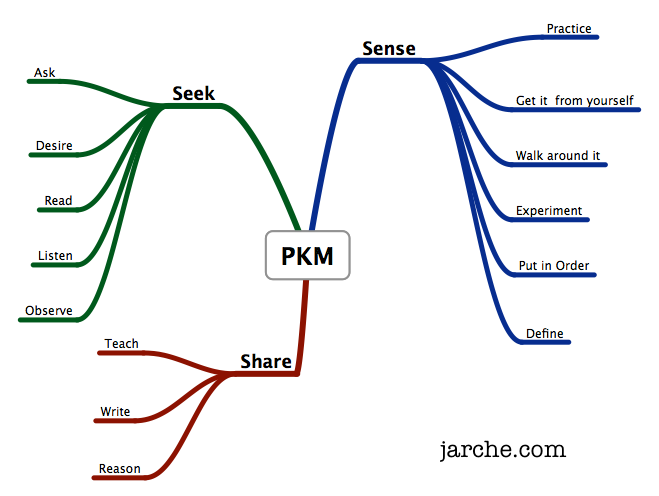

This post is one of many, related to my participation in Harold Jarche’s Personal Knowledge Mastery workshop.

I love to walk. Sometimes I do it alone (almost always listening to either music or podcasts), though most often walks these days are facilitated by an invitation from one of our kids to go for an evening walk. I’m at the POD25 conference, so have been missing my night time walks. Right now, I’m holed up in my hotel room, doing some reflecting, writing, and a bit of grading.

Instead of feeling guilty, I’m overwhelmed with supportive messages about how healthy this is. First, let’s start with walking. Rebecca Solnit writes in Wanderlust: A History of Walking about this practice:

Thinking is generally thought of as doing nothing in a production-oriented society — and doing nothing is hard to do. It’s best done by disguising it as doing something, and the something closest to doing nothing is walking.

The pull to keep producing and soaking in every bit of ROI from my university paying for this trip is strong (not because of them, I should say, but because of my own sense of needing to “get the most out of limited budget dollars”). Yet, learning cannot be perfectly quantified in terms of financial metrics, despite corporations’ and governments’ strong desire to do so. Jarche reminds us of the importance of leaving room for time and context to enrich our learning.

We cannot tap into our innovative capacities without being open to radical departures from the predictable, planned path (an example of which might be the typical professional conference schedule). And yes, sometimes that means not engaging in every planned session at a conference, like the one I’m participating in this week.

Jarche writes:

Creative work is not routine work done faster. It’s a whole different way of work, and a critical part is letting the brain do what it does best — come up with ideas. Without time for reflection, most of those ideas will get buried in the detritus of modern workplace busyness.

As we wrap up our time together, Jarche invites those of us participating in his Personal Knowledge Mastery workshop to reflect on our experience these past six weeks. Here I go, in responding to his questions:

Q. What was the most useful concept I learned from this workshop?

A. It wasn’t really a concept, rather a practice. I benefitted by committing to a regular writing practice throughout the workshop, which provided opportunities for rich reflection and deepened learning. The structure of the workshop allowed for that to take place (plus me being a person who is a bit of a completist and wanting to blog through all 18 of the opportunities for reflection and activity that Harold provided).

