Texas State Employees Union

“I responded, ‘No, it’s OK, I’m aware. Let’s just ignore it. Let’s not give it any air,’” Alter said about the infiltrator’s doxing campaign. Then the texter followed up with a link to a statement from Texas State president Kelly Damphousse, posted to the university website and on Facebook, “announcing my termination for ‘inciting violence,’ effective immediately,” Alter said.

A few years ago, this story—a tenured professor fired publicly without notice or due process for asking a rhetorical question during an unaffiliated talk—would have dominated the higher education news cycle for weeks. In fact, it was such a rare occurrence that the names of those removed for similar speech incidents gained legendary status in academic circles. In 2014, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, under pressure from major donors, revoked a tenure offer to American Indian studies professor Steven Salaita because of his tweets criticizing Israel and its actions in Gaza. The scandal generated news coverage and commentary for years. Similarly, following a coordinated campaign led by law professor Alan Dershowitz, political scientist and Holocaust researcher Norman Finkelstein was denied tenure at DePaul University despite votes in favor from the department and the college. Finkelstein resigned soon after.

But Alter’s story was quickly overshadowed by a bigger one: He was fired the same day that conservative commentator Charlie Kirk was shot and killed during a campus event at Utah Valley University, sparking a more dramatic wave of faculty removals. Like many Americans, faculty took to social media to voice their opinions on Kirk. Under pressure from right-wing politicians and online activists, universities in conservative states responded with academic Jedburgh justice: punish first, ask questions later.

Michael Rex, an English and creative writing professor at Cumberland University in Tennessee, was dismissed for a post about Kirk that said, “kharma [sic] is a beautiful bitch.” Anna Kenney, an associate professor of pediatrics at Emory University in Georgia, was also terminated after calling Kirk a “disgusting individual” online. Karen Leader, an associate professor of art history at Florida Atlantic University, was put on administrative leave and investigated for months after sharing several X posts about Kirk’s public comments alongside the tag line, “This was Charlie Kirk.”

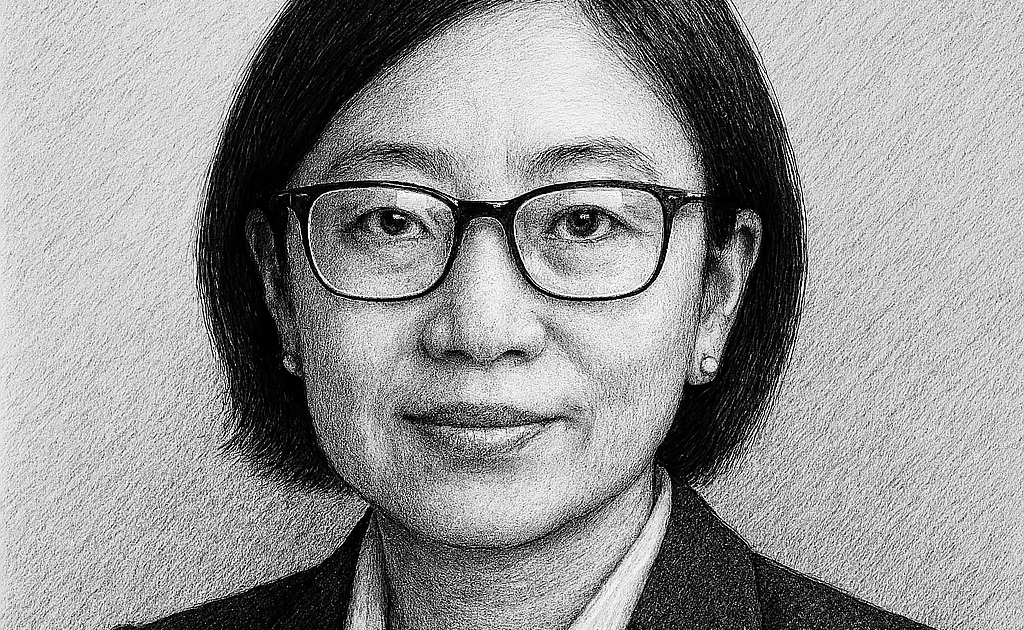

Tenure was of little help. One of the most unusual and coveted perks of an academic career, tenure historically has come with two key benefits: job security and protection from dismissal or discipline over unpopular ideas, said Deepa Das Acevedo, a legal anthropologist and tenure researcher at Emory University. But the speed and ease with which universities dismissed their faculty for personal speech exposed the tenure system’s corroded foundation, worn away by years of encroaching state policies, administrative leadership changes and a cultural shift in how the American public thinks about academia. Now faculty are left to wonder: Has the drastic politicization of the country, combined with the Trump administration’s relentless attacks on higher ed, rendered tenure moot?

