Tag: Teachers

-

NJ Teachers, Don’t Quit Your Jobs

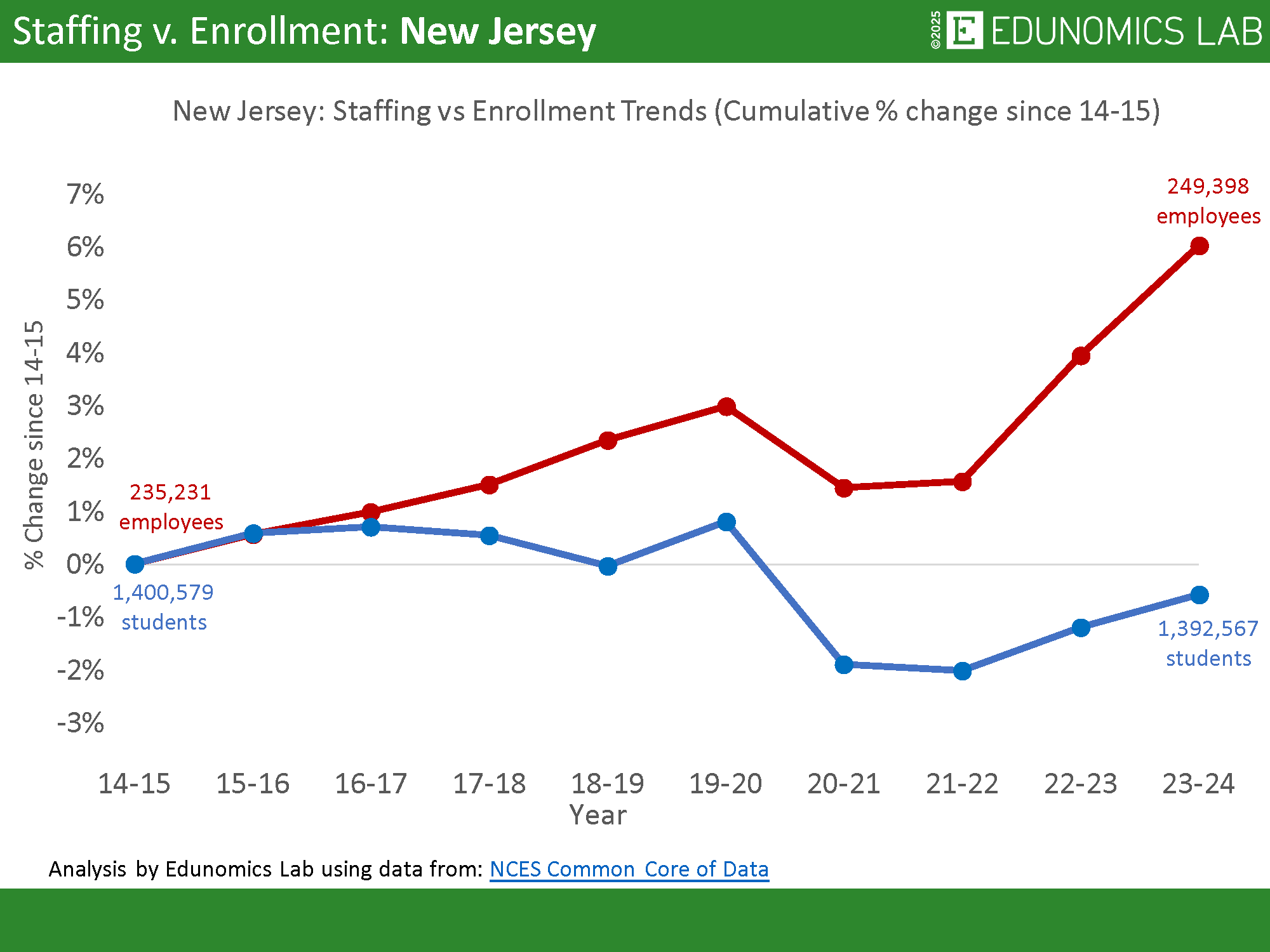

What is going on in this graph at the bottom that juxtaposes the number of New Jersey educators with the number of students enrolled in NJ school districts?

