How interactive are your classroom activities? Do you have less energy for class than you used to? Do you find student grades declining? And are the teaching methods you’ve always relied on not working as well as they once did? We spoke to two college instructors, Chris Merlo (Professor of Computer Science at Nassau Community College) and Monika Semma (who holds a Master’s Degree in Cultural Studies and Critical Theory from McMaster University). Their strategies for interactive classroom activities will energize your class and get the discussion moving again.

Table of contents

- Why are interactive activities important?

- Assessment and evaluation

- 6 community-building activities

- 6 communication activities for college students

- Improve interactive learning with a flipped classroom

- 3 motivational activities for college students

- Project-based learning

- 6 team-building classroom activities for college students

- Interactive learning tools

- Interactive classroom activities, in short

- Frequently asked questions

Why are interactive classroom activities important?

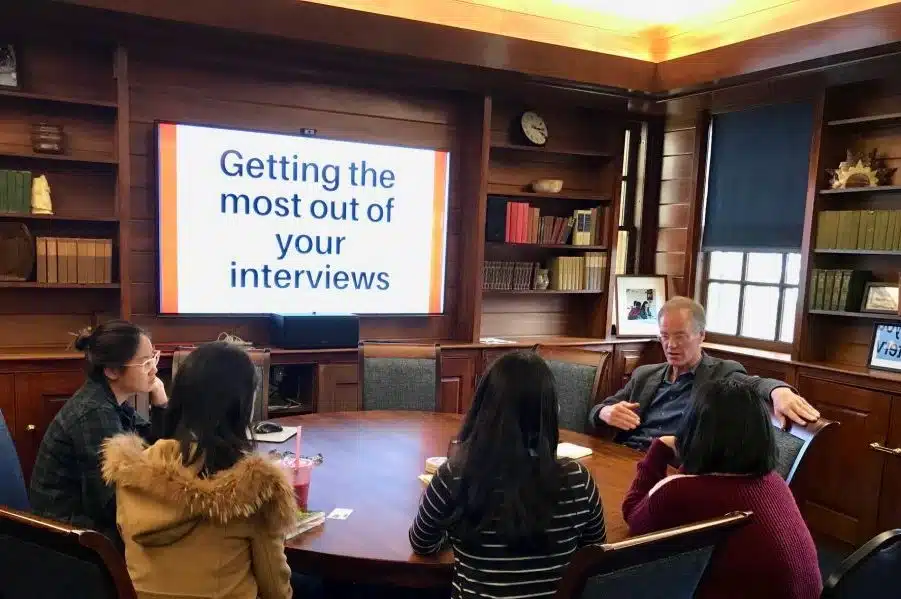

Merlo, a computer science teacher, says that interactive classroom activities are not new to students, and one main reason why teachers have trouble connecting is that they fail to adapt to their students’ perspectives. Interactive classroom activities are now widely used across different school settings, helping to engage students at all educational levels.

“My six-year-old son doesn’t find iPads amazing; to him, they’ve always just existed. Similarly, to a lot of students today, experiences like team exercises and flipped classrooms, while foreign to many instructors are not new.

“If we care about reaching today’s students, who seem to have a different idea of student responsibilities than we had, perhaps we have to reach them on their terms. Adapting teaching methods to include interactive teaching strategies can foster greater student engagement, participation, and long-term retention.

“In my thirties, I could still find a lot of similarities with my twenty-something students. But now, in my forties? Not so much. What I’ve started to realize is that it isn’t just the little things, like whether they’ve seen Ghostbusters. They haven’t. It’s the big things, like how they learn.”

Semma, a former humanities Teaching Assistant, found that the chalk-and-talk approach failed on her first day in front of a class. “It was a lot like parallel parking in front of 20 people,” she said. “I looked more like a classmate. I dropped the eraser on my face whilst trying to write my name on the board. One of my students called me ‘mom.’”

“I chalked it up to first day jitters, but that same quietness crept its way back into my classroom for the next tutorial, and the next tutorial and the next. While nearly silent in class, my students were rather vocal in the endless stream of emails that flooded my inbox. That way I knew they wanted to learn. I also knew that I had to find a way to make tutorials more engaging, such as using interactive activities to gauge the class’s knowledge and understanding.”From these experiences, Merlo and Semma now share some interactive classroom activities for students and for teachers that can turn a quiet classroom full of people unwilling to speak up to a hive of debate, making the student learning experience more collaborative for everyone. Many of these activities have been created to engage students in a fun way, and can be tailored to the specific content area or connected to today’s lesson. For example, case studies require students to analyze real-world scenarios to apply classroom concepts and foster critical thinking. Formative assessments, such as exit slips, encourage students to reflect on what they have learned today.

