Back in April 2020, with all the lovely weather we’d been having, I was yearning for a holiday.

But I wasn’t sure the offer I was reading from a tour operator really stacked up.

“Because of Covid-19”, said the brochure, “by the time your holiday due date arrives we might not be able to get you there and even if you get there yourself, we might not have any of the facilities open. If that’s the case and you book anyway, please note you’ll neither be entitled to a refund nor a discount, but you will get to watch some people swimming in a pool on YouTube. You’ll also be able to join in with our holiday chat on Zoom. And you jolly well better risk booking it – because holidays will be much harder to come by next year!”

It sounded pretty unreasonable to me. And probably unlawful. But someone somewhere in central government appeared to disagree.

In the impact assessment that accompanied the emergency Coronavirus Bill a month previously, officials had explained the implications of the power to close campuses – and as well as discussion on how compensation for universities might work, the section contained this ominous line on students:

Where there are concerns to protect HEPs from being sued for reneging on their consumer protection (and/or contractual) obligations in the event of course closure we believe force majeure would be relevant.

For me, it was that that set the tone for the entire way in which the pandemic was handled when it came to students and universities. The understanding was that students would pay. And they very much did – in more ways than one.

As such, ever since March 2020, I’ve been imagining the moment when a minister or senior civil servant might be called by an inquiry to account for the catalogue of catastrophes that were the handling of higher education during Covid.

I wanted to know if then-universities minister Michelle Donelan really believed that students would succeed if they did as she suggested and made a complaint about quality. I was keen to understand why campuses were being told to operate at 30 per cent capacity while the halls on their edges operated at 100 per cent.

I wanted to know whether DfE’s plan in the run into September really was to get everyone to turn up, stick it out for a few weeks so that the fee liability kicks in, and then blame external factors when the sector inevitably had to shut campuses back down.

I wanted to know why students were consistently left out of financial compensation measures, ignored in guidance and policies, told to pay the rent on properties they were told not to occupy, gaslit over quality and “the student experience”, and repeatedly blamed for transmitting the virus when they’d been threatened with losing their place if they deferred.

Above all, I wanted to know why anyone, at any point, really thought that they should be paying full fees for the isolating omnishambles that they eventually experienced.

I had reason to be optimistic. The UK COVID-19 Inquiry was set up as an independent public inquiry examining the UK’s preparedness and response to the pandemic through multiple modules.

Module 8, which opened in May 2024, was to focus specifically on the impact of the pandemic on children and young people across all four UK nations. Universities and students were included in Module 8 because the inquiry defines “young people” to include those aged 18-25 who attended higher education or training during the pandemic.

It was supposed to examine the full spectrum of educational disruption from early years through to universities, investigating decisions about closures, reopenings, exam cancellations, online learning adaptations, and issues like student isolation in halls of residence, as well as the broader impact on mental health, wellbeing, and long-term consequences for this generation.

Well guess what. Yesterday was the final day of three weeks of testimony from ministers, civil servants, regulators, charities and other experts. And the total number of times that university students have been mentioned? Zero.

Hope springs eternal

If I think back to that March 2020 impact assessment, the logic appeared straightforward – with DfE struggling to extract funding from the Treasury for education, let alone for universities or students, the simplest solution to an assumption that Covid would bankrupt the sector was to ensure fee income continued flowing.

Universities wouldn’t go bust as long as students could be persuaded not to defer en masse, which would have created a difficult demand spike the following year.

The problem was how that was done. By the end of March, all sorts of people were calling for a Big Freeze – a pause to September enrolment. The case was straightfoward – universities couldn’t deliver what they were promising, students couldn’t make informed decisions, and the public health risks were unknown.

But the government’s response was Education Secretary Gavin Williamson announcing in June that there was “absolutely no need for students to defer”, while universities Minister Michelle Donelan told students not to defer because “the labour market will be precarious” and that universities had “perfected their online offer” – despite having only weeks to prepare.