This: Over the last decade, staffing is up while enrollment is down, according to data collected by Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab. New Jersey isn’t an outlier here because the trend of increased staffing and decreased student population is happening across the country, fueled by outsized federal grants (called ESSER) to each state after the pandemic. That money was intended to ameliorate learning loss suffered by students locked out of school, a short-term infusion never intended to be baked into district payrolls.

During 2021-2024, the time period when the federal government distributed that ESSER money (total: about $2.6 billion to NJ), NJ school districts hired about 10,000 additional staff members, represented by the red line on the graph. By 2024 we employed over 249,000 educators.

But here’s the rub or, rather, two: first, we have what analysts call “the fiscal cliff” because the federal infusions dried up last year, leaving districts cash-strapped. Second, over the last decade enrollment across NJ schools is down by over 100,000 students. Since enrollment factors into our state funding formula, many districts take another budgetary hit.

Edunomics leaders Marguerite Roza and Katherine Silberstein write in the 74, “districts are paying for more employees than they can afford. To make matters worse, during the same time period, districts have been losing students. That means that state and local dollars (which tend to be driven by enrollment counts) are unlikely to make up the gap.”

What’s next?

“Right-sizing,” i.e., districts across the country will be laying off staff members because fewer students need fewer teachers and less money means less to spend on payroll.

The bad news? Some teachers will lose their jobs and districts will be facing tough math to balance budgets.

The good news? With the exception of fields STEM, special education, and multilingual learners, the teacher shortage is over.

-

How AI can fix PD for teachers

Key points:

The PD problem we know too well: A flustered woman bursts into the room, late and disoriented. She’s carrying a shawl and a laptop she doesn’t know how to use. She refers to herself as a literacy expert named Linda, but within minutes she’s asking teachers to “dance for literacy,” assigning “elbow partners,” and insisting the district already has workbooks no one’s ever seen (awalmartparkinglott, 2025). It’s chaotic. It’s exaggerated. And it’s painfully familiar.

This viral satire, originally posted on Instagram and TikTok, resonates with educators not because it’s absurd but because it mirrors the worst of professional development. Many teachers have experienced PD sessions that are disorganized, disconnected from practice, or delivered by outsiders who misunderstand the local context.

Despite decades of research on what makes professional development effective–including a focus on content, active learning, and sustained support (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Joseph, 2024)–too many sessions remain generic, compliance-driven, or disconnected from day-to-day teaching realities. Instructional coaching is powerful but costly (Kraft et al., 2018), and while collaborative learning communities show promise, they are difficult to maintain over time.

Often, the challenge is not the quality of the ideas but the systems needed to carry them forward. Leaders struggle to design relevant experiences that sustain momentum, and teachers return to classrooms without clear supports for application or follow-through. For all the time and money invested in PD, the implementation gap remains wide.

Artificial intelligence is not a replacement for thoughtful design or skilled facilitation, but it can strengthen how we plan, deliver, and sustain professional learning. From customizing agendas and differentiating materials to scaling coaching and mapping long-term growth, AI offers concrete ways to make PD more responsive and effective (Sahota, 2024; Adams & Middleton, 2024; Tan et al., 2025).

The most promising applications do not attempt one-size-fits-all fixes, but instead address persistent challenges piece by piece, enabling educators to lead smarter and more strategically.

Reducing clerical load of PD planning

Before any PD session begins, there is a quiet mountain of invisible work: drafting the description, objectives, and agenda; building slide decks; designing handouts; creating flyers; aligning materials to standards; and managing time, space, and roles. For many school leaders, this clerical load consumes hours, leaving little room for designing rich learning experiences.

AI-powered platforms can generate foundational materials in minutes. A simple prompt can produce a standards-aligned agenda, transform text into a slide deck, or create a branded flyer. Tools like Gamma and Canva streamline visual design, while bots such as the PD Workshop Planner or CK-12’s PD Session Designer tailor agendas to grade levels or instructional goals.