Energize your college classroom and get discussions flowing. Download The Best Classroom Activities for College Courses to engage and motivate students.

Assessment and evaluation

Assessment and evaluation are essential parts of the interactive classroom, helping teachers understand where students are in the learning process and how lesson plans might need to be adjusted. Instead of relying solely on traditional tests, teachers can use interactive classroom activities to assess student understanding in a fun and engaging way. For example, incorporating games, quizzes, or group discussions allows students to demonstrate their knowledge while staying actively involved in the lesson.

Teachers can also invite students to create their own assessments, such as writing practice test questions or designing a mini-quiz for their peers. This not only helps students review material but also gives them a sense of ownership over their learning. When students are involved in creating and evaluating content, they become more engaged and invested in the classroom experience. Interactive assessment methods, like peer review or collaborative games, make the learning process more dynamic and enjoyable for everyone. By weaving assessment and evaluation into interactive activities, teachers can create a classroom environment where students are motivated to participate and succeed.

6 community-building activities

1. Open-ended questions

Chris Merlo: Open-ended questions don’t take any planning. All they take is a class with at least one student who isn’t too shy. I remember a class a few semesters ago that started with nine students. Due to a couple of medical conditions and a job opportunity, three of the students had to drop the semester. The problem was that these three students were the ones I counted on to ask questions and keep the class lively! Once I was left with six introverted people, conversations during class seemed to stop.

By luck, I stumbled on something that got the students talking again. I said, “What has been the most difficult thing about [the project that was due soon]?” This opened the floodgates—students love to complain, especially about us and our demands. This one simple question led to twenty minutes of discussion involving all six students. Students share their thoughts and students discuss their perspectives with the entire class, making the activity engaging for everyone. I wasn’t even sure what a couple of these students’ voices sounded like, but once I gave them an open-ended opportunity to complain about an assignment, they were off to the races. A truly successful classroom activity.

2. What’s wrong with this example?

Chris Merlo: Students also love to find a professor’s mistakes—like me, I’m sure you’ve found this out the hard way. When I teach computer science, I will make up a program that, for instance, performs the wrong arithmetic, and have students find the bug. In a particularly quiet or disengaged class, you can incentivize students with five points on the next exam, or something similar. You can also reward the first student to find the correct answer, which encourages participation and adds a competitive element to the activity.

If you teach history, you might use flawed examples that change a key person’s name, such as “King Henry VIII (instead of King John) signed the Magna Carta in 1215,” or match a person to an incorrect event: “Gavrilo Princip is considered to have fired the first shot in the Spanish Civil War (instead of World War I).” Beam these examples on the whiteboard, and let the students’ competitiveness drive them to get the correct answer before their classmates.

3. Let students critique each other

Chris Merlo: This can go badly if you don’t set some ground rules for civility, but done well, classroom activities like this really help open up collaborative learning. One of my colleagues devised a great exercise: First, give students about half of their class time to write instructions that an imaginary robot can understand to draw a recognizable picture, like a corporate logo, without telling students what will happen later. Then assign each student’s instructions to a randomly chosen classmate, and have the classmate pretend to be the robot, attempting to follow the instructions and draw the same logo. In this fun activity, students act as robots, physically following the written instructions created by their peers.

After a few minutes, introduce a specific student who can share their results with the class, then ask their partner to share the initial instructions. This method gives students a chance to communicate with each other (“That’s not what I meant!”) and laugh and bond, while learning an important lesson.

This exercise teaches computer science students the difficulty and importance of writing clear instructions. I have seen this exercise not only teach pairs of such students meaningful lessons but encourage friendships that extended beyond my classroom.

