This story about high school speech and debate was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

DES MOINES, Iowa — Macon Smith stood in front of a nearly empty classroom 1,000 miles from home. He asked his opponent and the two judges in the room if they were ready to start, then he set a six-minute timer and took a deep breath.

“When tyranny becomes law, rebellion becomes duty,” he began.

In front of Macon, a 17-year-old high school junior, was a daunting task: to outline and defend the argument that violent revolution is a just response to political oppression.

In a few hours, Macon would stand in another classroom with new judges and a different opponent. He would break apart his entire argument and undo everything he had just said.

“An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind,” Macon started.

It doesn’t really matter what opinion Macon holds on violence or political oppression. In this moment in front of the judges, he believes what he’s saying. His job is to get the judges to believe with him.

Related: A lot goes on in classrooms from kindergarten to high school. Keep up with our free weekly newsletter on K-12 education.

Macon was one of more than 7,000 middle and high school students to compete in the National Speech and Debate Tournament this summer in Iowa, run by an organization that is celebrating a century in existence.

In that time, the National Speech and Debate Association has persevered through economic and social upheaval. It is entering its next era, one in which the very notion of engaging in informed and respectful debate seems impossible. The organizers of this event see the activity as even more important in a fracturing society.

“I don’t think there’s an activity in the world that develops empathy and listening skills like speech and debate,” said Scott Wunn, the organization’s president. “We’re continuing to create better citizens.”

Though the tournament is held in different cities around the country, for the 100th anniversary, the organizers chose to host it in Des Moines, where the association’s headquarters is based.

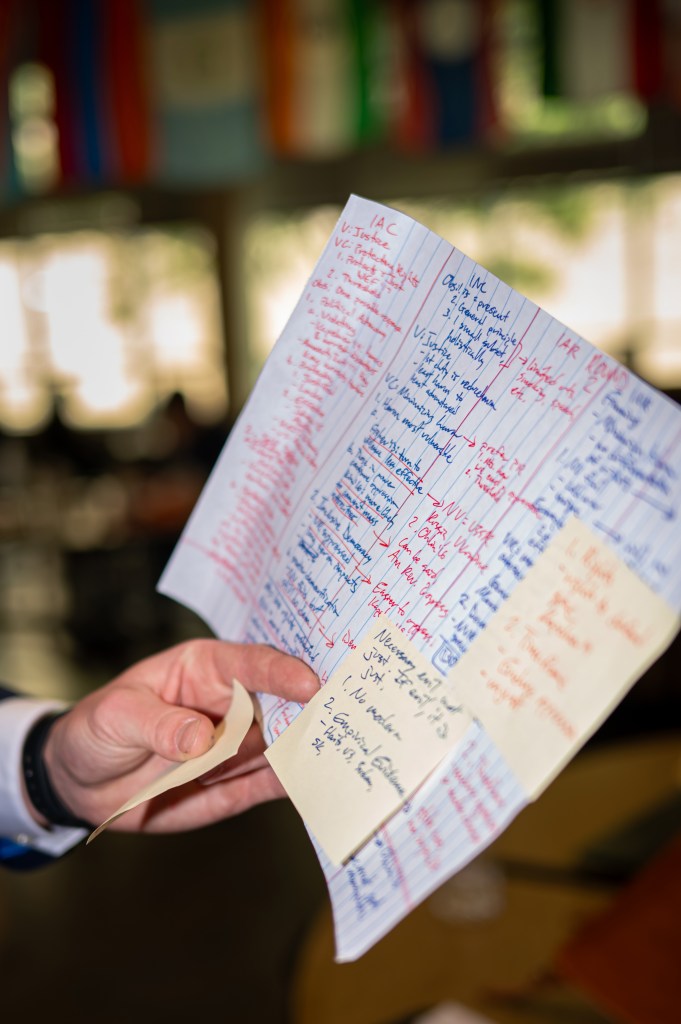

Preparing for this competition was a year in the making for Macon, who will be a senior at Bob Jones Academy, a Christian school in Greenville, South Carolina, this fall. Students here compete in more than two dozen categories, such as Original Oratory, in which they write and recite their own 10-minute speeches, or Big Questions, where they attempt to argue broad, philosophical ideas.