By shifting these repetitive tasks to automation, leaders free more time for content design, strategic alignment, and participant engagement. AI does not just save time–it restores it, enabling leaders to focus on thoughtful, human-centered professional learning.

Scaling coaching and sustained practice

Instructional coaching is impactful but expensive and time-intensive, limiting access for many teachers. Too often, PD is delivered without meaningful follow-up, and sustained impact is rarely evident.

AI can help extend the reach of coaching by aligning supports with district improvement plans, teacher and student data, or staff self-assessments. Subscription-based tools like Edthena’s AI Coach provide asynchronous, video-based feedback, allowing teachers to upload lesson recordings and receive targeted suggestions over time (Edthena, 2025). Project Café (Adams & Middleton, 2024) uses generative AI to analyze classroom videos and offer timely, data-driven feedback on instructional practices.

AI-driven simulations, virtual classrooms, and annotated student work samples (Annenberg Institute, 2024) offer scalable opportunities for teachers to practice classroom management, refine feedback strategies, and calibrate rubrics. Custom AI-powered chatbots can facilitate virtual PLCs, connecting educators to co-plan and share ideas.

A recent study introduced Novobo, an AI “mentee” that teachers train together using gestures and voice; by teaching the AI, teachers externalized and reflected on tacit skills, strengthening peer collaboration (Jiang et al., 2025). These innovations do not replace coaches but ensure continuous growth where traditional systems fall short.

Supporting long-term professional growth

Most professional development is episodic, lacking continuity, and failing to align with teachers’ evolving goals. Sahota (2024) likens AI to a GPS for professional growth, guiding educators to set long-term goals, identify skill gaps, and access learning opportunities aligned with aspirations.

AI-powered PD systems can generate individualized learning maps and recommend courses tailored to specific roles or licensure pathways (O’Connell & Baule, 2025). Machine learning algorithms can analyze a teacher’s interests, prior coursework, and broader labor market trends to develop adaptive professional learning plans (Annenberg Institute, 2024).

Yet goal setting is not enough; as Tan et al. (2025) note, many initiatives fail due to weak implementation. AI can close this gap by offering ongoing insights, personalized recommendations, and formative data that sustain growth well beyond the initial workshop.

Making virtual PD more flexible and inclusive

Virtual PD often mirrors traditional formats, forcing all participants into the same live sessions regardless of schedule, learning style, or language access.

Generative AI tools allow leaders to convert live sessions into asynchronous modules that teachers can revisit anytime. Platforms like Otter.ai can transcribe meetings, generate summaries, and tag key takeaways, enabling absent participants to catch up and multilingual staff to access translated transcripts.

AI can adapt materials for different reading levels, offer language translations, and customize pacing to fit individual schedules, ensuring PD is rigorous yet accessible.

Improving feedback and evaluation

Professional development is too often evaluated based on attendance or satisfaction surveys, with little attention to implementation or student outcomes. Many well-intentioned initiatives fail due to insufficient follow-through and weak support (Carney & Pizzuto, 2024).

Guskey’s (2000) five levels of evaluation, from initial reaction to student impact, remain a powerful framework. AI enhances this approach by automating assessments, generating surveys, and analyzing responses to surface themes and gaps. In PLCs, AI can support educators with item analysis and student work review, offering insights that guide instructional adjustments and build evidence-informed PD systems.

Getting started: Practical moves for school leaders

School leaders can integrate AI by starting small: use PD Workshop Planner, Gamma, or Canva to streamline agenda design; make sessions more inclusive with Otter.ai; pilot AI coaching tools to extend feedback between sessions; and apply Guskey’s framework with AI analysis to strengthen implementation.

These actions shift focus from clerical work to instructional impact.

Ethical use, equity, and privacy considerations

While AI offers promise, risks must be addressed. Financial and infrastructure disparities can widen the digital divide, leaving under-resourced schools unable to access these tools (Center on Reinventing Public Education, 2024).

Issues of data privacy and ethical use are critical: who owns performance data, how it is stored, and how it is used for decision-making must be clear. Language translation and AI-generated feedback require caution, as cultural nuance and professional judgment cannot be replicated by algorithms.

