by Yusuf Oldac and Francisco Olivas

We recently embarked upon a project to explore the development of higher education research topics over the last decades. The results were published in Review of Education. Our aim was to thematically map the field of research on higher education and to analyse how the field has evolved over time between 2000 and 2021. This blog post summarises our findings and reflects on the implications for HE research.

HE research continues to grow. HE researchers are located in globally diverse geographical locations and publish on diversifying topics. Studies focusing on the development of HE with a global-level analysis are increasingly emerging. However, most of these studies are limited to scientometric network analyses that do not include a content-related focus. In addition, they are deductive, indicating that they tried to fit their new findings into existing categories. Recently, Daenekindt and Huisman (2020) were able to capture the scholarly literature on higher education through an analysis of latent themes by utilising topic modelling. This approach got attention in the literature, and the study’s contribution was highlighted in an earlier SRHE blog post. We also found their study useful and built on it in our novel analysis. However, their analysis focused only on generating topics from a wide range of higher education journals and did not identify explanatory factors, such as change over the years or the location of publication. After identifying this gap, we worked towards moving one step further.

A central contribution of our study is the inclusion of a set of research content explanatory factors, namely: time, region, funding, collaboration type, and journals, to investigate the topics of HE research. In methodological terms, our study moves ahead of the description of the topic prevalence to the explanation of the prevalence utilizing structural topic modelling (Roberts et al, 2013).

Structural topic modelling is a machine learning technique that examines the content of provided text to learn patterns in word usage without human supervision in a replicable and transparent way (Mohr & Bogdanov, 2013). This powerful technique expands the methodological repertoire of higher education research. On one hand, computational methods make it possible to extract meaning from large datasets; on the other, they allow the prediction of emerging topics by integrating the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Nevertheless, many scholars in HE remain reluctant to engage with such methods, reflecting a degree of methodological conservatism or tunnel vision (see Huisman and Daenekindt’s SRHE blog post).

In this blog post, our intention is not to go deep into the minute details of this methodological technique, but to share a glimpse of our main findings through the use of such a technique. With the corpus of all papers published between 2000 and 2021 in the top six generalist journals of higher education, as listed by Cantwell et al (2022) and Kwiek (2021) both, we analysed a dataset of 6,562 papers. As a result, we identified 15 emergent research topics and several major patterns that highlight the thematic changes over the last decades. Below, we share some of our findings, accompanied by relevant visualisations.