Q. What was the most surprising concept that has changed my thinking about PKM?

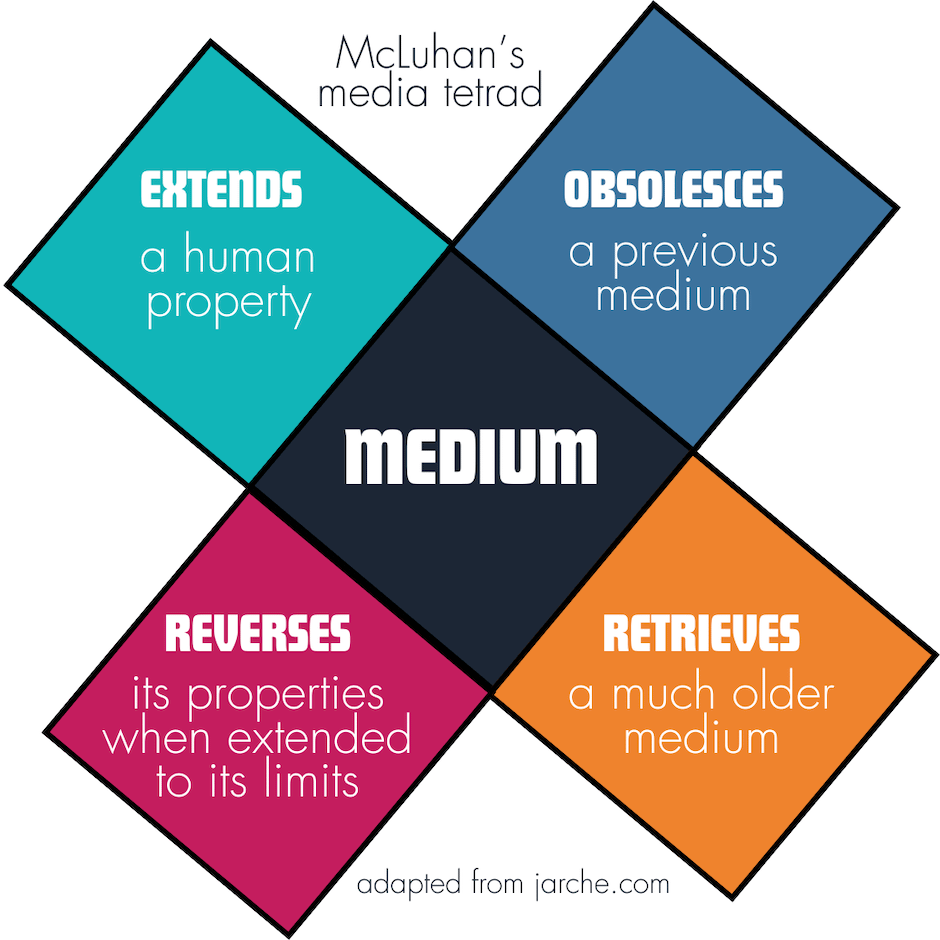

A. I had seen Jarche write about McLuhan’s media tetrad in the past, but didn’t slow myself down enough to absorb much of anything, at the time. However, given my commitment to practice PKM throughout this experience, I wrote about the concept for the first time, and even shared the framework as a part of a keynote I gave a month or so ago.

During the keynote, I couldn’t remember the word “tetrad,” when the idea came up later in the talk (as in after the slide had long since disappeared). I had attempted to come up with a word association on the plane ride out to Michigan, but it had failed me, in that moment.

“Think of the old arcade game, Tetris, plus something being “rad” (like in the 80s)”, I told myself. I was definitely learning out loud and performing retrieval practice in real time, as I eventually cobbled together audience participation input and finally got myself there.

A few things I’ve learned about myself, cognitive science, and other human beings remind me of these principles. For starters, my embarrassment in not knowing, but still struggling through and reaching the side of knowing means I’m unlikely to forget the word in the future. Plus, people aren’t looking for other humans to be perfect. It is through our vulnerability and relatability that we might most often have an opportunity to make an impact on others. At least I believe that may be the case for me… as I wasn’t meant to be the expert, as my primary role in this world, I don’t think. I would rather be known as someone who is curios, which I’ve heard enough times to start to believe that it is true.

Q. What will be the most challenging aspect of PKM for me?

A. I still need to learn more about the concepts and frameworks involving navigating complexity, including one I’ve come across in the past, but never got much further than confusion, previously: cynefin. Jim Luke (who I met a gazillion years ago at an OpenEd conference) has offered to share his wisdom about cynefin with Kate Bowles and I sometime in the next couple of months. He replied to me on Mastodon about cynefin:

I find it a very useful heuristic in thinking about community, higher ed, any activities that are organized and care-centered, etc.

This exchange wouldn’t have occurred, had it not been for Harold structuring the PKM workshop around engaging on Mastodon, by the way. This is going to be a gift that keeps on giving, I believe. While my connections there are still small in number, they are strong with competence, care, and creativity.

I’m glad that I can now pronounce cynefin without first locating an audio clip of someone else saying it. I’m useless at phonetic spelling, so that stuff doesn’t often help me in the slightest. I do still have to look up how to spell it each time. My brain feels slower with the learning when a word is pronounced differently than it is spelled. I still have to occasionally slow myself way down when spelling my own last name, so I won’t let myself feel too bad about still not being able to spell cynefin without help.

Q. Where do I hope to be with my PKM practice one year from now?

A. I would like to be in a more regular practice of blogging a year from now. I tend to save up blog post ideas that are super laborious for me (at least the way I approach the task, in those cases). I like doing posts for Jane Hart’s Top Tools 4 Learning votes (like my top ten votes from 2025). But given how extensively I write and link in those posts, they take many hours to complete. I also have enjoyed doing top podcast posts, drawing inspiration from Bryan Alexander’s wonderful posts, like this one about the podcasts he was listening to in late 2024.

My post from late 2024 about what Overcast told me I had listened to the most that year was less time consuming to write, than ones I had done in the past. But I felt weird only going from the total minutes listened as my barometer, when I think that other podcasts are far more worthy of acknowledgement than some of the ones I wound up having listened to the most that year. This 2021 Podcast Favorites post took forever to write and curate, but is more emblematic of the ways I would most like to celebrate all the incredible podcasts that are out there (or at least were publishing, at the time I wrote it).

If I put some creative constraints on myself, in terms of the time I would allow myself to commit to any individual post, I suspect I would have a lot more success with this aspect of PKM. I so appreciate the way that Alan Levine, Maha Bali, and Kate Bowles write in more reflective, informal ways. I’ve been pushing myself throughout this workshop to just get the ideas I’m having in the moment out there, to tell stories that are snapshots of my sensemaking processes, and to be human and allow myself to show up in the messiness that is indicative of the learning process.

Gratitude

My deepest gratitude goes to Harold Jarche for such a well-designed, impactful learning experience through his Personal Knowledge Mastery workshop. I had been telling myself that I would do it at some point for years, now, and finally realized that there wasn’t really ever going to be a “good time” for there to be six weeks without something big happening (conferences, speaking gigs, etc.). So Harold has been able to travel with me on airplanes, sat with me in airports, and is currently in my hotel room in San Diego at the POD 2025 conference. This is only metaphorically speaking, of course. As far as I know, he is in Canada right now. Though I am not surveilling him and he does seem to travel a lot, at least as it compares to me.

I’m also feeling thanks for those people who allow themselves to learn out loud and take the risks of being openly curious and worrying less about being “right” or “perfect” all the time.

]

]