Nora Mitchell is a rising 2L at Drexel University and a FIRE Summer Intern.

On July 7, Barnard College settled a lawsuit from students who claimed the institution had failed to address student accounts of anti-Semitism on campus. In the settlement, Barnard agreed to establish a Title VI Coordinator position, sever communication with the student group Columbia University Apartheid Divest, and prohibit the use of face masks during campus protests — a move that is becoming increasingly popular across college campuses.

Mask bans are quickly becoming a new frontline in the nationwide battle over campus expression. Barnard’s agreement follows a controversial decision earlier this year in which Columbia University agreed to ban masks at protests, among other measures, in exchange for the release of $400 million in frozen federal funding. Columbia’s move came just days after President Donald Trump declared on Truth Social that he would end federal funding for any school that “allows illegal protests,” adding: “NO MASKS!”

While some institutions like Columbia and Barnard impose strict rules prohibiting masks, policies at other colleges and universities allow face coverings to be worn unless students are violating law or school policy, or if officials ask for them to be removed.

For example, California State University’s time, place, and manner policy allows wearing masks on university property as long as students do not “attempt to hide or disguise their identity from the university official” when violating university policy. In Texas, the recently passed Senate Bill 2972 bans face coverings during protests at public colleges, undermining the state’s efforts to protect student speech rights back in 2019.

Placing a preemptive, blanket requirement on all protesters to identify themselves to college administrators — untethered to engaging in misconduct — risks discouraging students and faculty from speaking their minds. Instead of these speech-chilling bans, universities should limit their policies to seeking the identification of those who violate university policies or the law.

From the Boston Tea Party to Occupy Wall Street, protesters have historically used face coverings to protect their identities from public violence, doxxing, and retaliation from employers and government officials. More recently, using masks to avoid identification has become associated with protesters advocating for Palestinian rights. Given the threats coming from school administrations and the U.S. government, activists may feel it necessary to take precautions to avoid revealing their identities and becoming targets for their expression.

Sometimes people just want to be able to express themselves without concern for what their family, friends, the general public, or the government may think.

So why are schools and local authorities putting so much effort into banning masks? The answer is control. When people have fewer protections, they face a higher risk of being penalized for their speech. That’s a risk that many are afraid to take.

Legal and ethical backlash is building against mask bans

Politicians claim mask bans are about stopping crime. But the real effect is to make dissent more costly and dangerous — especially when tied to hot-button issues like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Officials in Nassau County, New York, for example, signed a mask ban into law in August 2024 aimed at discouraging crime and anti-Semitic acts. According to CBS News, violating the law is considered a misdemeanor punishable by a year in jail or a $1,000 fine. Critics of the ban point out that, even with religious and health-related exemptions, the new policy gives authorities the power to question anyone wearing a mask — a power that can easily be abused.

So to Speak Podcast Transcript: ‘Shouting fire,’ deepfake laws, tenured professors, and mask bans

The FIRE team discusses Tim Walz’s controversial comments on hate speech and “shouting fire in a crowded theater.” We also examine California’s AI deepfake laws, the punishment of tenured professors, and mask bans.

Read More

A lawsuit challenged the mask ban in Nassau County by contending that the law could lead to discrimination against individuals with disabilities. A judge dismissed the case a month later, ruling that the law included sufficient exemptions. However, even with health-related exemptions, there remains a risk of the law being used to silence protesters. In fact, among the first arrests made under the ordinance was an individual who was peacefully protesting while wearing a keffiyeh.

It’s no wonder there has been backlash from students and the public over these sweeping policies. In February, a student government representative at Columbia sent out a poll to students asking their opinions on campus security and the potential mask ban. The findings, published by the Columbia Spectator, showed that nearly three-quarters of respondents do not support mask bans.

Critics have been challenging the legal basis of anti-mask policies on and off campus, highlighting the possibility for discrimination and infringement on First Amendment rights. After all, masks can be used for a variety of purposes, from protecting one’s health to protesting anonymously to dressing up on Halloween. It shouldn’t be assumed that all mask-wearers intend to commit a crime. Sometimes people just want to be able to express themselves without concern for what their family, friends, the general public, or the government may think. Many uses of masks are inherently expressive. That means banning them raises constitutional concerns.

What’s the legal precedent for mask bans on campus?

The history of mask bans in the United States is complicated. The Supreme Court has never directly commented on whether banning masks during expressive activities infringes on First Amendment rights, and jurisdictions are split on the matter.