Glimpse at the main findings with relevant visuals

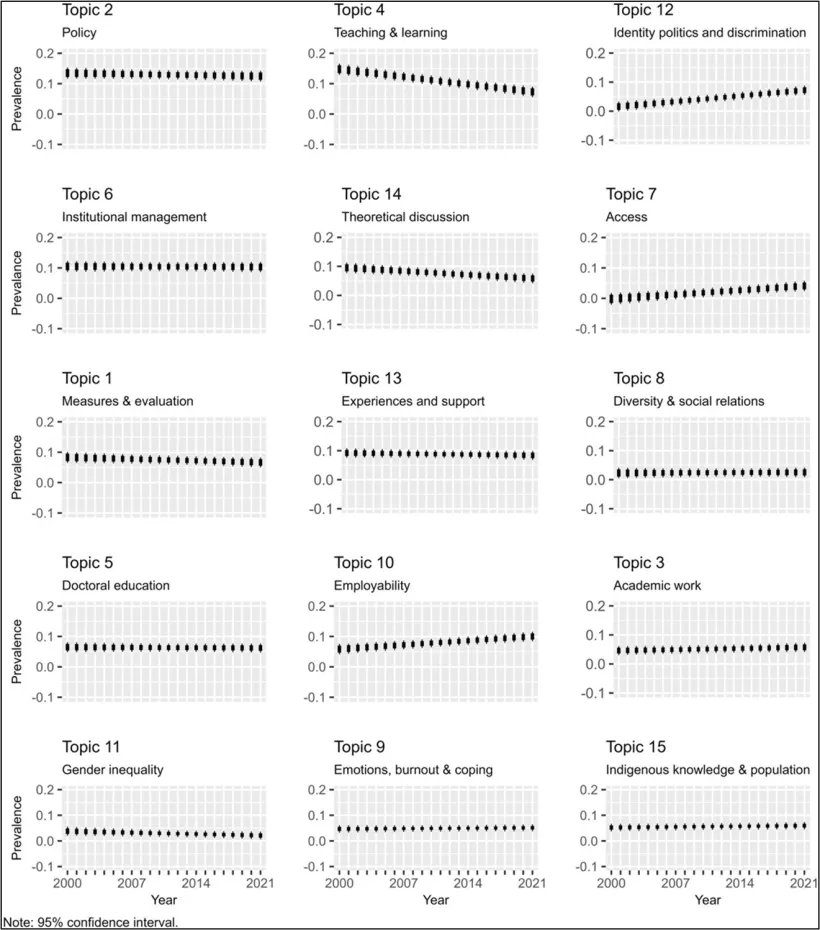

The emergent 15 higher education topics and three visibly rising ones

Our topic modelling analysis revealed 15 distinct topics, which are largely in line with the topics discussed in previous studies on this line (eg Teichler, 1996; Tight, 2003; Horta & Jung, 2014). However, there are added nuances in our analysis. For example, the most prevalent topics are policy and teaching/learning, which are widely acknowledged in the field, but new themes have emerged and strengthened over time. These themes include identity politics and discrimination, access, and employability. These areas, conceptually linked to social justice, have become central to higher education research, especially in US-based journals but not limited to them. The visual below demonstrates the changes over the years for all 15 topics.

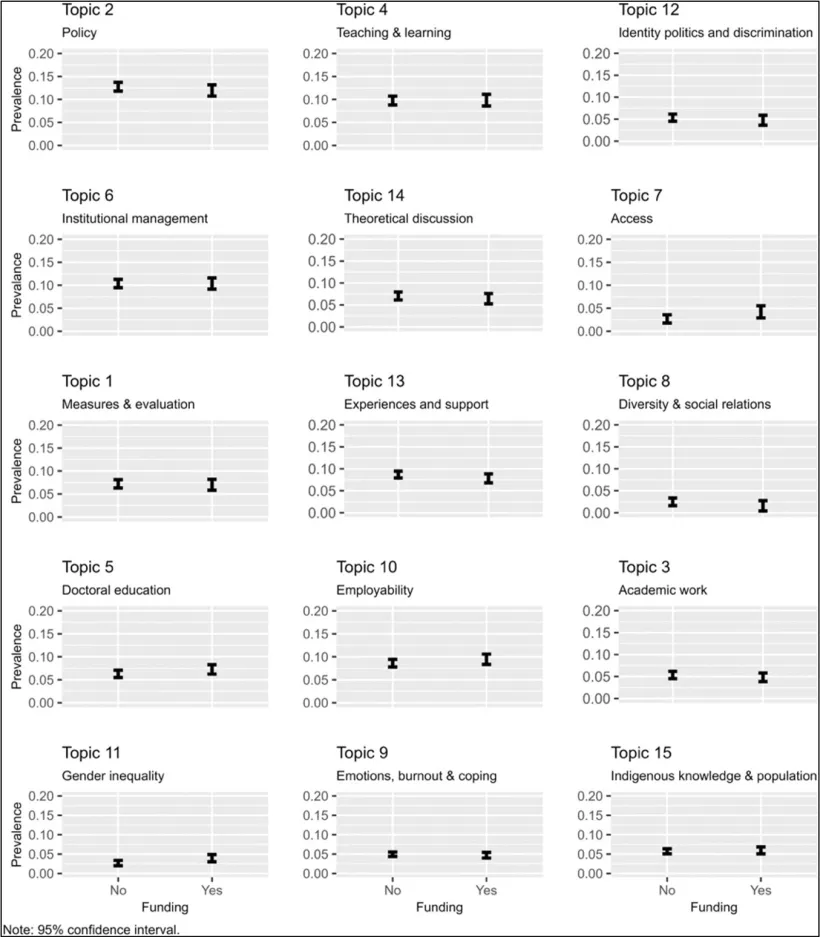

- The Influence of funding on higher education research topics

Research funding plays a crucial role in shaping certain topics, particularly gender inequality, access, and doctoral education. Studies that received funding exhibited a higher prevalence of these socially significant topics, underscoring the importance of targeted funding to support research with social impact. The data visualisation below summarises the influence of reported funding for each topic. The novelty of this pattern needs to be highlighted because we have not come across a previous study looking into the influence of funding existence on research topics in the higher education field.