Donelan repeatedly pushed a “business as usual” message, telling prospective students that September would go ahead with perhaps some online teaching but no real disruption worth worrying about. The Department for Education (DfE) published generic FAQs and social media messages encouraging students to enrol as normal, despite universities having no idea what they could actually deliver. Later in the year, Universities UK joined in with a social media campaign that told students going to university that September would show “strength” and that they “refuse to be beaten”.

Meanwhile the Office for Students (OfS) imposed and then repeatedly extended a moratorium on unconditional offers – ostensibly to protect students from being rushed into decisions – but without addressing the fundamental problem that universities couldn’t provide the “material information” required by consumer law about what students would actually receive for their money.

The regulatory system proved entirely inadequate for the crisis. Student Protection Plans, which were supposed to set out risks to continuation of study and mitigation measures, had never been properly enforced and became instantly obsolete. When COVID hit, the regulator made no move to require universities to update their risk assessments, even as financial viability, course delivery, access to facilities and support for disabled students all became dramatically more precarious.

The Competition and Markets Authority’s consumer protection requirements – which clearly stated students must receive what they expected – were essentially ignored, with DfE telling students that as long as “reasonable efforts” and “adequate” alternatives were provided, they shouldn’t expect refunds. Nobody defined what “reasonable” or “adequate” meant in a pandemic, leaving students with no meaningful protections despite paying £9,250 in fees.

The absence of any coordinated national approach left universities making contradictory announcements and students facing impossible choices. Cambridge declared all lectures would be online until summer 2021, while Bolton promised a fully “COVID-secure” campus with temperature scanners and face masks. Both still expected students to move house and live in halls of residence, with no clear government guidance on whether mass student migration was safe or legal under social distancing rules.

There was no extension of maintenance loans despite part-time work vanishing, no student furlough scheme to allow pausing or extending studies, no support for those whose courses couldn’t meaningfully continue, and no plan for accommodation contracts due to start on 1 July.

Students faced being charged full fees for a drastically reduced experience, with no agency over whether to accept major changes to their courses, no compensation mechanisms, and no honest assessment from universities about what would actually be available – all while being told they should “take time to consider their options” and make “well-informed choices” without any reliable information to base those choices on.

Summertime scramble

By June, the absence of any meaningful government planning or support became intolerable. The Office for Students told a student conference that provision needed to be “different but good – not different but bad” but when pressed on what “good” meant, admitted it was a “very good question” and had no answer.

Its baseline standards were expressed only as outcomes-based metrics that would take 18 months to show up in surveys, leaving universities and students with no clarity about minimum acceptable standards for the pandemic era. Its position appeared to be that it would only intervene if there was a major risk to provider finances, not student welfare – representing “provider interest” rather than “student interest”.

The government’s approach to student hardship was even worse. After Chancellor Rishi Sunak repeatedly claimed the government was doing “whatever it takes” for people affected by COVID-19, the Department for Education announced on 4 May a £46 million “support package” for students in financial difficulty.

But this wasn’t new money at all – it was just two months’ worth of existing “student premium” funding that universities were being told they could “repurpose” for hardship funds. The actual sum available was far smaller once you accounted for the fact that much of this funding was already committed or spent on staff costs for widening participation work that hadn’t stopped. In Canada, by contrast, the government announced the equivalent of £736 per month per student until the end of the summer.

As August arrived with weeks to go before term started, the sector lurched towards chaos. Despite OfS CEO Nicola Dandridge demanding in May that students receive “absolute clarity” about what was on offer before confirmation and clearing, and OfS Chair Michael Barber saying on results day that “universities should set out as clearly as possible what prospective students can expect”, the reality was almost total opacity. Most universities were still offering vague “blended” mood music rather than specifics, with course pages unchanged from before the pandemic.