To understand how September’s swift firings became possible, we must start in Wisconsin.

Sean Rayford/Getty Images

States Challenge the Academy

In 2014, then–Wisconsin governor Scott Walker challenged the “Wisconsin Idea,” the state’s century-old philosophy that all citizens should benefit from knowledge produced by the university system and that “basic to every purpose of the system is the search for truth.” He wanted the university to orient its mission toward meeting the state’s workforce needs—a philosophy of higher ed that remains popular with conservatives, demonstrated at the federal level by President Donald Trump’s ambition to promote vocational and trade schools.

Walker ultimately failed to alter the university system’s mission, but succeeded in another effort: weakening tenure. In 2015, via a $73 billion budget, Walker, a Republican, made good on his proposal to eliminate language in the state code that protected tenure and shared governance. His new policy handed the power to set tenure policies to the University of Wisconsin system Board of Regents, of which 16 of 18 members are appointed by the governor. The new rules also gave the regents the ability to fire tenured professors when programs were cut or modified—an option that was previously available only in cases of financial exigency.

Walker’s attack on tenure wasn’t the first, but it “made it big on my radar,” Das Acevedo said. Other tenure experts agreed—Walker’s straightforward attack set in motion a landslide of other conservative efforts to curb tenure.

“A number of the efforts [to erode tenure] have come from Republicans, and they’re often tied to larger complaints about the politics of the academy—that faculty members are too progressive; that they are promoting diversity, equity and inclusion; and that they’re trying to indoctrinate students,” said Tim Cain, associate director and professor of higher education at the University of Georgia’s Louisa McBee Institute of Higher Education.

Between 2012 and 2022, state legislatures considered 13 tenure bans and 3,000 bills that addressed faculty or tenure in some way, according to a 2025 study by University of North Texas professor of higher education Barrett Taylor and Ph.D. student Kimberly Watts. The outright tenure bans proved largely unpopular—to date, no state has fully eliminated tenure for faculty—but many evolved into laws that sought to weaken tenure’s protections without getting rid of the status entirely.

In 2022, Florida enacted a law that green-lighted post-tenure review at public institutions. In 2023, while conservatives fumed over critical race theory, Texas enacted Senate Bill 18, which broadened the grounds for terminating a tenured professor to include “exhibit[ing] professional incompetence” and engaging in ill-defined “conduct involving moral turpitude,” among other reasons.

“What we’re seeing is an increase in these efforts, certainly,” Cain said. “The legislation that was proposed in Texas initially was to ban tenure. What was actually passed and signed into law was weakening tenure. A lot of times legislation changes through the process, and you might see more extreme versions that get watered down in one way or another. But they can still be quite problematic for advocates of faculty and advocates of tenure.”

Tenure advocates aren’t against regular evaluations for tenured professors, but the American Association of University Professors argues that post-tenure review “shouldn’t be undertaken for the purpose of dismissal.” State legislatures have weaponized post-tenure review policies in recent years, giving administrators regular opportunities to review and subsequently sanction or fire tenured faculty without real cause. Ohio’s Senate Bill 1 and Kentucky’s House Bill 4, which both took effect in 2025, implemented post-tenure review for public university faculty. In December, the South Dakota Board of Regents also adopted a post-tenure review policy. The University of Tennessee requires tenured professors to be reviewed every six years. Dan Collier, assistant professor of higher and adult education at the University of Memphis, said the lack of protection for tenured professors in the state is discouraging his pursuit of tenure. On LinkedIn, he announced that he told his dean he didn’t care about tenure—only the related pay bump.

“My protections in Tennessee are nowhere near the same as somebody who would also be protected by a union and other laws that exist in somewhere like Michigan or California,” Collier told Inside Higher Ed.

He hesitated to put all the blame on conservatives, however.