Macon’s specialty, the Lincoln-Douglas Debate, is modeled after a series of public, three-hour debates between Abraham Lincoln and Sen. Stephen Douglas in 1858. In this event, two students have just 40 minutes to set up their arguments, cross-examine each other and sway the judges.

“Even if I don’t personally believe it, I can still look at the facts and determine, OK, this is a good fact, or it’s true, and argue for that side,” Macon said.

Debaters often have to tackle topics that are difficult, controversial and timely: Students in 1927 debated whether there was a need for a federal Department of Education. In 1987, they argued about mandatory AIDS testing. In 2004, they debated whether the United States was losing the war on terror. This year, in the Public Forum division, students debated whether the benefits of presidential executive orders outweigh the harms.

Related: Teaching social studies in a polarized world

While the speech and debate students practiced for their national event, adults running the country screamed over each other during a congressional hearing on state sanctuary policies. A senator was thrown to the floor and handcuffed during a press conference on sending the National Guard to immigration enforcement protests in Los Angeles. Most Americans feel political discourse is moving in the wrong direction — both conservatives and progressives say talking politics with someone they disagree with has become increasingly stressful and frustrating.

Speech and debate club, though, is different.

“First of all, it gives a kid a place to speak out and have a voice,” said Gail Nicholas, who for 40 years has coached speech and debate at Bob Jones Academy alongside her husband, Chuck Nicholas, who is Macon’s coach. “But then also learn to talk to other people civilly, and I think that’s not what’s being modeled out there in the real world right now.”

On the second day of the competition in a school cafeteria in West Des Moines, Macon was anxiously refreshing the webpage that would show the results of his rounds to learn whether he would advance to semifinals.

For most of the school year, Macon spent two days a week practicing after school, researching and writing out his arguments. Like many competitors, he has found that it’s easy to make snap judgments when you don’t know much about an issue. Decisively defending that view, to yourself and to others, is much harder.

“I tend to go in with an opinion and lose my opinion as the topic goes on,” said Daphne DiFrancesco, a rising senior from Cary Academy in Cary, North Carolina.

Traveling for regional events throughout the school year means Macon has become friends with students who don’t always share his conservative views. He knows this because in debate, discussing politics and religion is almost unavoidable.

“It doesn’t make me uncomfortable at all,” Macon said. “You don’t want to burn down a bridge before you make it with other people. If you stop your connection with a person right at their political beliefs, you’re already cutting off half of the country. That’s not a good way to conduct yourself.”

Macon, and other students in the clubs, said participating has made them think more deeply about their own beliefs. Last year, Macon debated a bill that would defund Immigration and Customs Enforcement, an agency he supports. After listening to other students, he developed a more nuanced view of the organization.

“When you look at the principle of enforcing illegal immigration, that can still be upheld, but the agency that does so itself is flawed,” he said.

Related: ‘I can tell you don’t agree with me’:’ Colleges teach kids how to hear differing opinions

Henry Dieringer, a senior from L.C. Anderson High School in Austin, Texas, went into one competition thinking he would argue in favor of a bill that would provide work permits for immigrants, which he agrees with. Further research led him to oppose the idea of creating a federal database on immigrants.

“It made me think more about the way that public policy is so much more nuanced than what we believe,” Henry said.

On the afternoon of the second day of the national tournament, Macon learned he didn’t advance to the next round. What’s sad, he said, is he probably won’t have to think this hard about the justness of violent revolution ever again.

“There’s always next year,” Macon said.

Callista Martin, 16, a rising senior from Bainbridge High School in Washington state, also didn’t make the semifinals. Callista and Macon met online this year through speech and debate so they could scrimmage with someone they hadn’t practiced with before. It gave them the chance to debate someone with differing political views and argument styles.

“In the rounds, I’m an entirely different person. I’m pretty aggressive, my voice turns kind of mean,” Callista said. “But outside of the rounds, I always make sure to say hi to them before and after and say things I liked about their case, ask them about their school.”

Talking to her peers outside of rounds is perhaps the most important part of being in the club, Callista said. This summer, she will travel to meet with some of her closest friends, people she met at debate camps and tournaments in Washington.

Since Callista fell in love with speech and debate as a freshman, she has devoted herself to keeping it alive at her school. No teacher has volunteered to be a coach for the debate club, so the 16-year-old is coaching both her classmates and herself.