Get students participating with these 45 classroom activities

4. Pass the “mic”

Monika Semma: As an instructor, it’s amazing how much information you can gather from a student-centered review session. Specifically, if you leave the review in the hands of your students, you can get an easy and thorough assessment of what is being absorbed, and what is being left by the wayside. The more you encourage participation, the more you’ll see where your class is struggling and the more comfortable students will become with course material. Interactive activities encourage students to communicate and share their conclusions, leading to better retention of information. During these sessions, students share their knowledge and insights with the entire class, making the review more engaging and collaborative. Here’s how to transform a standard review into one of your more popular classroom activities:

- A week before the review, ask students to email you two to five key terms or theories that they feel they need to brush up on. Take all that data and compress it until you have a solid working list of what students want to review most.

- In class, provide students with visual access to the list (I found writing all the terms on a chalkboard to be most effective). Instruct the class to have their notes out in front of them, with a pad of paper or blank Word document at their fingertips, and encourage them to take notes as the review is in progress.

- A trinket of sorts (I highly recommend a plush ball), used as a “microphone,” helps to give students equal opportunity to direct the review without putting individuals on the spot too aggressively. The rules are simple: she or he who holds the “mic” can pick one term from the list and using their notes, can offer up what they already know about the term or concept, what they are unsure of, or what they need more elaboration on.

- Actively listen to the speaker and give them some positive cues if they seem unsure; it’s okay to help them along the way, but important to step back and let this review remain student-centered. Once the speaker has said their piece, open the floor to the rest of the class for questions or additional comments. If you find that the discussion has taken a departure from the right direction, re-center the class and provide further elaboration if need be.

- Erase each term discussed from the list as you go, and have the speaker pass (or throw) on the “mic” to a fellow classmate, and keep tossing the ball around after each concept/term is discussed.

Students will have a tendency to pick the terms that they are most comfortable speaking about and those left consistently untouched will give you a clear assessment of the subjects in which your class is struggling, and where comprehension is lacking. Once your class has narrowed down the list to just a few terms, you can switch gears into a more classic review session. Bringing a bit of interaction and fun into a review can help loosen things up during exam time, when students and teachers alike are really starting to feel the pressure.

5. Use YouTube for classroom activities

Monika Semma: Do you remember the pure and utter joy you felt upon seeing your professor wheel in the giant VHS machine into class? Technology has certainly changed—but the awesome powers of visual media have not. Making your students smile can be a difficult task, but by channeling your inner Bill Nye the Science Guy you can make university learning fun again.

A large part of meaningful learning is finding interactive classroom activities that are relevant to daily life—and I can think of no technology more relevant to current students than YouTube.

A crafty YouTube search can yield a video relevant to almost anything in your curriculum and paired with an essay or academic journal, a slightly silly video can go a long way in helping your students contextualize what they are learning. For example, using videos featuring famous people can be a fun way to engage students and spark their interest in the lesson.

Even if your comedic attempts plunge into failure, at the very least, a short clip will get the class discussion ball rolling. Watch the video as a class and then break up into smaller groups to discuss it. Get your students thinking about how the clip they are shown pairs with the primary sources they’ve already read.

6. Close reading

Monika Semma: In the humanities, we all know the benefits of close reading activities—they get classroom discussion rolling and students engaging with the material and open up the floor for social and combination learners to shine. “Close reading” is a learning technique in which students are asked to conduct a detailed analysis or interpretation of a small piece of text. It is particularly effective in getting students to move away from the general and engage more with specific details or ideas. As part of close reading, you can have students identify and analyze a key vocabulary word from the text, encouraging them to focus on its meaning and usage within the written passage.

If you’re introducing new and complex material to your class, or if you feel as though your students are struggling with an equation, theory, or concept; giving them the opportunity to break it down into smaller and more concrete parts for further evaluation will help to enhance their understanding of the material as a whole.

And while this technique is often employed in the humanities, classroom activities like this can be easily transferred to any discipline. A physics student will benefit from having an opportunity to break down a complicated equation in the same way that a biology student can better understand a cell by looking at it through a microscope.In any case, evaluating what kinds of textbooks, lesson plans and pedagogy we are asking our students to connect with is always a good idea.

6 communication activities for college students

Brainwriting

Group size: 10 students (minimum)

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

This activity helps build rapport and respect in your classroom. After you tackle a complex lecture topic, give students time to individually reflect on their learnings. Have students write their responses to the guided prompts or open-ended questions before sharing them. Once students have gathered their thoughts, encourage them to share their views either through an online discussion thread or a conversation with peers during class time. Using exit tickets at the end of class helps teachers understand students’ learning and adjust plans accordingly.