Over-reliance on automation risks diminishing teacher agency and relational aspects of growth. Responsible AI integration demands transparency, equitable access, and safeguards that protect educators and communities.

Conclusion: Smarter PD is within reach

Teachers deserve professional learning that respects their time, builds on their expertise, and leads to lasting instructional improvement. By addressing design and implementation challenges that have plagued PD for decades, AI provides a pathway to better, not just different, professional learning.

Leaders need not overhaul systems overnight; piloting small, strategic AI applications can signal a shift toward valuing time, relevance, and real implementation. Smarter, more human-centered PD is within reach if we build it intentionally and ethically.

References

Adams, D., & Middleton, A. (2024, May 7). AI tool shows teachers what they do in the classroom—and how to do it better. The 74. https://www.the74million.org/article/opinion-ai-tool-shows-teachers-what-they-do-in-the-classroom-and-how-to-do-it-better

Annenberg Institute. (2024). AI in professional learning: Navigating opportunities and challenges for educators. Brown University. https://annenberg.brown.edu/sites/default/files/AI%20in%20Professional%20Learning.pdf

awalmartparkinglott. (2025, August 5). The PD presenter that makes 4x your salary [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/reel/DMGrbUsPbnO/

Carney, S., & Pizzuto, D. (2024). Implement with IMPACT: A framework for making your PD stick. Learning Forward Publishing.

Center on Reinventing Public Education. (2024, June 12). AI is coming to U.S. classrooms, but who will benefit? https://crpe.org/ai-is-coming-to-u-s-classrooms-but-who-will-benefit/

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Effective_Teacher_Professional_Development_REPORT.pdf

Edthena. (2025). AI Coach for teachers. https://www.edthena.com/ai-coach-for-teachers/

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin Press.

Jiang, J., Huang, K., Martinez-Maldonado, R., Zeng, H., Gong, D., & An, P. (2025, May 29). Novobo: Supporting teachers’ peer learning of instructional gestures by teaching a mentee AI-agent together [Preprint]. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.17557

Joseph, B. (2024, October). It takes a village to design the best professional development. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-it-takes-a-village-to-design-the-best-professional-development/2024/10

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318759268

O’Connell, J., & Baule, S. (2025, January 17). Harnessing generative AI to revolutionize educator growth. eSchool News. https://www.eschoolnews.com/digital-learning/2025/01/17/generative-ai-teacher-professional-development/

Sahota, N. (2024, July 25). AI energizes your career path & charts your professional growth plan. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilsahota/2024/07/25/ai-energizes-your-career-path–charts-your-professional-growth-plan/

Tan, X., Cheng, G., & Ling, M. H. (2025). Artificial intelligence in teaching and teacher professional development: A systematic review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2024.100355

Latest posts by eSchool Media Contributors (see all) -

Overrepresentation of female teachers and gender differences in PISA 2022: what cross-national evidence can and cannot tell us

Over the weekend HEPI published blogs on AI in legal education and knowledge and skills in higher education.

Today’s blog was kindly authored by Hans Luyten, University of Twente, Netherlands ([email protected]).

Across many education systems, secondary-school teaching remains a predominantly female profession. While this fact is well known, less is understood about whether the gender composition of the teaching workforce relates to gender differences in student achievement at the system level. My recently published paper, Overrepresentation of Female Teachers in Secondary Education and Gender Achievement Gaps in PISA 2022 (Studies in Educational Evaluation), takes up this question using recent international data.

The study investigates whether gender differences in reading, mathematics, and science among 15-year-olds vary according to the extent to which women are overrepresented among secondary-school teachers, relative to their share in each country’s labour force.

Data and analytical approach

The analysis draws on two international datasets:

- PISA 2022: Providing country-level average scores for 15-year-olds in reading, mathematics, and science. Gender achievement gaps are operationalised as the difference between the average score for girls and that for boys.

- Labour-market data: Measuring the proportion of women among secondary-school teachers in each country and the proportion of women in the wider labour force.

Female overrepresentation is defined as the difference between these two proportions.

