The report from The Education Trust examines state financial aid programs in Illinois, Indiana, and Minnesota, revealing that while some states are making progress, critical gaps remain in helping students who need assistance most.

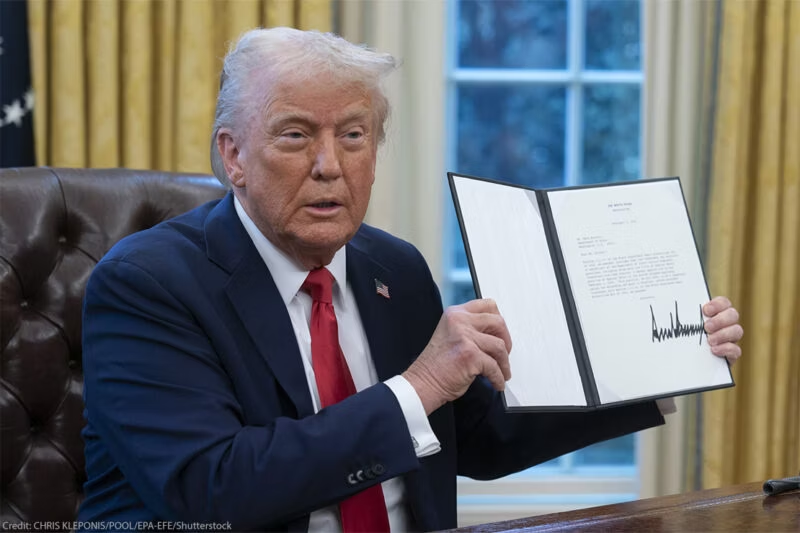

“The role of states in ensuring postsecondary access and affordability is essential now,” the report states, citing the Trump administration’s July Supreme Court victory allowing it to proceed with layoffs that cut the Department of Education’s staff in half.

The staffing cuts, which disproportionately targeted financial aid personnel, come as congressional Republicans passed legislation in July 2025 that restricted Pell Grant eligibility, limited parent borrowing, and made student loan repayment more expensive.

The report documents a stark affordability crisis. For recent high school graduates in Illinois, the average cost of attending a public four-year college represents 63.2% of annual family income for Black students, compared to 25.8% for white students.

In Indiana, the gap is similarly wide: 58.8% for Black families versus 22.1% for white families. Minnesota shows comparable disparities at 57.1% and 22.9%, respectively.

“Despite the benefits of a college degree, most families cannot cover the costs,” according to the report, which notes that the average cost of tuition, room, and board at public four-year colleges rose from $8,984 in 1980 to $22,389 in 2023, adjusted for inflation.

Meanwhile, the Pell Grant — the nation’s primary need-based aid — has lost purchasing power dramatically. In 1975, it covered more than 75% of college costs; today it covers only about one-third.

The Education Trust analysis found significant problems with how states allocate financial aid:

Illinois dedicates 98.8% of its undergraduate aid to need-based programs, primarily through its Monetary Award Program. However, the grant functions as “first dollar” aid, meaning other assistance must be applied to tuition before MAP funds, potentially leaving low-income students with little support for non-tuition costs.

Indiana splits funding more evenly: 40% goes to its need-based Frank O’Bannon Grant, while 44% supports combination need-and-merit programs like the 21st Century Scholars Program. The O’Bannon Grant provides larger awards to students at private colleges than public institutions — a policy that researchers say “privileges students from higher-income and higher-asset families.”

Minnesota allocates 72% of aid to its need-based State Grant program. The state recently launched the North Star Promise Scholarship, which provides tuition-free education to families earning under $80,000, though as a “last-dollar” program, it may provide minimal assistance to the lowest-income students already receiving Pell Grants.

The report identifies numerous eligibility requirements that exclude vulnerable students:

- Neither Indiana nor Minnesota provides aid to undocumented students, despite those residents paying state and local taxes

- None of the three states allow currently incarcerated students to receive aid, even though Congress restored Pell Grant eligibility for this population in 2023

- Minnesota excludes students in default on federal loans, making it harder for those experiencing financial hardship to complete degrees

- Part-time students — often working parents or adult learners — face reduced aid or exclusion in many programs

The Education Trust urges states to redesign financial aid systems with ten key features:

- Prioritize need-based aid over merit-based programs

- Cover costs beyond tuition, including housing, food, transportation, and childcare

- Serve part-time students, adult learners, and returning students

- Include undocumented and justice-impacted individuals

- Never convert grants to loans

- Serve students at all public colleges equally

- Allow access for those in loan default

- Consolidate programs into streamlined, need-based grants

- Use negative Student Aid Index numbers to direct more aid to the neediest

- Implement college access policies like direct admissions and FAFSA completion requirements

“What’s more, policies that promote college attendance are crucial for reducing barriers to higher education,” the report states, highlighting that both Illinois and Indiana have FAFSA completion requirements and direct admission programs, while all three states offer dual enrollment opportunities.

The report highlights the economic benefits of state investment in higher education. Each college graduate in Illinois increases the state’s annual GDP by approximately $155,566 and generates 6.8 jobs. The state recoups its education investment in just 4.1 years of the graduate’s working life.

Bachelor’s degree holders earn $1.2 million more over their lifetimes than those with only high school diplomas, are 24% more likely to be employed, and are nearly five times less likely to be incarcerated.

“State policymakers have a vested interest in ensuring that recent high school graduates pursue higher education and stay in state to complete their education,” the report concludes.

The analysis comes as education advocates warn that the federal retreat from college affordability could reverse decades of progress in expanding access to higher education, particularly for students of color and those from low-income backgrounds.