On August 30th, the University and College Union called on universities to “scrap plans” to reopen campuses, warning they could become “the care homes of a second wave”. Independent SAGE had published detailed recommendations on 21 August including mandatory testing, online-only teaching except for essential practical work, and COVID-safe workplace charters – but with students already arriving to quarantine, any changes were impossibly late.

Fresh guidance

Scotland’s guidance emerged on 1 September, but contained no provision for mandatory testing despite weeks of signals that it would be required, and placed responsibility for enforcement of quarantine and disciplinary measures firmly on universities without clarity on their jurisdiction over private accommodation.

Then at precisely 1.18am on Thursday 10 September, the Department for Education published guidance for higher education on reopening buildings and campuses in England – and in many ways, it symbolised handling throughout. It insisted on “provider autonomy” and made clear that “it is for an HE provider, as an autonomous institution” to manage risks, while simultaneously dictating detailed operational requirements.

The responsibility allocation framework seemed systematically designed to deflect blame from government onto universities and students. Despite acknowledging that “mass movement” of students created risk and that Public Health England and local authorities logically should lead outbreak response, the guidance repeatedly assigned universities responsibility for “ensuring students are safe and well looked after” – an impossible mandate for commuter students and adults in private accommodation.

The testing infrastructure was inadequate and contradictory – walk-through test sites weren’t going to be ready until late October, asymptomatic testing was restricted due to “national strain on testing capacity,” all while universities were warned against running their own testing programs due to complex legal obligations. Contact tracing guidance had obvious holes, particularly compared to Scottish requirements, and did nothing to address the myriad disincentives students faced in getting tested or self-isolating.

The most damning part was arguably the government’s fatalistic acceptance that outbreaks would occur while simultaneously allowing the “mass migration” to proceed. Both SAGE analysis and the guidance itself acknowledged that increased infections and outbreaks were “highly likely,” yet the entire year could have been “default online.” The government was “doing all it can” while creating the very conditions guaranteed to spread the virus, then pre-allocating blame to students and universities.

Mental health support amounted to telling autonomous institutions they were “best placed” to handle it themselves, backed by that £256 million that was actually a cut from the previous year’s £277 million – only accessible by making swingeing cuts elsewhere. The guidance exempted halls of residence from gathering limits without explaining why publicly, mentioned nothing about the 200,000 students in private halls, and dumped international student hardship onto universities despite “no recourse to public funds” rules.

Overall, the government’s handling of the student return to campus in September 2020 was marked by confusion, contradictions and last-minute changes that left universities and students scrambling. Key regulations like the “rule of six” were published at 23:44 on 13 September – just 16 minutes before they came into force – giving institutions no time to communicate changes to students despite DfE saying providers were “responsible” for ensuring awareness.

The lack of clarity extended to fundamental questions like what constituted a “household” in student accommodation – with profound implications for who could socialise with whom, who had to self-isolate and whether students could return home at weekends – yet no clear legal definition was provided despite fines of up to £10,000 being threatened.

Different ministers gave contradictory guidance on who was responsible for refunds and financial support – with Nicola Dandridge saying it was a matter for government, Number 10 saying it was a matter for universities and Gavin Williamson suggesting students could complain through the Office for Students.

By now, the Secretary of State was repeatedly claiming that £256 million was available for hardship funding when this was actually existing student premium funding that had been cut in May, and trumpeted £100 million for digital access that turned out to be a schools fund covering perhaps 650 care leavers worth around £195,000 in total.

SAGE advice to government warned that a national coordinated outbreak response strategy was urgently needed, that universities should provide dedicated accommodation for isolation and that enhanced testing would be required for clusters. None of this made it into DfE guidance. Instead public health teams were left to improvise, leading to entire buildings of 500 students being locked down when the “household” concept collapsed, while students who actually had Covid were legally allowed to travel home to self-isolate there.

The quality of data and assumptions going into SAGE about student behaviour was poor – minutes from September meetings showed “low confidence and poor evidence base” yet still concluded students posed risks of transmission, particularly at Christmas when they would “return home” – a framing that completely ignored commuter students and those who travelled home every weekend.