Although the analysis focuses on statistical correlations at the country level, it does not rely on simple bivariate associations. A wide range of control variables is included to account for differences between countries in:

- Students’ out-of-school lives, such as gender differences in family support;

- School resources, such as the availability of computers;

- School staff characteristics, such as the percentage of certified teachers.

These controls help ensure that the observed relationships are not simply reflections of broader cross-national differences in socioeconomic conditions or school quality.

Key findings

Three main results emerge from the analysis:

First, gender achievement gaps tend to be larger in favour of girls in countries where women are more strongly overrepresented among secondary-school teachers.

Second, this association holds across all three domains (reading, mathematics, and science), although the size and direction of the gender gap differs by subject.

Third, the relationship becomes more pronounced as the degree of female overrepresentation increases. Countries with only modest overrepresentation tend to have smaller gender gaps, whereas those with large overrepresentation tend to have wider gaps.

These findings concern gender differences in performance, not the absolute levels of boys’ or girls’ achievement. The study does not examine, and therefore does not draw conclusions about, whether boys or girls perform better or worse in absolute terms in countries with different levels of female teacher overrepresentation.

Interpreting the results

The analysis identifies a robust statistical association at the country level, after accounting for a broad set of background variables. However, as with any cross-national correlational study, it cannot establish causality. Other country-specific characteristics (cultural, institutional, or organisational) may also contribute to the observed patterns.

It is also important to note that the study addresses a different question from research that examines the effects of individual teachers’ gender on the achievement of individual students. Earlier classroom- and school-level studies often find little or no systematic effect of teacher gender on student outcomes. The present study, by contrast, examines the overall gender composition of the teaching workforce and its relation to system-level gender achievement gaps.

Implications

Although the findings do not directly point to specific policy interventions, they suggest that the gender composition of the secondary-school teaching workforce is a feature of educational systems that merits closer attention when interpreting international variation in gender gaps. Teacher demographics form part of the broader context within which student achievement develops, and system-level gender imbalances may interact with other structural characteristics in shaping performance differences between girls and boys.

Final remarks

The full paper provides a detailed description of the data, analyses, and limitations. It is available open access at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2025.101544

I hope this summary brings the findings to a wider audience and encourages further research on how system-level characteristics relate to gender differences in educational outcomes.

-

Child care workers are building a network of resistance against Immigration and Customs Enforcement

This story was produced by The 19th and reprinted with permission.

The mother was just arriving to pick up her girls at their elementary school in Chicago when someone with a bullhorn at the nearby shopping center let everyone know: ICE is here.

The white van screeched to a halt right next to where she was parked, and three Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents piled out. They said something in English that she couldn’t decipher, then arrested her on the spot. Her family later said they never asked about her documentation.

She was only able to get one phone call out before she was taken away. “The girls,” was all she said to her sister. Her daughters, a third grader and a fourth grader, were still waiting for her inside the school.

Luckily, the girls’ child care provider had prepared for this very moment.

Sandra had been taking care of the girls since they were babies, and now watched them after school. She’d been encouraging the family to get American passports for the kids and signed documents detailing their wishes should the mother be detained.

When Sandra got the call that day in September, she headed straight to the school to pick up the girls.

Since President Donald Trump won a second term, Sandra has been prepping the 10 families at her home-based day care, including some who lack permanent legal status, for the possibility that they may be detained. (The 19th is only using Sandra’s first name and not naming the mother to protect their identities.)

She’s worked with families to get temporary guardianship papers sorted and put a plan in place in case they were detained and their kids were left behind. She even had a psychologist come and speak to the families about the events that had been unfolding across the country to help the children understand that there are certain situations their parents can’t control, and give them the opportunity to talk through their fears that, one day, mamá and papá might not be there to pick them up.

And for two elementary school kids, that day did come. Sandra met them outside the school.

“When they saw me, they knew something wasn’t right,” Sandra said in Spanish. “Are we never going to see our mom again?” they asked.

For all her planning, she was speechless.

“One prepares for these things, but still doesn’t have the words on what to say,” Sandra said.

Related: Young children have unique needs and providing the right care can be a challenge. Our free early childhood education newsletter tracks the issues.