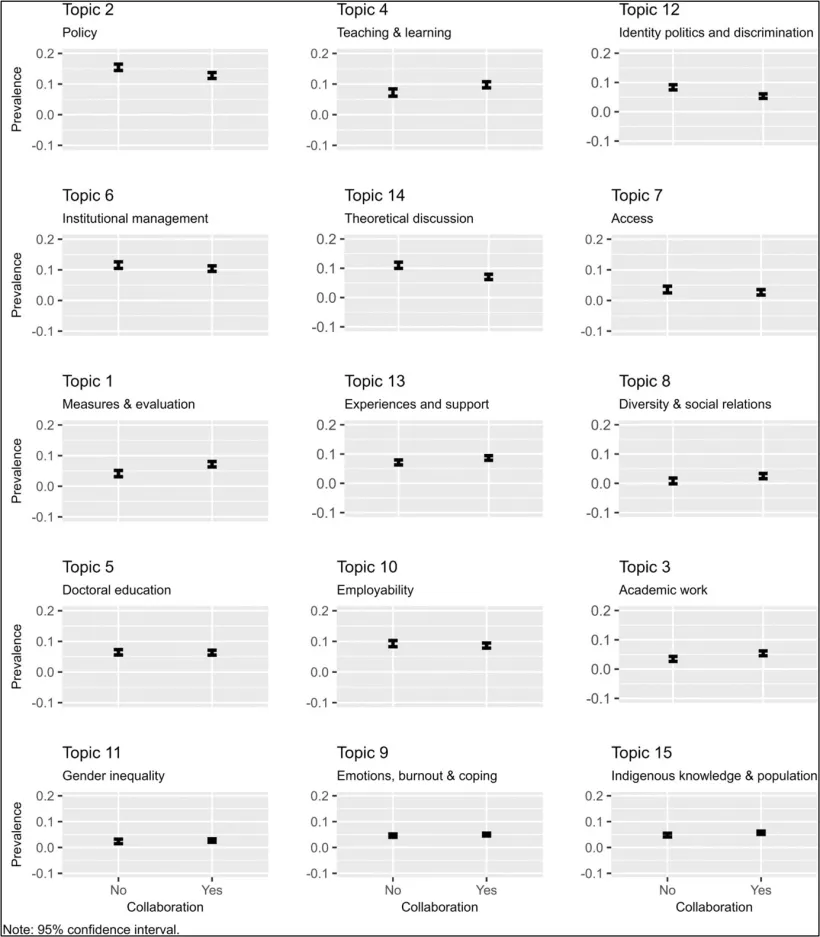

- The impact of collaboration on higher education research topics

Collaborative publications are more prevalent in topics such as teaching and learning, and diversity and social relations. By contrast, theoretical discussions, identity politics, policy, employability, and institutional management are more common in solo-authored papers. This pattern aligns with the nature of these topics and the data requirements for research. Please see the visualised data below.

We highlight that although the relationship between collaboration and citation impact or researcher productivity is well studied, we are not aware of any evidence of the effect of collaboration patterns on topic prevalence, particularly in studies focusing on higher education. So, this finding is a novel contribution to higher education research.

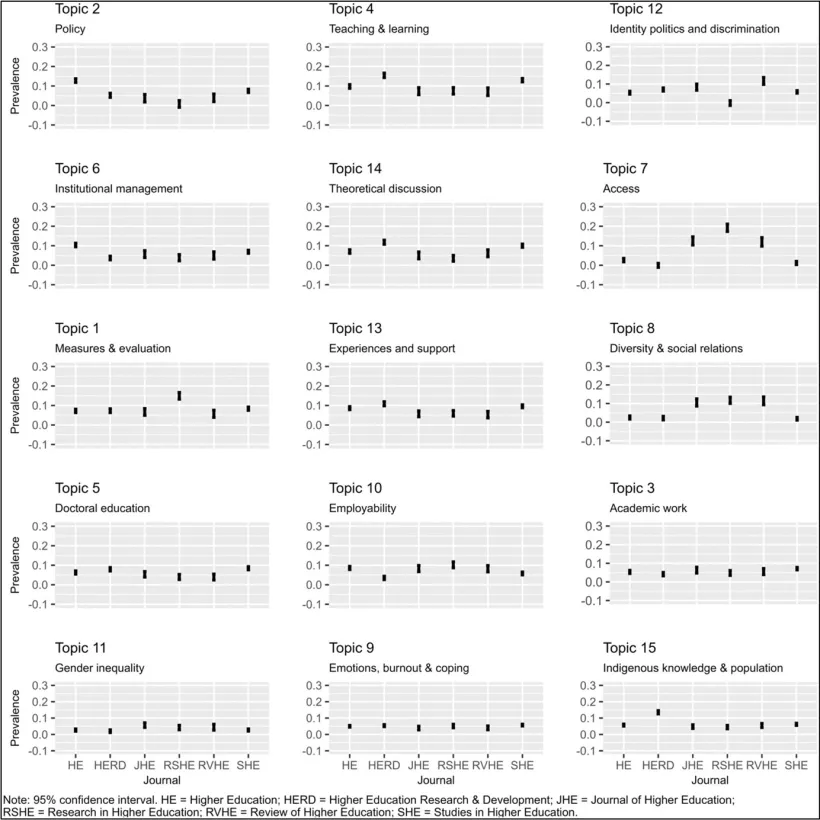

- Higher education journals’ topic preferences

Although the six leading journals claim to be generalist, our analysis shows they have differing publication preferences. For example, Higher Education focuses on policy and university governance, while Higher Education Research and Development stands out for teaching/learning and indigenous knowledge. Journal of Higher Education and Review of Higher Education, two US-based journals, have the highest prevalence of identity politics and discrimination topics. Last, Studies in Higher Education has a significantly higher prevalence in teaching and learning, theoretical discussions, doctoral education, and emotions, burnout and coping than most of the journals.