And we’re off

As term began, research from Canada and the US suggested reopening campuses substantially increased community infections, yet the government pushed ahead without adequate testing infrastructure in place – with even Dido Harding admitting to Parliament that Test and Trace had failed to predict demand from students despite the obvious likelihood of “Freshers’ Flu” generating testing requests.

Students were singled out for treatment that was stricter than other citizens yet without equivalent support – expected to self-isolate without access to the financial cushions available to others, unable to claim Universal Credit, threatened with £10,000 fines and faced with university disciplinary action including expulsion.

Universities Scotland announced students must avoid all socialising outside their households and not go to bars or hospitality venues – a “voluntary lockdown” that was later rowed back as merely a “request” after it caused uproar. Meanwhile Exeter implemented a “soft lockdown” asking only students not to meet indoors with other households, and Scotland threatened to prevent students returning home at weekends – measures that had never appeared in any government guidance or playbook yet were being invented on the fly by local officials.

The sector was essentially told to operate minimum security prisons while still charging full fees for an experience that bore no resemblance to what had been promised, with no clarity on legal rights to refunds despite the Competition and Markets Authority having provided detailed guidance on partial refunds for other sectors like weddings and nurseries. The fundamental question of what students were supposed to do all week beyond online lectures was never answered – and the predictable result was isolation, mental health crises and outbreaks that vindicated warnings the sector had been making since summer.

By October, a cascade of evidence had emerged showing fundamental government failures in managing the return of students to universities. The central mistake was allowing student accommodation to operate at 100 per cent capacity whilst carefully reducing every other setting to around 30 per cent, including lecture theatres, libraries, corridors, catering outlets, shops, bars, public transport and social spaces. SAGE had warned as early as September that housing posed major transmission risks due to large household sizes, high density occupancy, poor quality housing and poor ventilation.

Despite commissioning advice from SAGE on the role of housing in transmission, neither the Department for Education nor the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government acted on recommendations to reduce occupied density. DfE had asked for specific guidance on student accommodation as early as 8 July, yet the resulting advice failed to implement SAGE’s core recommendation that “we really ought to have been reducing occupied density”.

Ministers instead expected students to spend carefully distanced time on campus for three or four hours weekly, but for the rest of the week to remain in spaces “never designed to be used this intensively, with inevitable results”.

The government rejected crucial scientific advice at multiple points. On 21 September, SAGE recommended that “all university and college teaching to be online unless face-to-face teaching is absolutely essential” as part of a package to reverse exponential rises in cases, estimating this would reduce the R number by 0.3. Ministers explicitly rejected this recommendation, with universities minister Michelle Donelan maintaining the line that “we decided to prioritise education”, despite students being confined to online learning in tiny rooms anyway.

The government also failed to implement mass testing strategies recommended by both SAGE and the CDC, despite promising repeatedly to deliver testing capacity. Students requiring self-isolation received no financial support, being excluded from the £500 Test and Trace Support Payment available to other citizens on low incomes, with most local authorities refusing to include students in discretionary schemes.

SAGE had explicitly warned that “students in quarantine require substantial support from their institution during the period” and that “failing to provide support will lead to distress, poor adherence and loss of trust”, yet the government provided no funding beyond expecting universities to redirect existing hardship funds.

Jingle bells

As the country looked to Christmas, no UK-wide coordination existed for managing student migration, with four-nations discussions chaired by Michael Gove only beginning in late October. Guidance on safely managing returns remained unpublished throughout October despite ministers knowing since March that student migration posed transmission risks.

Students fell through gaps between departments, with DfE, MHCLG and DWP unable to agree responsibility for financial support, testing strategies or housing standards. Working students in hospitality and retail lost employment income but found themselves excluded from benefits, discretionary payments and adequate hardship fund support, with some resorting to commercial credit to pay rent arrears.