After that day, Sandra worked with the mother’s sister to get the girls situated to fly to Texas, where their mother, who had full custody of them, was being detained, and then eventually to Mexico. She hasn’t heard from them in over a month. The girls were born in the United States and know nothing of Mexico.

“I think about them in a strange country,” Sandra said. “‘Who is going to care for them like I do?’ Now with this situation I get sad because I think they are the ones who are going to suffer.”

In this year of immigration raids, child care providers have stepped up to keep families unified amid incredible uncertainty. Some are agreeing to be temporary guardians for kids should something happen to their parents. The workers themselves are also under threat — 1 in 5 child care workers are immigrant women, most of them Latinas, who are also having to prepare in case they are detained, particularly while children are in their care. Already, child care workers across the country have been detained and deported.

“The immigration and the child care movements, they are one in the same now,” said Anali Alegria, the director of federal advocacy and media relations at the Child Care for Every Family Network, a national child care advocacy group. “Child care is not just something that keeps the economy going, while it does. It’s also really integral to people’s community and family lives. And so when you’re destabilizing it, you’re also destabilizing something much more fundamental and very tender to that child and that family’s life.”

A loose network of resistance has emerged, with detailed protection plans, ICE lookout patrols, and Signal or Whatsapp chats. Home-based providers like Sandra have been especially involved in that effort because their work often means their lives are even more intertwined with the families they care for.

“All the families we have in our program, I consider them family. We arrive in this country and we don’t have family, and when we get support, advice or the simple act of caring for kids, as child care providers we are essential in many of these families — even more in these times,” said Sandra, who has been caring for children in the United States for 25 years. All the families she cares for are Latinx, 70 percent without permanent legal status.

Related: 1 in 5 child care workers is an immigrant. Trump’s deportations and raids have many terrified

According to advocacy groups, child care providers are increasingly being asked to look after kids in case they are detained, typically because they are the only trusted person the family knows with U.S. citizenship or legal permanent residence. Parents are asking child care workers to be emergency contacts, short-term guardians and, in some cases, even long-term guardians.

“We heard this under the first Trump administration, and we’re hearing it much more now. It’s not so much a matter of if, but when, right now, and it used to be the other way around,” said Wendy Cervantes, the director of immigration and immigrant families at the Center for Law and Social Policy, an anti-poverty nonprofit. “It adds just additional stress and trauma because they deeply care about these kids. Many of them have kids of their own and obviously have modest incomes, so as much as they want to say, ‘yes’, they can’t in some cases.”

The question was posed to Claudia Pellecer a couple weeks ago. A home-based child care provider in Chicago for 17 years, Pellecer cares for numerous Latinx families, at least one of whom doesn’t have permanent legal status.

In October, one of those moms was due to appear before ICE for a regular check-in as part of her ongoing asylum case. But she knew that many have been detained at those appointments this year.

The mother asked Pellecer to be her 1-year-old son’s legal guardian should she be taken away.

“I couldn’t say no because I am human, I am a mother,” Pellecer said.

Claudia Pellecer, who runs a small daycare for young children out of her home, stands for a portrait outside her house. Credit: Jamie Kelter Davis for The 19th They got to work getting the baby a passport and filling out the necessary guardianship paperwork. Pellecer kept the originals and copies. The mother closed her bank account, cleaned out her apartment and prepped two bags, one for her and one for the baby. If the mother was deported, Pellecer would fly with him to meet her in Ecuador, they agreed.

The day of the appointment, she dropped the baby off with Pellecer and set the final plan. Her appointment was at 1 p.m. “If at 6 p.m. you haven’t heard from me, that means I was detained,” she told Pellecer, who cried and wished her luck.

At the appointment, the judge asked her three sets of questions:

“Why are you here?”

“Are you working? Do you have a family?”

“Do you have proof of what happened to you in your country?”

Related: Child care centers were off limit to immigration authorities. How that’s changed

Claudia Pellecer plays games with children in the living room of her home daycare, where she cares for up to eight young children a day. Credit: Jamie Kelter Davis for The 19th The judge agreed to let her stay and told her to continue working. The mother won’t have a court date again until 2027.

