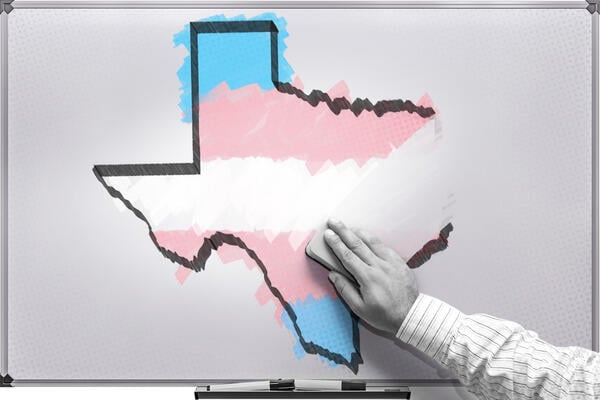

In 2023, Texas became one of the first red states to institute a sweeping ban on diversity, equity and inclusion in public colleges and universities.

Following pro-Palestinian protests and a police crackdown on an encampment at the University of Texas at Austin in 2024, the Texas Legislature this year passed another law restricting free speech on public campuses, including banning all expressive activities from 10 p.m. to 8 a.m.

The Legislature also this year passed a wide-ranging bill that allows public college and university presidents to take over faculty senates and councils, prohibits faculty elected to those bodies from serving more than two years in a row, and creates an “ombudsman” position that can threaten universities’ funding if they don’t follow that law or the DEI ban.

The lead author listed on all three laws is Sen. Brandon Creighton, chair of the Texas Senate education committee. Having overhauled higher ed statewide, he’s about to get the chance to further his vision at one large university system: On Thursday, the Texas Tech University System plans to name Creighton the “sole finalist” for the system chancellor and chief executive officer job.

His hiring by the system’s Board of Regents—whose members are appointed by the governor with confirmation from the Senate—marks another example of a Republican politician in a large red state, namely Texas and Florida, being installed as a higher ed leader. The trend reflects an evolution in how Republicans are influencing public universities, from passing laws to directly leading institutions and systems. For universities, having a former member of the Legislature in the presidency can help with lobbying lawmakers, but it could also threaten academic freedom and risk alienating faculty.

Creighton wasn’t the only, or even the highest-ranking, politician considered for the position, which historically pays more than $1 million a year. As The Texas Tribune earlier reported, Rep. Jodey Arrington, chair of the U.S. House Budget Committee and shepherd of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which affected higher ed nationwide, was also in the running. Unlike Creighton, Arrington has worked in higher ed—specifically as a vice chancellor and chancellor’s chief of staff in the Texas Tech system. Arrington, who didn’t provide Inside Higher Ed an interview, issued a statement Sunday congratulating Creighton.

Faculty leaders offered a muted response to Creighton’s impending appointment. Neither the president of the Faculty Senate at the main Texas Tech campus, the president of the university’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors nor the state AAUP conference publicly denounced Creighton. In an emailed statement, the state conference said, “We have concerns about the future of academic freedom and shared governance in the Texas Tech University System given the positions Sen. Creighton has taken in the legislature.”

“We hope that Texas Tech’s strong tradition of shared governance and academic freedom continues so that Texas Tech can thrive,” the statement said.

Cody Campbell, the system board chair, said Creighton is “a fantastic fit with our culture and is clearly the best person for the job.” He added that he likes the higher ed legislation Creighton has passed. (Creighton was also lead author of a new law that lets universities pay athletes directly.)

“He shares the values of the Texas Tech University System,” Campbell said. Both the system and the wider community of Lubbock, where the main Texas Tech campus is located, are “conservative,” he said.

“We do not subscribe to the ideas around DEI and are supportive of a merit-based culture,” Campbell said, adding that Creighton is well positioned to continue the system’s growth in research, enrollment and academic standing.