As Christmas got closer, the government’s handling of higher education descended into a familiar pattern of late guidance, ignored scientific advice and policy decisions designed to avoid financial liability. DfE repeatedly issued vague guidance that left universities to make difficult decisions about face-to-face teaching – explicitly to avoid being drawn into fee refund claims – while ministers like Michelle Donelan insisted that “blended learning” must continue despite SAGE’s repeated recommendations to move teaching online.

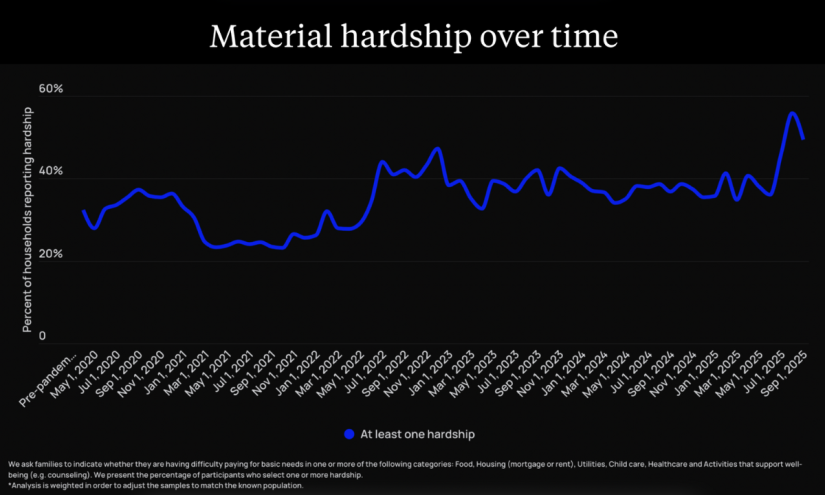

When guidance on Christmas travel and January’s return finally emerged, it came so late that universities couldn’t meaningfully prepare, and students faced impossible choices between physical and mental health. Office for National Statistics data revealed that 65 per cent of students in mid-November were receiving zero hours of face-to-face teaching – despite government rhetoric about prioritising in-person education – while student anxiety levels (6.5 out of 10) dramatically exceeded the general population (4.3 out of 10).

The government’s failure to address accommodation density became undeniable when Public Health Scotland published evidence that traditional halls of residence with “households” of up to 30 people had fuelled transmission, with almost 3,000 cases associated with student accommodation and the majority occurring in a three-week period in September-October.

Students described having to remain in small rooms without access to food, fresh air or exercise during self-isolation, with some international students arriving to empty buildings with no support, no SIM card to order food and no meaningful mental health provision despite contractual promises.

The government’s solution for Christmas was to create complex household bubble rules that meant some families with multiple students away from home couldn’t all gather together, while hundreds of international students and care leavers faced spending the entire break isolated in university towns with no meaningful support beyond opened canteens where they still couldn’t mix with others.

Auld lang syne

As the new year approached, the government announced a “staggered return” that would see some students barred from returning to paid-for accommodation for up to nine weeks, with no rent rebates offered – and Minister Donelan explicitly telling universities that “any issue about accommodation is for the universities to address with students”. The mass testing programme was revealed to have serious efficacy problems – with one study suggesting the lateral flow tests detected just over 3 per cent of cases – and participation rates of around 7 per cent in Scotland.

Despite mounting evidence about the failure to deliver “blended learning”, worsening mental health and the concentration of infection in accommodation rather than teaching spaces, ministers continued to frame policy around getting students “back to campus” while simultaneously telling them to stay away, creating a chaotic situation where students couldn’t plan, universities couldn’t prepare and the January term faced collapse before it began.

By January 2021, the government had announced that some students could return to campus, but the policy was riddled with problems from the start. Michelle Donelan’s attempt to specify eligible subjects using HeCOS vocabulary was marred by missing code numbers and duplications, and ignored both professional bodies’ actual requirements and basic public health principles. The Department for Education essentially determined which campuses would see large student numbers purely by virtue of subject mix – meaning some universities like King’s College London expected over 6,500 students while others like LSE had virtually none.

