While Gen Z is showing less interest in the normalised alcohol and drug excess that dogged their preceding generations, England and Wales’ most recent stats confirmed that 16.5 per cent of people aged between 16 to 24-years-old took an illegal drug in the last year.

Additionally, a 2024 report by Universities UK found that 18 per cent of students have used a drug in the past with 12 per cent imbibing across the previous 12 months. With a UK student population of 2.9m, this suggests the drug-savvy portion is around 348,000 to 522,000 people.

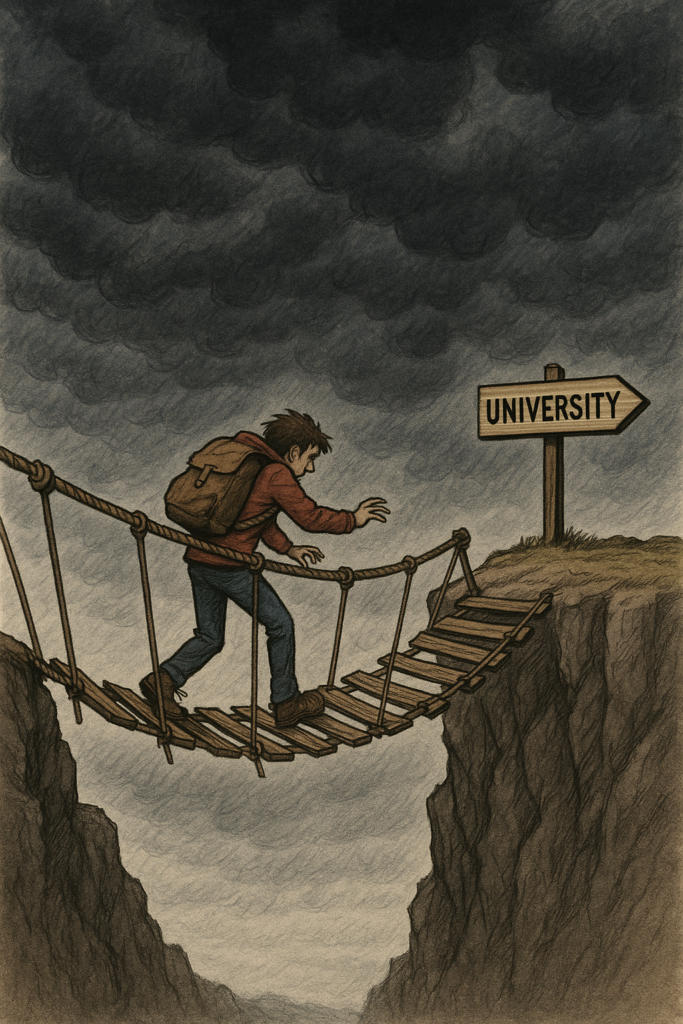

It’s prudent, therefore, for anyone involved within student safety provision to know that the UK is currently mired in a drug death crisis – a record 5,448 fatalities were recorded in England and Wales in the most recent statistics, while Scotland had 1,172, the highest rate of drug deaths in Europe.

In an attempt to ameliorate some of this risk, seven UK universities recently took delivery of nitazene strips to distribute among students, facilitated by the charity Students Organising for Sustainability (SOS-UK). These instant testing kits – not dissimilar to a Covid-19 lateral flow test in appearance – examine pills or powders for nitazenes: a class of often deadly synthetic opioids linked with 458 UK deaths between July 2023 and December 2024.

While these fatalities will have most likely been amongst older, habitual users of heroin or fake prescription medicines, these strips form part of a suite of innovative solutions aimed at helping students stay safe(r) if they do choose to use drugs.

The 2024 Universities UK report suggested drug checking and education as an option in reducing drug-related harm, and recommended a harm reduction approach, adding: “A harm reduction approach does not involve condoning or seeking to normalise the use of drugs. Instead, it aims to minimise the harms which may occur if students take drugs.”

With that in mind, let’s consider a world where harm reduction – instead of zero tolerance – is the de facto policy and how drug checking or drug testing plays a part in that.

Drug checking and drug testing

Drug checking and drug testing are terms that often get used interchangeably but have different meanings. Someone using a drug checking service can get expert lab-level substance analysis, for contents and potency, then a confidential consultation on these results during which they receive harm reduction advice. In the UK, this service is offered by The Loop, a non-profit NGO that piloted drug checking at festivals in 2016 and now have a monthly city centre service in Bristol.

Drug testing can take different forms. First, there is the analysis of a biological sample to detect whether a person has taken drugs, typically done in a workplace or medical setting. There are also UK-based laboratories offering substance analysis, that then gets relaid to the public in different ways.

WEDINOS is an anonymous service, run by Public Health Wales since 2013, where users send a small sample of their substance alongside a downloadable form. After testing, WEDINOS posts the results on their website (in regards to content but not potency) normally within a few weeks.