“We learned our lesson,” Pellecer said. “We had to prepare for the worst and hope for the best.”

But their relief was short-lived. Recent events in Chicago have sent child care workers and families into panic, as the people who have tried to keep families together are now being targeted.

Resistance networks have sprung up rapidly in Chicago in recent weeks after a child care worker was followed to Spanish immersion day care Rayito de Sol on the city’s North Side and arrested in front of children and other teachers. The arrest was caught on camera and has sparked demonstrations across the city.

Erin Horetski, whose son, Harrison, was cared for by the worker who was arrested at Rayito de Sol in early November, said parents there had been worried ICE might one day target them because the center specifically hired Spanish-speaking staff.

The morning of the arrest, parents were texting each other once they heard ICE was in the shopping center where the day care is located.

Children crawl on a colorful rug while playing educational games at Claudia Pellecer’s home daycare. Credit: Jamie Kelter Davis for The 19th Her husband was just arriving to drop off their boys as ICE was leaving. The first thing out of his mouth when he called her: “They took Miss Diana.”

Agents entered the school without a warrant to arrest infant class teacher Diana Patricia Santillana Galeano, an immigrant from Colombia. DHS said part of the reason for her arrest was because she helped bring her two teenage children across the southern U.S. border this year. “Facilitating human smuggling is a crime,” DHS said. Santillana Galeano fled Colombia fearing for her safety in 2023, filed for asylum and was given a work permit through November 2029, according to court documents. She has no known criminal record. After her arrest, a federal judge ruled that her detention without access to a bond hearing was illegal and she was released November 12.

Horetski said the incident, the first known ICE arrest inside a day care, has spurred the community to action. A GoFundMe account set up by Horetski to support Santillana Galeano, has raised more than $150,000.

Horetski said what’s been lost in the story of what happened at Rayito is the humanity of the person at the center of it, someone she said was “like a second mother” to her son.

“At the end of the day, she was a person and a friend and a mother and provider to our kids — I think we need to remember that,” Horetski said.

Related: They crossed the border for better schools. Now, some families are leaving the US

Now, the parents are the ones coming together to put in place a safety plan for the teachers, most of whom have continued to come to the school and care for their children.

They are working on establishing a safe passage patrol, setting up parents with whistles at the front of the school to stand guard during arrival and dismissal time to ensure teachers can come and go to their cars or to public transit safely. Parents are also establishing escorts for teachers who may need a ride to work or someone to accompany them on the bus or the train. A meal train set up by the parents is helping to send food to the teachers through Thanksgiving, and two local restaurants have pitched in with discounts. Some of the parents are also lawyers who are considering setting up a legal clinic to ensure workers know their rights, Horetski said.

A young child watches an educational TV show in the living room of Claudia Pellecer’s home daycare in Chicago. Credit: Jamie Kelter Davis for The 19th Figuring out how to come together to support teachers and the children who now have questions about safety is something that “continues to circle in all of our minds and brains,” Horeski said. “It’s hard to not have the answers or know how to best move forward. We’re in such uncharted territory that you’re like, ‘Where do you go from here?’ So we’re kind of paving that because this is the first time that something like this has happened.”

Prep is top of mind now for organizers including at the Service Employees International Union, where Sandra and Pellecer are members, who are convening emergency child care worker trainings to set up procedures, such as posted signs that say ICE cannot enter without a warrant, showing them what the warrants must include to be binding, helping them set a designated person to speak to ICE should they enter and talking to their families to offer support.

Cervantes has been doing this work since Trump’s first term, when it was clear immigration was going to be a key focus for the president. This year has been different, though. Child care centers were previously protected under a “sensitive locations” directive that advised ICE to not conduct enforcement in places like schools and day cares. But Trump removed that protection on his first day in office this year, signaling a more aggressive approach to ICE enforcement was coming.

Cervantes and her team are currently in the midst of a research project about child care workers across the country, conversations that are also illuminating for them just how dire the situation has become for providers.

“We are asking providers to make protocols for what is basically a man-made disaster,” she said. “They shouldn’t have to worry about protecting children and staff from the government.”