“While certain Republican-led states may be reducing tenure protections more than they have in the past, that’s not to say that Democrats or blue states are actually ramping them up to protect anybody, either,” said Collier.

Exploiting Financial Turmoil

Most tenure policies at both the state and institutional level have always allowed for institutions to lay off tenured faculty in cases of financial exigency—periods of extreme financial distress, similar to personal bankruptcy. Financial exigency serves as a kind of escape hatch that allows institutions to bypass their own policies and make large cuts, including laying off tenured faculty, closing programs or undertaking significant administrative overhaul.

In its 1940 statement on academic freedom, the AAUP said that financial exigency was the only case beyond adequate cause in which tenured faculty can be terminated. The AAUP defines financial exigency as “a severe financial crisis that fundamentally compromises the academic integrity of the institution as a whole and that cannot be alleviated by less drastic means.”

The COVID-19 pandemic and the financial stress it put on college campuses brought about a flurry of financial exigency announcements—at least, on their face, Das Acevedo said. “I realized that a lot of those schools were not actually declaring financial exigency,” she said. “They were saying ‘financial exigency,’ and citing difficulties and the pandemic and whatnot, but they weren’t declaring themselves to be in a state of financial exigency.”

Still, the pandemic normalized tenured faculty layoffs in periods of financial strain.

“Many small liberal arts colleges had used the pandemic, in many cases, as an excuse to reorganize the layout of faculty,” said Anita Levy, senior program officer at the AAUP. “So yes, there probably was an acceleration at that moment” of tenured faculty layoffs.

It’s not exactly that anything about tenure has changed. It’s more that universities, like many other employers, have become more willing to skirt the boundaries of what is legally permissible.”

—Deepa Das Acevedo, legal anthropologist and tenure researcher at Emory University

William Paterson University in New Jersey laid off 13 tenured or tenure-track professors mid-pandemic in 2021 and proposed cutting an additional 150 professors over the course of three years, even though the institution never formally declared financial exigency. Also in 2021, the Kansas Board of Regents voted to allow its universities to terminate employees, including tenured professors, without declaring financial exigency. In 2024, the University of Wisconsin Board of Regents voted to lay off 35 tenured faculty members in University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s now-shuttered College of General Studies—a decision that Walker’s 2015 efforts allowed for.

Despite the hair-trigger firings after Kirk’s death, reductions in force remain the biggest threat to tenured professors at present, said Das Acevedo. “The overwhelming majority of tenured faculty lose their jobs not because they were fired for a cause, but because they were the victim of a [reduction in force],” she said.

She underscored the point with a statistic: More tenured faculty members have lost their jobs as the result of a RIF at 13 universities over the past five years than the total number of faculty members who were fired for cause at all universities in the last 20 years.

When tenured professors lose their jobs, colleges and universities are increasingly replacing those roles with adjunct appointments, which give institutions more flexibility in their staffing—and, therefore, spending—year to year. The trend threatens tenure and academic freedom in a different way: by limiting the number of professors who are granted tenure’s traditional protections, said Levy.

“There has been an increase in contingent faculty appointments, which influences how the rights of others are treated on campus,” Levy said. “In other words, right now, 21 percent of the academic labor force is tenured. While the AAUP holds that all full-time faculty members, regardless of rank, should be considered eligible for the protections of tenure, that’s not the case, unfortunately, in much of higher ed.” A 2023 study from the AAUP showed that, in the fall of that year, 23 percent of faculty held full-time tenured positions, down from 39 percent in fall 1987. Between fall 2002 and fall 2023, the number of contingent appointments increased by 65 percent, while tenured appointments increased by only 6 percent and tenure-track appointments fell by 7 percent.

The shift in favor of hiring adjunct faculty reflects a change in leadership strategy, said Collier. “You have HR policies that continuously change to favor administrators, and intentions to corporatize higher education and treat faculty more as employees instead of shared governance,” he said.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | blankvoid, chiravan39, Lee Lawson and PeskyMonkey/iStock/Getty Images

Protest as Fireable Offense

Tenure isn’t dead quite yet—several faculty members fired or put on leave after Kirk’s death have been reinstated in recent months. The University of South Dakota tried to fire art professor Michael Hook over his post about Kirk before abandoning the effort in October amid a legal battle. Darren Michael, a tenured professor of theater at Austin Peay State University, was reinstated in December and paid $500,000 to reimburse him for counseling services, though part of the settlement dictates that Michael will resign in May. At Florida Atlantic University, Karen Leader and finance professor Rebel Cole, both tenured, returned to the classroom in November following two months of paid administrative leave.