MANDRAKE is a laboratory operating out of Manchester Metropolitan University. It works in conjunction with key local stakeholders to test found or seized substances in the area. It is often first with news regarding adulterated batches of drugs or dangerously high-strength substances on the market.

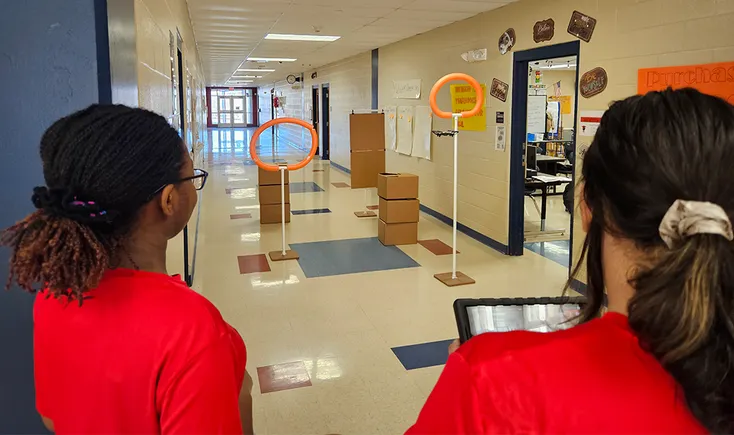

Domestic testing is also possible with reagents tests. These are legally acquired chemical compounds that change colour when exposed to specific drugs and can be used at home. They can provide valuable information as to the composition of a pill or powder but do not provide information on potency. The seven UK universities that took delivery of nitazene strips were already offering reagents kits to students as part of their harm reduction rationale.

Although the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 specifies that certain activities must not be allowed to take place within a university setting, the Universities UK report argued that universities have some discretion on how to manage this requirement. Specifically, it stated: “The law does not require universities to adopt a zero tolerance approach to student drug use.”

How to dispense testing apparatus

The mechanisms differ slightly between SUs but have broad similarities. We spoke with Newcastle and Leeds (NUSU and LUU) who both offer Reagent Tests UK reagent testing kits, fentanyl strips and now nitazene strips. Reagent’s UK kits do not test for either of these two synthetic opioids. They vary in strength compared to heroin – and there are multiple analogues of nitazene that vary in potency – but an established ballpark figure is at least 50 times as strong.

All kits and tests are free. Newcastle’s are available from the Welfare and Support centre, in an area where students would have to take part in an informal chat with a member of staff to procure a kit. “We won’t ask for personal details. However, we do monitor this and will check in with a welfare chat if we think this would be helpful,” says Kay Hattam, Wellbeing and Safeguarding Specialist at NUSU. At Leeds, they’re available from the Advice Office and no meeting is required to collect a kit.

Harm reduction material is offered alongside the kits. “We have developed messaging to accompany kits which is clear on the limitations of drug testing, and that testing does not make drugs safe to use,” says Leeds University Union.

Before the donation, kits were both paid for by the respective unions and neither formally collected data on the results. Both SUs both make clear that offering these kits is not an encouragement of drug use. Kay Hattam draws an analogy: “If someone was eating fast food every day and I mentioned ways to reduce the risks associated with this, would they feel encouraged to eat more? I would think not. But it might make them think more about the risks.”

You’ll only encourage them

In 2022, in a report for HEPI, Arda Ozcubukcu and Graham Towl argued, “Drug use matters may be much more helpfully integrated into mental health and wellbeing strategies, rather than being viewed as a predominantly criminal justice issue.”

The evidence backs up the view that a harm reduction approach does not encourage drug use. A 2021 report authored by The Loop’s co-founder Fiona Measham, Professor in Criminology at the University of Liverpool, found that over half of The Loop’s users disposed of a substance that tested differently to their intended purchase, reducing the risk of poisoning. Additionally, three months after checking their drugs at a festival, around 30 per cent of users reported being more careful about polydrug use (mixing substances). One in five users were taking smaller doses of drugs overall. Not only does this demonstrate that better knowledge reduces risk of poisoning in the short-term, but it also has enduring positive impacts on drug-using behaviours.

SOS-UK has developed the Drug and Alcohol Impact scheme with 16 universities and students’ unions participating. This programme supports institutions in implementing the Universities UK guidance by using a variety of approaches to educate and support students in a non-stigmatising manner.

Alongside them is SafeCourse, a charity founded by Hilton Mervis after his son Daniel, an Oxford University student, died from an overdose in 2019. The charity – which counts the High Court judge Sir Robin Knowles and John de Pury, who led the development of the 2024 sector harm reduction framework, among its trustees – is working to encourage universities to move away from zero tolerance.This is through various means, including commissioning legal advice to provide greater clarity on universities’ liability if they are not adopting best practice, and checking in one year on from the Universities UK report, to ascertain how they’re adapting to the new era of harm reduction.

SafeCourse takes the view that universities must not allow themselves to be caught up prosecuting a failed war on drugs when their focus should be student safety, wellbeing and success. A harm reduction approach is the best way of achieving those ends.