A lack of coaches is a common problem. Just under 3,800 public and private high schools and middle schools were members of the National Speech and Debate Association at the end of this past school year, just a fraction of the tens of thousands of secondary schools in the country. The organization would like to double its membership in the next five years.

That would mean recruiting more teachers to lead clubs, but neither educators nor schools are lining up to take on the responsibility, said David Yastremski, an English teacher at Ridge High School in New Jersey who has coached teams for about 30 years.

It’s a major time commitment for teachers to dedicate their evenings and weekends to the events with little supplemental pay or recognition. Also, it may seem like a risk to some teachers at a time when states such as Virginia and Louisiana have banned teachers from talking about what some call “divisive concepts,” to oversee a school activity where engaging with controversial topics is the point.

“I primarily teach and coach in a space where kids can still have those conversations,” Yastremski said. “I fear that in other parts of the country, that’s not the case.”

Related: A school district singled out by Trump says it teaches ‘whole truth history’

Dennis Philbert, a coach from Central High School in Newark, New Jersey, who had two students become finalists in the tournament’s Dramatic Interpretation category, said he fears for his profession because of the scrutiny educators are under. It takes the fun out of teaching, he said, but this club can reignite that passion.

“All of my assistant coaches are former members of my team,” Philbert said. “They love this activity [so much] that they came back to help younger students … to show that this is an activity that is needed.”

On the other side of Des Moines, Gagnado Diedhiou was competing in the Congressional Debate, a division of the tournament that mimics Congress and requires students to argue for or against bills modeled after current events. During one round, Gagnado spoke in favor of a bill to shift the country to use more nuclear energy, for a bill that would grant Puerto Rico statehood, and against legislation requiring hospitals to publicly post prices.

Just like in Congress, boys outnumbered girls in this classroom. Gagnado was the only Black teenager and the only student wearing a hijab. The senior, who just graduated from Eastside High School in Greenville, South Carolina, is accustomed to being in rooms where nobody looks like her — it’s part of the reason she joined Equality in Forensics, a national student-led debate organization that provides free resources to schools and students across the country.

“It kind of makes you have to walk on eggshells a little bit. Especially because when you’re the only person in that room who looks like you, it makes you a lot more obvious to the judges,” said Gagnado, who won regional Student of the Year for speech and debate in her South Carolina district this year. “You stand out, and not always in a good way.”

Camille Fernandez, a rising junior at West Broward High School in Florida, said the competitions she has participated in have been dominated by male students. One opponent called her a vulgar and sexist slur after their round was over. Camille is a member of a student-led group — called Outreach Debate — trying to bridge inequities in the clubs.

“A lot of people think that debate should stay the same way that it’s always been, where it’s kind of just — and this is my personal bias — a lot of white men winning,” Camille said. “A lot of people think that should be changed, me included.”

Despite the challenges, Gagnado said her time in debate club has made her realize she could have an influence in the world.

“With my three-minute speech, I can convince a whole chamber, I can convince a judge to vote for this bill. I can advocate and make a difference with some legislation,” said Gagnado, who is bound for Yale.

A day before the national tournament’s concluding ceremony, a 22-year-old attendee rushed the stage at the Iowa Event Center in Des Moines during the final round of the Humorous Interpretation speech competition, scaring everyone in the audience. After he bent down to open his backpack, 3,000 people in the auditorium fled for the exits. The man was later charged with possession of a controlled substance and disorderly conduct. For a brief moment, it seemed like the angry discourse and extreme politics from outside of the competition had become a part of it.

In response, the speech and debate organization shifted the time of some events, limited entrances into the building and brought in metal detectors, police officers and counselors. Some students, Gagnado among them, chose not to return to the event.

Still, thousands of attendees stayed until the end to celebrate the national champions. During the awards ceremony, where therapy dogs roamed the grounds, Angad Singh, a student from Bellarmine College Preparatory in California competing in Original Oratory, took the national prize for his speech on his Sikh identity and the phrase “thoughts and prayers” commonly repeated by American leaders after a tragedy, titled “Living on a Prayer.”

“I’ve prayed for change,” Singh told the audience. “Then I joined speech and debate to use my voice and fight for it.”

This story about high school speech and debate was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.