- Regional differences in higher education research topics

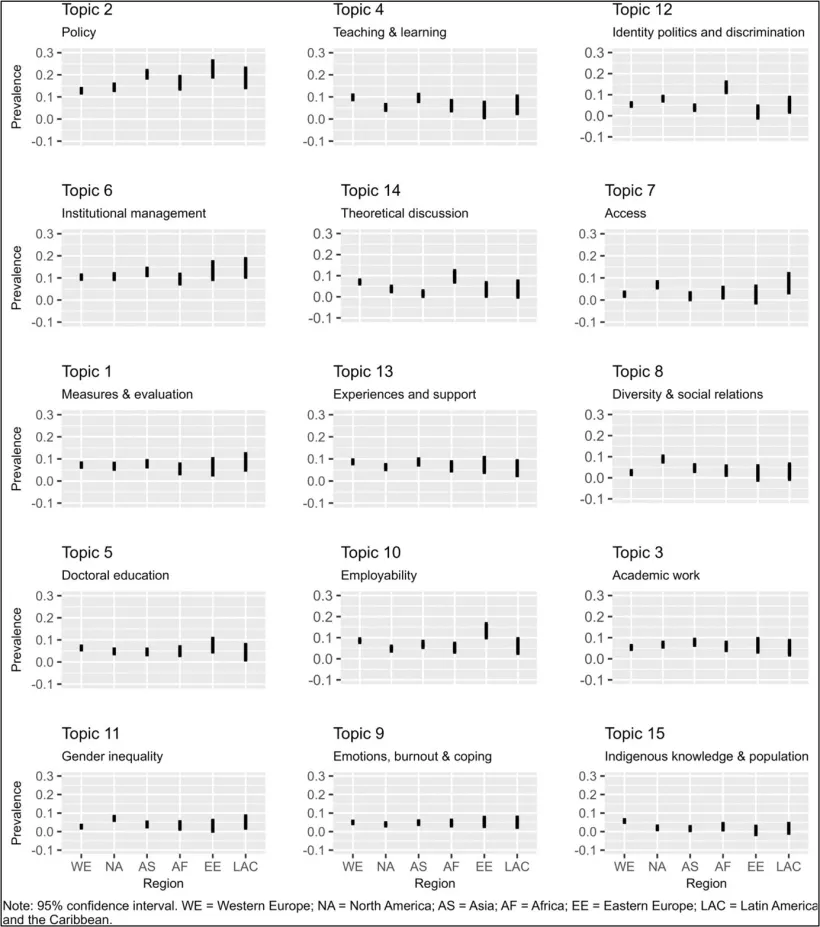

Topic focus varies significantly by the region of the first author. First, studies from Asia exhibit the highest prevalence of academic work and institutional management. Studies from Africa show a higher prevalence of identity politics and discrimination. Moreover, studies published by first authors from Eastern European countries stand out with the higher prevalence of employability. Lastly, the policy topic has a high prevalence across all regions. However, studies with first authors from Asia, Eastern Europe, Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean showed a higher prevalence of policy research in higher education than those from North America and Western Europe. By contrast, indigenous knowledge is most prominent in Western Europe (including Australia and New Zealand). The figure below demonstrates these in visual format.

Concluding remarks

Higher education research has grown and diversified dramatically over the past two decades. The field is now established globally, with an ever-expanding array of topics and contributors. In this blog post, we shared the results of our analysis in relation to the influence of targeted funding, collaborative practices, regional differences, and journal preferences on higher education research topics. We have also indicated that certain topics have risen in prevalence in the last two decades. More patterns are included in the main research study published in Review of Education.

It is important to note that we could only include the higher education papers published up to 2021, the latest available data year when we started the analyses. The impact of generative artificial intelligence and recent major shifts in the global geopolitics, including the new DEI policies in the US and overall securitisation of science tendencies, may not be reflected fully in this dataset. These themes are very recent, and future studies, including replications with similar approaches, may help provide newly emerging patterns.

Dr Yusuf Oldac is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Education Policy and Leadership at The Education University of Hong Kong. He holds a PhD degree from the University of Oxford, where he received a full scholarship. Dr Oldac’s research spans international and comparative higher education, with a current focus on global science and knowledge production in university settings.

Dr Francisco Olivas obtained his PhD in Sociology from The Chinese University of Hong Kong. He joined Lingnan University in August 2021. His research lies in the intersections between cultural sociology, social stratification, and subjective well-being, using quantitative and computational methods.