Worse still, the policy showed no consideration of local Covid case rates, with the data showing numerous providers expecting large numbers of “tranche one” students in areas with high infection prevalence. No professional body was actually insisting students be on campus during a “terrifying third phase of a pandemic” – yet the government was.

The legal restrictions that came into force on 5th January created even more chaos. Nothing in the regulations actually changed specifically for higher education, yet guidance from DfE contradicted existing legal exemptions – for example, insisting that campus catering had to be takeaway only when the law explicitly allowed “cafes or canteens at a higher education provider” to open.

The movement rules allowed students studying away from home to move back to their student housing before 8th February, yet DfE guidance urged them to stay away – creating a situation where students were being told they couldn’t use properties they were legally entitled to occupy and were being forced to pay rent on.

Meanwhile, emerging research painted a terrifying picture that government policy largely ignored. Cambridge’s genomics work suggested little transmission between students and the wider community in their specific context, but a separate study of 30 universities found that 17 campus outbreaks translated directly into peaks of infection in their home counties within two weeks.

The government’s lateral flow testing programme was riddled with problems. Data from Scotland’s pre-Christmas exercise showed that 28.5 per cent of positive lateral flow tests were false positives when PCR-confirmed – yet the government then removed the requirement for PCR confirmation in England in February, potentially causing thousands to self-isolate unnecessarily while eliminating the data needed to assess test accuracy.

Research showed the type of test mattered enormously and that high participation rates were key to any testing programme’s success, yet participation in university testing remained abysmal – in one week in February just 100,000 tests were conducted across English higher education, suggesting only around 2.5 per cent of students were being tested despite government insistence on twice-weekly screening. The cost per positive result in community testing was around £20,000 when prevalence was low, and the government appeared to have learned nothing from the pre-Christmas pilot about why students weren’t engaging.

On accommodation, ministers merely “urged” landlords to offer rent rebates while keeping students away from campuses, refusing to underwrite rebates or mandate them. And the government’s handling of vaccination access created additional problems – students studying away from home could only access vaccines where their GP was registered, but the NHS insisted students could only be registered with one GP at a time. It meant that students isolating at home due to health conditions were offered vaccines at their university address hundreds of miles away, creating impossible choices.

Summertime sadness

As the term continued, universities minister Michelle Donelan repeatedly told parliament that the Office for Students was “actively monitoring” the quality of provision and that students dissatisfied with teaching could complain to the OIA for potential refunds. But OfS confirmed it wasn’t monitoring quality in any meaningful sense – it had merely made some calls to universities in tier 3 areas – and the OIA re-clarified that it couldn’t adjudicate on academic quality matters. The disconnect between ministerial assurances and regulatory reality left students without the redress mechanisms they had been promised.

Similarly, the government’s approach to student return dates proved chaotic – initially planning for staggered returns from mid-February, then pushing back to March 8th for only “practical” courses, then suggesting a review “by the end of Easter holidays” for everyone else. By May, the government confirmed remaining students could return from Step 3 on May 17th – by which point teaching had largely finished for most.

The maintenance loan system created further problems – initially, officials planned to reassess loans downward for students no longer in their term-time accommodation, despite many still paying rent. Only after intervention was this policy reversed, with “overpayments” instead added to loan balances. Meanwhile, students on courses requiring practical work faced significant challenges – many would be “unable to complete” without access to facilities yet received no extensions to maintenance support or additional hardship funding.

The graduate employment situation was similarly neglected, with unemployment among recent graduates rising to 18 per cent for both graduates and non-graduates, reaching 33.7 per cent for young Black graduates. The government’s response was merely to create a six-step collection of weblinks hosted on the OfS website rather than meaningful job guarantee schemes or funded postgraduate study.