Their untenured colleague Kate Polak wasn’t so lucky. Polak, an English instructor, was put on leave in September after the university received complaints that she “celebrated” Kirk’s murder online, including writing that seeing him killed was a “win.” The university announced last week that she would not return to her position.

Institutions haven’t been consistent in how they apply social media speech standards. For example, the University of Tennessee at Knoxville suspended anthropology professor Tamar Shirinian for posting on social media that Kirk was a “disgusting psychopath” and that his wife was a “sick fuck for marrying him.” Nine years earlier, when protesters stopped traffic in Charlotte, N.C., after police shot and killed a Black man in an apartment parking lot, UT Knoxville law professor Glenn Reynolds suggested on Twitter that motorists “run them [the protesters] down.” University officials criticized Reynolds’s tweet, but did not sanction him and ultimately said it was an “exercise of his First Amendment rights.”

You get celebrated for all things social justice, but once you try to advocate for justice in Palestine, you’re basically killing your career and no one will stand by you.”

—Sang Hea Kil, former tenured justice studies professor at San José State University

Speech-related sanctions became more common a few years ago, as the American political landscape slid to the right and online cancel culture made it easy to wield a pressure campaign against universities. Student and faculty protests and counterprotests over Israel’s actions in Gaza following Hamas’s Oct. 7 terrorist attack attracted a variety of university responses, but faculty sanctions or firings were more sporadic than they are now, Das Acevedo said. Among those punished was Maura Finkelstein, who is Jewish and a tenured associate professor at Muhlenberg College. She reposted a statement from a Palestinian American artist that criticized Zionists and told readers not to “welcome them in your spaces” or “make them feel comfortable.”

Most recently, San José State University fired Sang Hea Kil, a tenured professor in the justice studies department who had worked at the university since 2007. University officials took issue with her advocacy for Palestine—but it was her activist work that got her hired in the first place, she said.

“My department hired me as a scholar activist,” she said. “I won a lot of awards as a student activist … and so I did not miss a beat when I arrived at my tenure-track position, and I kept on doing scholar-activist things.”

Kil’s work has always gotten under administrators’ skin; even before she was tenured, she helped lead a successful campaign against internal corruption that led to the resignations of several upper-level administrators. But things changed in 2024.

“The two things that I think that are different 1769462754 are one, new McCarthyism heralded by the Trump administration, and then two, Palestinian exceptionalism,” she said. “You get celebrated for all things social justice, but once you try to advocate for justice in Palestine, you’re basically killing your career and no one will stand by you.”

Kil and Collier agree that the shifting political landscape is partially to blame for the changing rules. If faculty members tick off conservative politicians, it can lead to serious financial and political consequences for the entire institution, Collier said.

“Upper administrators are going to be very, very risk-averse right now, because who wants to get the attention of the Trump administration at the moment?” said Collier. “If they’re focused on Harvard and they’re focused on Columbia, and you are at a regional institution [that] hasn’t gotten selected attention, are you going to push that envelope and get that attention? Because what they’re doing to those larger institutions would be extremely harsh penalties for a less-resourced institution.”

Kil and others believe that she is the first full professor fired from an American college or university for pro-Palestine speech.

“My case becomes really important because they’re going after the tenure system,” she said. The progression from Salaita’s revoked tenure offer in 2014, to Finkelstein in 2024 and Kil in 2025, “shows the escalation that higher ed administrators are willing to go in this political context.”

The weakening of tenure isn’t due to a flaw in the tenure system, Das Acevedo stressed, but to institutions’ increasing refusal to stand up for the traditional protections.

“It’s not exactly that anything about tenure changed,” Das Acevedo said. “It’s more that universities, like many other employers, have become more willing to skirt the boundaries of what is legally permissible, or outright go beyond what is legally permissible, and either pay the consequences in the form of a financial settlement or, in some cases, just not suffer any consequences.”

(This story has been updated to correct Dan Collier’s title. He’s an assistant professor of higher and adult education at the University of Memphis.)