In many states, mask bans gained popularity between the 1920s and 1950s in response to actions of the Ku Klux Klan. For example, in Church of the American Knights of the Ku Klux Klan v. Kerik, KKK members challenged a New York anti-mask law when the group’s parade permit was denied because of planned mask-wearing. Despite the group’s argument that the masks were a form of expression, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that the masks worn by KKK members added “no expressive force to the message portrayed by the rest of the outfit.” Since the robes and hoods that were part of their uniforms could easily communicate to others that they were part of the Klan, the court concluded the “expressive force of the mask is, therefore, redundant.”

Similarly, in State v. Miller, another case involving the KKK, the Supreme Court of Georgia upheld a state mask ban because “the statute distinguishe[d] appropriately between mask-wearing that is intimidating, threatening or violent and mask-wearing for benign purposes.”

In contrast, in American Knights of the Ku Klux Klan v. City of Goshen, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Indiana struck down the city’s mask ban, holding the “United States Constitution protects a group’s speakers the right to anonymity when past harassment makes it likely that disclosing the members would impact the group’s ability to pursue its collective efforts at advocacy.”

Likewise, in Ghafari v. Municipal Court for San Francisco, California’s First Appellate District struck down the state’s mask law when it was used to arrest members of the Iranian Students’ Association who were peacefully protesting outside the Iranian Consulate in San Francisco. The students were covering their faces while protesting out of concern that the Iranian government would retaliate against them or their family members.

If people aren’t allowed to use tools to protect their identities when speaking out, many voices will be silenced.

While some states have deemed mask restrictions unconstitutional, others still have them in place. For example, the state of Virginia still has a law passed in the 1950s that prohibits wearing face masks in public spaces with a few exceptions for health and religious reasons.

Despite the conflicting case precedent, it is safe to say that any full mask ban with no exceptions is likely unconstitutional. This is for a variety of reasons: health concerns, religious protections, and the right to anonymous speech.

The history of constitutional protections for anonymous expression

The Supreme Court has consistently upheld the right to engage in anonymous speech. In the 1960 case Talley v. California, civil rights activist Manuel Talley was arrested and fined after distributing handbills on a sidewalk in Los Angeles. The handbills called for the boycott of merchants who carried products from manufacturers who refused to extend equal employment opportunities to racial minorities. Though the handbills included the name of the organization Talley was representing, law enforcement officers found them to be in violation of a Los Angeles City ordinance banning the distribution of handbills without an author’s name.

The Supreme Court declared the ordinance was unconstitutional, holding that it was overbroad and not narrowly tailored to its suggested purpose of “identify[ing] those responsible for fraud, false advertising and libel.” In his opinion for the Court, Justice Hugo Black stated that “[a]nonymous pamphlets, leaflets, brochures and even books have played an important role in the progress of mankind,” highlighting the importance of these works in securing American independence.

What to make of anti-mask laws and mask-required laws? — First Amendment News 429

First Amendment News is a weekly blog and newsletter about free expression issues by Ronald K. L. Collins and is editorially independent from FIRE.

Read More

Thirty-five years later in McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission, the Supreme Court upheld protections for anonymous speech when a resident of Westerville, Ohio, was fined for distributing anonymous handbills in opposition to her local school district’s request for a tax levy. Overturning Ohio’s election law that prohibited the distribution of anonymous campaign literature, the Court held that First Amendment protection for anonymous speech extends to “core political speech.” In doing so, the Court acknowledged that anonymous speech serves “to protect unpopular individuals from retaliation — and their ideas from suppression — at the hand of an intolerant society.”

Despite this precedent, higher courts haven’t really addressed the role that masks play in protecting speech in our modern world where phones and cameras are always watching. If courts want to preserve free expression, they should keep in mind the many threats that individuals face when speaking in public. If people aren’t allowed to use tools to protect their identities when speaking out, many voices will be silenced.

What does this mean for college campuses?

Since mask bans on college campuses are a newer issue, it’s unclear how courts may react. Still, we know a few things for sure. First, any public university policy must be viewpoint neutral and narrowly tailored toward achieving a specific and important government goal. Also, anti-mask policies must include exceptions for individuals with disabilities or religious customs that involve wearing face coverings.

But narrow tailoring also means universities cannot ban mask-wearing in ways that unnecessarily burden protected activity, such as anonymous protest. It is not a crime to peacefully protest while wearing a mask to avoid retaliation, and a blanket prohibition that includes such activity would raise serious constitutional issues.