A failure to learn

There are so many other aspects I haven’t covered here, and so many more issues I’d have loved to see ministers account for. The international student experience deserves its own inquiry – from those trapped abroad unable to access online teaching due to time zones and VPNs, to those who arrived to empty campuses having paid flights and deposits they couldn’t recover.

The impact on disabled students who lost access to essential support services. The postgraduate researchers who saw years of lab work destroyed or delayed. The creative arts students paying full fees for courses they literally couldn’t do from their bedrooms. The teaching quality collapse that was dismissed as “blended learning”. The mental health crisis that was met with a cut to support funding dressed up as additional help. The list is almost endless.

But even if all these issues had been put to ministers at the inquiry, even if we’d heard testimony about employment, housing, transport, testing, health, isolation support, and student finances, we’d likely have faced the same problem we always do with students and higher education. Just as we see outside of pandemics, other government departments simply don’t think about students.

They’re not on the radar at the Treasury, at MHCLG, at DWP, at DHSC. Students fall through the gaps between departmental responsibilities, and the Department for Education – already stretched covering schools, further education, and early years – doesn’t have the influence, the power, or the capacity to force the student interest to be considered in decisions made elsewhere.

When Test and Trace payments were designed, nobody thought about students. When furlough was created, nobody thought about students. When housing regulations were written, nobody thought about students. And DfE either didn’t notice – or couldn’t do anything about it.

The problem is that if the decisions aren’t examined, the lessons won’t be learned. And there are crucial lessons that go far beyond the specifics of this pandemic.

The first is about responsibility and coordination. Throughout the entire saga, nobody seemed to be in charge. Was it DfE setting the policy? Was it universities exercising their autonomy? Was it local public health teams managing outbreaks? Was it MHCLG regulating housing? The answer appeared to be all of them and none of them, with each able to blame the others when things went wrong.

The tension between treating universities as autonomous institutions who should be “free” to make decisions, and then dictating detailed operational requirements while disclaiming responsibility for the outcomes, was never resolved. The sector demanded provider autonomy and then was sore when society blamed providers when they made autonomous decisions that some didn’t like.

Second, there’s the fundamental question of whether universities are part of the education system or something else entirely. They were conspicuously left out of education prioritisation decisions, treated neither as essential education that should continue (like schools) nor as adults who could make their own choices (like the general population).

Instead they occupied a weird middle ground where they were expected to operate like big schools – following government guidance, prioritising in-person education, being “responsible” for students – but with none of the government support or coordination that schools received. Students were simultaneously infantilised (being told they couldn’t be trusted to socialise responsibly) and abandoned (being told they were autonomous adults who should sort out their own problems).

Third, the pattern of guidance arriving impossibly late – or not at all – for me was a systematic failure to (scenario) plan. Regulations published 16 minutes before coming into force. Christmas travel guidance arriving when students had already booked transport. January return policies announced in December. Testing strategies finalised after students arrived. It wasn’t just poor planning – it was policy-making that appeared designed to avoid being pinned down, to maintain government flexibility at the expense of everyone else’s ability to prepare. And crucially, it was lateness that consistently disadvantaged students while protecting government and institutions from liability.

Fourth, the entire approach suggested to me an implicit hierarchy where protecting university finances trumped protecting students. That impact assessment in March 2020 said the quiet part out loud – force majeure would be relevant because universities had to be protected from being sued for breaking their consumer obligations.

Everything else flowed from that – encouraging enrolment even when delivery was uncertain, maintaining full fees regardless of quality, shifting hardship costs onto universities through repurposed funding, avoiding clear guidance that might create refund obligations, and telling students to complain to regulators who couldn’t actually help them. The system was designed to keep money flowing, not to deliver value or protect students.