Concept mapping

Group size: 10 students (minimum)

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

Collaborative concept mapping is the process of visually organizing concepts and ideas and understanding how they relate to each other. This exercise is a great way for students to look outside of their individual experiences and perspectives. Groups can use this tactic to review previous work or to help them map ideas for projects and assignments. You can also have students use concept mapping to organize key terms and concepts from a specific content area, reinforcing subject-specific vocabulary and understanding. For in-person classes, you can ask students to cover classroom walls with sticky notes and chart paper. For online classes, there are many online tools that make it simple to map out connections between ideas, like Google Docs or the digital whiteboard feature in Zoom.

Debate

Group size: Groups of 5–10 students

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

Propose a topic or issue to your class. Group students together (or in breakout rooms if you’re teaching remotely) according to the position they take on the specific issue. Ask the groups of students to come up with a few arguments or examples to support their position. Write each group’s statements on the virtual whiteboard and use these as a starting point for discussion. For the debate, have the students line up so each student can take turns presenting their arguments, ensuring everyone has an equal opportunity to participate. A natural next step is to debate the strengths and weaknesses of each argument, to help students improve their critical thinking and analysis skills.

Make learning active with these 45 interactive classroom activities

Compare and contrast

Group size: Groups of 5–10 students

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

Ask your students to focus on a specific chapter in your textbook. Then, place them in groups and ask them to make connections and identify differences between ideas that can be found in course readings and other articles and videos they may find. After the group discussions, have students share their findings with the rest of the group to encourage engagement and peer learning. This way, they can compare their ideas in small groups and learn from one another’s perspectives. In online real-time classes, instructors can use Zoom breakout rooms to put students in small groups.

Assess/diagnose/act

Group size: Groups of 5–10 students

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

This activity will improve students’ problem-solving skills and can help engage them in more dynamic discussions. Start by proposing a topic or controversial statement. Then follow these steps to get conversations going. In online classes, students can either raise their hands virtually or use an online discussion forum to engage with their peers.

- Assessment: What is the issue or problem at hand?

- Diagnosis: What is the root cause of this issue or problem?

- Action: How can we solve the issue?

Entry tickets

Entry tickets are a simple yet powerful way to engage students right from the beginning of class. To use entry tickets, teachers write a question or prompt related to the day’s lesson on the board as students enter the classroom. Each student writes their response on an index card, which serves as their “ticket” to participate in the lesson. This interactive learning strategy encourages students to start thinking critically about the material before the lesson even begins.

After collecting the entry tickets, teachers can invite students to share their answers with a partner, in small groups, or with the whole class. This sparks discussion, helps students connect prior knowledge to new concepts, and sets a collaborative tone for the rest of the lesson. Entry tickets can be used to review previous content, introduce new ideas, or quickly assess student understanding. By making entry tickets a regular part of your lesson plans, you create an interactive classroom environment where every student is engaged and ready to learn from the very start.

Improve interactive learning with a flipped classroom

The flipped classroom model transforms the traditional approach to teaching by having students learn foundational concepts at home and use class time for interactive activities. In this model, students watch videos, read articles, or review other materials before coming to class. Then, during class, teachers can focus on engaging students in hands-on projects, group discussions, and problem-solving exercises.

This approach allows students to learn at their own pace outside of class and come prepared to participate in more meaningful, interactive learning experiences. Teachers can organize students into small groups to discuss topics, work through challenging problems, or collaborate on projects. The flipped classroom encourages students to take an active role in their learning, promotes deeper thinking, and makes class time more engaging for everyone. By shifting the focus from passive listening to active participation, teachers can create a classroom environment where students are excited to learn and work together.

3 motivational activities for college students

Moral dilemmas

Group size: Groups of 3–7 students

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

Provide students with a moral or ethical dilemma, using a hypothetical situation or a real-world situation. Have students act out the moral dilemmas to explore different perspectives and deepen their understanding. Then ask them to explore potential solutions as a group. This activity encourages students to think outside the box to develop creative solutions to the problem. In online learning environments, students can use discussion threads or Zoom breakout rooms.