That said, school can restrict masks in certain situations. For instance, schools can prohibit masks while committing crimes or violent acts, violating school rules, or engaging in unprotected speech. And if you’re breaking the law, law enforcement can absolutely ask for identification.

Is dissent the real target?

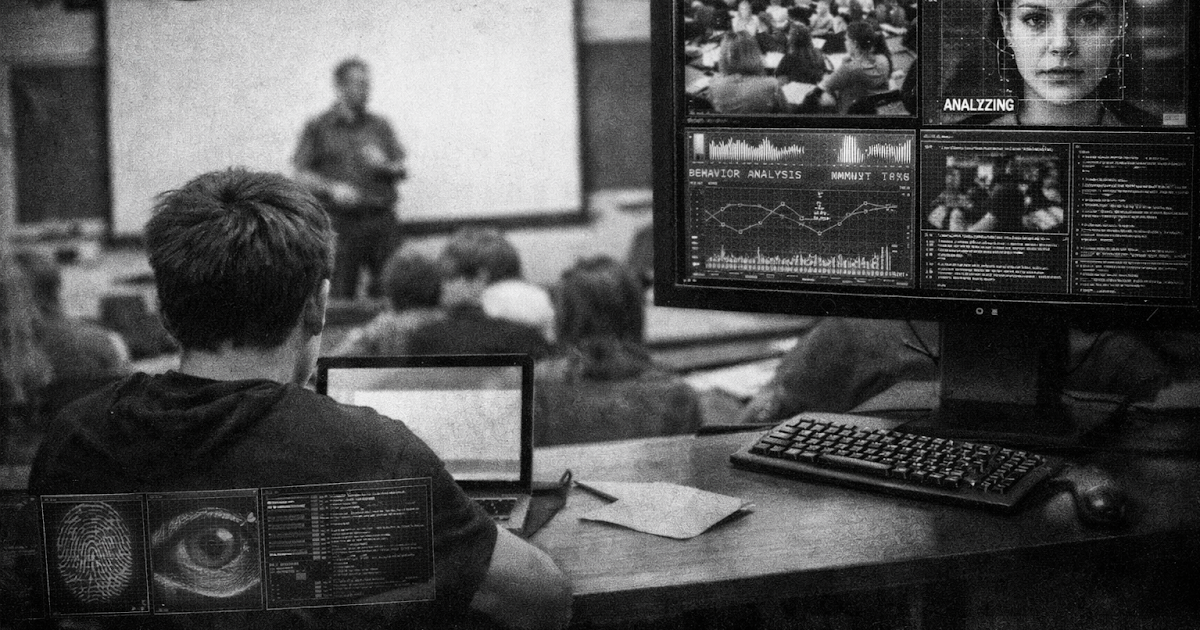

Protesting in today’s world is different than it was before. When we leave our homes, we enter a space that is always being watched — not just by individuals walking around with their phones, but also by security cameras and surveillance technology. These are serious things for modern protesters to consider, especially when having a video go viral can bring severe and disproportionate consequences, such as losing your scholarship, your job, or even your visa. In this way, mask bans empower both police and private actors to suppress dissent.

A lack of anonymity can also amplify the “chilling effect,” in which people self-censor out of concern that they will violate some type of law, regulation, or social norm. According to FIRE’s 2025 College Free Speech Rankings, the chilling effect can be a problem for students across the political spectrum, with 34% of very conservative students and 15% of very liberal students reporting that they self-censored “very” or “fairly” often.

Masks are one way of combating this problem. For example, a student who wishes to participate in a pro-life rally may be more comfortable doing so if they can wear a mask and avoid being judged or harassed by their peers. Similarly, students and faculty may feel more free to voice their concerns about their school administration if they are able to wear masks. In an interview for CNN, an anonymous Columbia student going by the name “Maria” told reporters that she would no longer be participating in protests on campus due to the new policies adopted by the university. She stated she is “staunchly aware of how militarized and surveilled [the] campus is now,” and is fearful of retaliation. With mask bans becoming increasingly popular, this will likely be a growing sentiment among students.

Masks are an important tool for dissent and expression, both on and off campus. Even if sometimes ineffective in the face of advanced technology, masks provide a last line of defense for individuals who want to peacefully engage in public expression, giving them a small but important sense of security and anonymity. With recent reports of students being arrested for merely engaging in protected speech on their campuses, it is more important than ever to defend the right to anonymous speech.