And fifth, regulatory failure was baked in from the start. In England, the Office for Students proved entirely unfit for purpose in a crisis – unable to define quality standards, unwilling to intervene on student welfare, focused on provider finances rather than student interests, and apparently content to let ministers mislead Parliament about the protections it was providing. The gap between what ministers promised (monitoring, complaints routes, refunds) and what regulators could actually deliver left students without redress at the precise moment they needed it most.

None of these lessons are being learned because none of these decisions are being examined. And perhaps that absence reflects something deeper. Everyone involved – universities, the Office for Students, the Department for Education, ministers – were invested in suggesting that what was planned would work, was working, and did work. Partly that was about reputation. Partly it was about liability. Partly it was about avoiding the cost of refunds.

But the effect was the same – it prevented and continues to prevent any honest reckoning about what didn’t work, who was failed, who was damaged, and who was let down. That, on Radio 4’s More or Less a few weeks ago, I couldn’t answer the question how much learning had been lost, or what the impacts were on students, should be a source of deep national shame.

Admitting the scale of the failure would’ve meant admitting the scale of what was owed. But instead we got a collective fiction that “blended learning” was comparable to what students had signed up for, that online education from bedroom prisons was a reasonable substitute for the university experience, that students complaining about quality were just being difficult. The investment in that fiction has been so total that even now, when the statutory inquiry is supposed to be learning lessons, it can’t examine what actually happened – because the evidence on impacts is so thin.

Again and again

It’s worth saying that everyone almost certainly did their best in impossible circumstances. From university staff pivoting to online teaching overnight, to SU officers running Zoom pub quizzes to combat isolation, to professional services teams working around the clock to support students in crisis – there were countless unsung heroes who made it all a little less miserable. Nobody wanted this. Nobody planned for it. Everyone was doing what they could with the resources and guidance available. And that deserves recognition.

But the truth is that once students are paying individually for higher education – once it became a consumer market with £9,250 fees and interest-bearing loans and the language of student choice and value for money – doing your best isn’t enough. If you can’t deliver what was promised, “we tried our best” doesn’t cut it when someone is personally £50,000 in debt for the privilege.

The hyper-marketisation of higher education came with consumer protections and Competition and Markets Authority guidelines and material information requirements precisely because students weren’t just participating in education anymore – they were purchasing it. Neither the sector nor the government can have it both ways. You can’t charge consumer prices and then claim education is special and different when it comes to consumer rights.

You can make a reasonable case in other policy areas about whether central government or local authorities or devolved administrations or individual departments should be in charge of this budget or that decision. There are legitimate debates about the boundaries of autonomy and accountability, about who’s best placed to make decisions about housing or testing or public health interventions.

But what I can’t get over – and what I don’t think we should let anyone forget – is the assumption that was there from the very beginning, baked into that March 2020 impact assessment and every decision that followed – that students would pay for pretty much everything that was done to them, and everything that wasn’t done for them.

They’d pay full fees for reduced teaching. They’d pay rent on accommodation they were told not to use. They’d pay for support services that were closed. They’d pay for facilities they couldn’t access. They’d pay for an experience that bore no resemblance to what they’d signed up for. They’d pay for the privilege of being locked in their rooms, blamed for spreading a virus, threatened with fines and expulsion, excluded from the financial support available to everyone else, and told to be grateful that university was happening at all.

And pay they did. While being gaslit about quality, lied to about protections, and blamed for their own misery.

As Kate Ansty of the Child Poverty Action Group said in her oral evidence, to protect inside a pandemic, we must protect outside a pandemic. And as Sir John Cole said in his oral evidence, young people have played their part – society owes them a debt. Not the other way around.

If another pandemic happens, or another national emergency that affects higher education, I fear that exactly the same mistakes will be made. We still won’t know who’s in charge. Government will still treat universities as simultaneously autonomous and controlled. It will still issue guidance too late for anyone to use it. It will still prioritise institutional finances over student welfare. It will still leave students excluded from support available to everyone else. We’ll still have regulators who can’t regulate.

And students will still be blamed for the consequences of decisions made for them, about them, and without them.