Conversation stations

Group size: Groups of 4–6 students

Course type: In-person

This activity exposes students’ ideas in a controlled way, prompting discussions that flow naturally. To start, share a list of discussion questions pertaining to a course reading, video or case study. Put students into groups and give them five-to-ten minutes to discuss, then have two students rotate to another group. The students who have just joined a group have an opportunity to share findings from their last discussion, before answering the second question with their new group. After another five-to-ten minutes, the students who haven’t rotated yet will join a new group, and the next student will participate in the ongoing discussion with their peers.

This or that

Group size: Groups of 5–10 students

Course type: Online (synchronous or asynchronous), in-person

This activity allows students to see where their peers stand on a variety of different topics and issues. Instructors should distribute a list of provocative statements before class, allowing students to read ahead. Then, they can ask students to indicate whether they agree, disagree or are neutral on the topic in advance, using an online discussion thread or Google Doc. In this activity, students choose their stance on each topic, which encourages active participation and ownership of their opinions. In class, use another discussion thread or live chat to have students of differing opinions share their views. After a few minutes, encourage one or two members in each group to defend their position amongst a new group of students. Ask students to repeat this process for several rounds to help familiarize themselves with a variety of standpoints.

Project-based learning

Project-based learning is a dynamic approach that puts students at the center of the learning process. In this model, students work in groups to tackle real-world projects that require them to research, problem-solve, and create something meaningful. Teachers design projects that align with learning objectives, allowing students to explore topics in depth and apply what they’ve learned in practical ways.

Throughout the project, students are engaged in interactive learning as they collaborate, share ideas, and think critically about the subject matter. Teachers act as facilitators, guiding students and providing support as needed. By the end of the project, students present their findings or products, demonstrating their understanding and creativity. Project-based learning not only helps students develop important skills like teamwork and communication, but also makes the learning process more engaging and relevant. When students are actively involved in creating and presenting their work, they become more invested in their own learning journey.

6 team-building classroom activities for college students

Snowball discussions

Group size: 2–4 students per group

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

Assign students a case study or worksheet to discuss with a partner, then have them share their thoughts with the larger group. Use breakout rooms in Zoom and randomly assign students in pairs with a discussion question. After a few minutes, combine rooms to form groups of four. After another five minutes, combine groups of four to become a larger group of eight—and so on until the whole class is back together again. This process ensures that the activity eventually involves the entire class, promoting participation and collaboration among all students.

Make it personal

Group size: Groups of 2–8 students

Course type: Online (synchronous), in-person

Provide students with a moral or ethical dilemma, using a hypothetical situation or a real-world situation. Then ask them to explore potential solutions as a group. This activity encourages students to think outside the box to develop creative solutions to the problem. In online learning environments, students can use discussion threads or Zoom breakout rooms. Mystery Box encourages students to guess contents based on tactile clues, fostering critical thinking and observation skills, which can be a fun and engaging addition to such activities.

After you’ve covered a topic or concept in your lecture, divide students into small discussion groups (or breakout rooms online). Using a fun way, such as having students share stories or create visual scenes, can encourage them to reflect on their personal connections to the material. Ask the groups questions like “How did this impact your prior knowledge of the topic?” or “What was your initial reaction to this source/article/fact?” to encourage students to reflect on their personal connections to the course concepts they are learning.

Philosophical chairs

Group size: 20–25 students (maximum)

Course type: In-person

A statement that has two possible responses—agree or disagree—is read out loud. Depending on whether they agree or disagree with this statement, students move to one side of the room or the other. This activity is similar to the Four Corners activity, where students move to different corners of the room based on their opinions, encouraging movement and discussion. After everyone has chosen a side, ask one or two students on each side to take turns defending their positions. This allows students to visualize where their peers’ opinions come from, relative to their own.

Get more interactive classroom activities here

Affinity mapping

Group size: Groups of 3–8 students

Course type: Online (synchronous)

Place students in small groups (or virtual breakout rooms) and pose a broad question or problem to them that is likely to result in lots of different ideas, such as “What was the greatest innovation of the 21st century?” or “How would society be different if _*__* never occurred?” Ask students to generate responses by writing ideas on pieces of paper (one idea per page), on index cards for easy sorting and organization, or in a discussion thread (if you’re teaching online). Once lots of ideas have been generated, have students begin grouping their ideas into similar categories, then label the categories and discuss why the ideas fit within them, how the categories relate to one another and so on. Jigsaw problem solving activities allow students to work in groups to solve complex problems collaboratively. This allows students to engage in higher-level thinking by analyzing ideas and organizing them in relation to one another.

