West Shore, the departure of three right-wing board members — one who resigned and two who lost their elections — left the board with a new 5-4 majority of Democratic and centrist Republican members. After the election, the board promptly moved to table three contentious policy proposals, including the anti-trans bathroom policy the board had copied from ILC and a book ban policy that drew heavily on ILC’s work.

While in other Lancaster districts — including Elizabethtown, Warwick and Penn Manor — school boards remained firmly in conservative control, there are also signs of growing pushback, as in Elizabethtown, where Runkle noted the teachers union has recently begun challenging the board during public meetings and local students have gotten active protesting book bans.

Similar trends have happened statewide, said the Education Law Center’s Kristina Moon, who noted that voters “were so concerned about the extremist action they saw on the boards that it was kind of a wake-up call: that we can’t sleep on school board elections, and we need to have boards that reflect a commitment to all of the students in our schools.”

While reports of ILC’s direct involvement with school boards seem to have waned in recent months, said Moon, that “does not mean the threat to our public schools is over. We see continued use of those discriminatory policies by school boards just copying the policy exactly as it was adopted elsewhere. And it causes the same harm in a district, whether the district is publicly meeting with ILC or not.”

Plus there are now Trump’s anti-trans executive orders, which have spread confusion statewide. And just this December, a legal challenge brought by another Christian right law firm, the Thomas More Society, is challenging the authority of Pennsylvania’s civil rights commission to apply anti-discrimination protections to trans students in public schools.

As a consequence, the Education Law Center has spent much of the past year trying to educate school and community leaders that executive orders are not the law itself, and they cannot supersede case law supporting the rights of LGBTQ students.

“We’re trying to cut through the noise,” Moon said, “to ensure that schools remain clear about their legal obligations to provide safe environments for all students … so they can focus on learning and not worrying about identity-based attacks.”

*Correction: At least 20 of Pennsylvania’s 500 school districts are known to have consulted with or signed formal contracts accepting the ILC’s pro bono legal services. This story previously reported 21.

Contact editor Caroline Preston at 212-870-8965, via Signal at CarolineP.83 or on email at [email protected].

This story about Independence Law Center was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, in partnership with In These Times. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter. Sign up for the In These Times weekly newsletter.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org/clever-as-serpents-how-a-legal-groups-anti-lgbtq-policies-took-root-in-school-districts-across-a-state/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org”>The Hechinger Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/hechingerreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/cropped-favicon.jpg?fit=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://hechingerreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=114185&ga4=G-03KPHXDF3H” style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://hechingerreport.org/clever-as-serpents-how-a-legal-groups-anti-lgbtq-policies-took-root-in-school-districts-across-a-state/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/hechingerreport.org/p.js”></script>