For Creighton, the job could come with a big payout. Retiring Texas Tech system chancellor Tedd L. Mitchell made $1.3 million in 2023, ranking him the 12th-highest-paid public university leader in the country, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education’s database. The system didn’t respond to Inside Higher Ed’s open records request for Mitchell’s current contract in time for this article’s publication, and Campbell told Inside Higher Ed Creighton’s pay is “yet to be determined.”

“The contract or the compensation were never part of the discussion with any of the candidates,” Campbell said.

Creighton didn’t provide Inside Higher Ed an interview or answer written questions. But he appeared to accept the position in a post on X.

“Over the past six years, no university system in Texas has taken more bold steps forward,” he wrote. “Serving as Chairman of the Senate Education Committee and the Budget Subcommittee has been the honor of a lifetime—especially to help deliver that success for Texas Tech and its regional universities. I feel very blessed to have been considered for the role of Chancellor. There is no greater purpose I would consider than working to make generational changes that transform the lives of young Texans for decades to come.”

Cowing Faculty Senates

Campbell said he doesn’t recall whether Creighton and Arrington initially expressed interest in the position to the board or whether the board reached out to them. Dustin Womble, the board’s vice chair, declined to comment. Campbell said the board “actively recruited” some candidates.

“There wasn’t really a formal application process, necessarily,” he said. But dozens of candidates across the country expressed interest in the “high-paying position” leading a large system, he said.

The system says it has more than 60,000 students across five institutions and 20 locations, including one in San José, Costa Rica. The five institutions are Texas Tech (which has multiple campuses), Texas Tech Health Sciences Center (which also has multiple campuses), the separate Texas Tech Health Sciences Center El Paso, Angelo State University and Midwestern State University.

Asked about Creighton’s lack of higher ed work experience, Campbell said that wasn’t unusual for system chancellors, contrasting the position with those of the presidents who lead individual institutions on a day-to-day basis.

“Our past chancellor was a medical doctor, the chancellor before him was a state senator, the chancellor before him was a former U.S. congressman and a state politician; we’ve had businessmen in that position, we’ve had all different types of people,” Campbell said.

Aside from serving in the Senate for a decade and the state House for seven years before that, Creighton is an attorney.

Andrew Martin, the tenured art professor who leads the Texas Tech University main campus’s AAUP chapter, noted that “our chapter has actively opposed some of the legislation that Sen. Creighton has authored.”

“Our hope now is that Sen. Creighton, in apparently assuming the role of chancellor, will spend time learning more about the campuses in the TTU System and will meet as many students, faculty [and] administrators on our campuses as possible to see how these institutions actually operate day in and day out,” Martin said. “I’m not sure how clear that’s been from his perspective as a lawyer and legislator.”

Martin—who stressed that he was speaking for himself and colleagues he’s spoken to, but not on behalf of his university—said the AAUP is concerned with maintaining academic freedom for faculty and students, upholding tenure protections, and preserving the faculty’s role in determining curriculum, conducting research and exercising shared governance.

When the Legislature passed Senate Bill 37—the Creighton legislation that, among other things, upended faculty senates—Creighton issued a news release saying, “Faculty Senates will no longer control our campuses.” He said his legislation “takes on politically charged academic programs and ensures students graduate with degrees of value, not degrees rooted in activism and political indoctrination.”

Among other things, SB 37 requires university presidents to choose who leads faculty senates. Ryan Cassidy, a tenured associate librarian, was elected to lead the Texas Tech University main campus’s Faculty Senate before SB 37 took effect, and the institution’s president has allowed him to stay in that role.

Asked about Creighton being named chancellor, Cassidy said, “I haven’t really had time to reflect on it.”

Creighton’s bio on the Legislature’s website touts his conservative values outside of higher ed, too. “He has relentlessly hammered excessive taxation, pursued ‘loser pays’ tort reform, passed drug testing for unemployment benefits, stood up for Texas’ 10th Amendment rights and effectively blocked Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion,” the bio says.

Martin said Texas Tech aspires to become a member of the Association of American Universities, a prestigious group of top research universities, of which UT Austin and Texas A&M University are already members. That would be hard if faculty are “marginalized,” he said.

“You can’t get there without the huge investment of faculty,” he said.