Socratic seminar

Group size: 20 students (minimum)

Course type: In-person

Ask students to prepare for a discussion by reviewing a course reading or group of texts and coming up with a few higher-order discussion questions about the text. As part of their preparation, have students create written questions to bring to the seminar. In class, pose an introductory, open-ended question. From there, students continue the conversation, prompting one another to support their claims with evidence from previous course concepts or texts. There doesn’t need to be a particular order to how students speak, but they are encouraged to respectfully share the floor with their peers.

Concentric circles

Group size: 20 students (maximum)

Course type: In-person

Students sit in two circles: an inner circle and an outer circle. Each student on the inside is paired with a student on the outside; they sit facing each other. Pose a question to the whole group and have pairs discuss their responses with each other. After three-to-five minutes, have students on the outside circle move one space to the right so they are standing in front of a new person. Pose a new question, and the process is repeated, exposing students to the different perspectives of their peers.

Interactive learning tools

Interactive learning tools are a game-changer for both teachers and students, making lessons more engaging and accessible. These tools include educational software, apps, games, and online resources that support interactive learning in the classroom. Teachers can use these tools to create fun and interactive lessons, quizzes, and activities that cater to different learning styles and abilities.

For example, teachers might use online platforms to set up interactive whiteboards, host virtual labs, or facilitate discussion forums where students can share ideas and ask questions. Students can also use interactive tools to create their own content, such as videos, podcasts, or digital presentations, to show what they’ve learned. Incorporating interactive learning tools into your lesson plans not only makes learning more fun, but also encourages students to take an active role in their education. By embracing these tools, teachers can create a classroom environment where every student is engaged, motivated, and excited to learn.

Interactive classroom activities, in short

Final thoughts

Making your classes more interactive should help your students want to come to class and take part in it. Giving them a more active role will give them a sense of ownership, and this can lead to students taking more pride in their work and responsibility for their grades. Project-based learning, where students work on a project over an extended period, can cultivate critical thinking and collaboration, further enhancing their engagement.

Use these 45 classroom activities in your course to keep students engaged

The flipped classroom model, where students watch lectures or read content at home, can also free up class time for interactive activities, making learning more engaging and participatory.

A more interactive class can also make things easier for you—the more work students do in class, the less you have to do. Even two minutes of not talking can re-energize you for the rest of the class. Live polls and quizzes can also be used for instant feedback to keep students engaged during lessons. Additionally, interactive assessments, such as Top Hat’s interactive polls and quizzes, make learning fun and competitive, further enhancing student engagement.

Plus, these six methods outlined above don’t require any large-scale changes to your class prep. Set up a couple of activities in advance here and there, to support what you’ve been doing, and plan which portion of your class will feature them.

The reality remains that sometimes, students do have to be taught subject matter that is anything but exciting. That doesn’t mean that we can’t make it more enjoyable to teach or learn. Experiments and simulations, for example, provide hands-on activities that create immersive learning experiences and develop higher-order thinking skills. Hands-on projects can include activities like building models, conducting experiments, or creating art that illustrate key concepts. Improv activities help students engage in the learning process by encouraging thinking on their feet and collaboration. It may not be possible to incorporate classroom activities into every lecture, but finding some room for these approaches can go a long way in facilitating a positive learning environment.

And let’s not forget, sometimes even an educator needs a brief departure from the everyday-ordinary-sit-and-listen-to-me-lecture regimen.

Energize your college classroom and get discussions flowing. Download The Best Classroom Activities for College Courses to engage and motivate students.

Frequently asked questions

1. What are some effective interactive classroom activities for college students?

Interactive classroom activities such as think-pair-share, live polling, and group problem-solving encourage students to engage deeply with course material. These activities also promote class discussion and help instructors pose meaningful class discussion questions to spark critical thinking.

2. How do interactive classroom activities improve class discussion?

Interactive classroom activities create opportunities for students to share diverse perspectives and collaborate on ideas. When students participate actively, class discussion becomes more dynamic, and instructors can build on these moments with targeted class discussion questions to deepen understanding.

3. How can instructors use class discussion questions in interactive classroom activities?

Instructors can integrate class discussion questions into interactive classroom activities like debates, case studies, and peer reviews. This approach encourages participation, strengthens communication skills, and ensures every student contributes meaningfully to the class discussion.