Upward transfer is viewed as a mechanism to provide college students with an accessible and affordable on-ramp to higher education through two-year colleges, but breakdowns in the credit-transfer process can hinder a student’s progress toward their degree.

A recent survey by Sova and the Beyond Transfer Policy Advisory Board found the average college student loses credits transferring between institutions and has to repeat courses they’ve already completed. Some students stop out of higher education altogether because transfer is too challenging.

CourseWise is a new tool that seeks to mitigate some of these challenges by deploying AI to identify and predict transfer equivalencies using existing articulation agreements between institutions. So far, the tool, part of the AI Transfer and Articulation Infrastructure Network, has been adopted at over 120 colleges and universities, helping to provide a centralized database for credit-transfer processes and automate course matching.

In the most recent episode of Voices of Student Success, host Ashley Mowreader speaks with Zachary Pardos, an associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley, about how CourseWise works, the human elements of credit transfer and the need for reliable data in transfer.

An edited version of the podcast appears below.

Q: As someone who’s been in the education-technology space for some time, can you talk about this boom of ed-tech applications for AI? It seems like it popped up overnight, but you and your colleagues are a testament to the fact that it’s been around for decades.

Zach Pardos, associate professor at UC Berkeley and the developer of CourseWise

A: As soon as a chat interface to AI became popularized, feasible, plausible and useful, it opened up the space to a lot of people, including those who don’t necessarily have a computer science background. So in a way, it’s great. You get a lot more accessibility to this kind of application and work. But there have also been precepts—things that the field has learned, things that people have learned who’ve been working in this space for a while—and you don’t want to have to repeat all those same errors. And in many ways, even though the current generation of AI is different in character, a lot of those same precepts and missteps still apply here.

Q: What is your tool CourseWise and why is it necessary in the ed-tech space?

A: CourseWise is a spinoff of our higher education and AI work from UC Berkeley. It is meant to be a credit-mobility accelerator for students and institutions. It’s needed because the greatest credit-mobility machine in America, the thing that gets families up in socioeconomic status, is education. And it’s the two-year–to–four-year transition often that does that, where you can start at a more affordable school that gives two-year associate’s degrees and then transition to a four-year school.

But that pathway often breaks down. It’s often too expensive to maintain, and so for there to be as many pathways as possible that are legitimate between institutions, between learning experiences, basically acknowledging what a student has learned and not making them do it again, requires us to embrace technology.

Q: Can you talk more about the challenges with transfer and where course equivalency and transfer pipelines can break down in the transition between the two- and four-year institutions?

A: Oftentimes, when a student applies to transfer, they’ll have their transcript evaluated [by the receiving institution], and it’ll be evaluated against existing rules.

Sometimes, when it’s between institutions that have made an effort to establish robust agreements, the student will get most of their credit accepted. But in instances where there aren’t such strong ties, there’s going to be a lot of credit that gets missed, and if the rules don’t exist, if the institution does go through the extra effort, or the student requests extra effort to consider credit that hasn’t been considered before, this can be a very lengthy process.

Sometimes that decision doesn’t get made until after the student’s first or second semester, semesters in which they maybe had to decide whether or not to take such a course. So it really is a matter of not enough acknowledgment of existing courses and then that process to acknowledge the equivalency of past learning being a bit too slow to best serve a learner.

Q: Yeah. Attending a two-year college with the hopes of earning a bachelor’s degree is designed to help students save time and money. So it’s frustrating to hear that some of these students are not getting their transfer equivalencies semesters into their progress at the four-year, because that’s time and energy lost.

A: Absolutely. It’s unfortunately, in many cases, a false promise that this is the cheaper way to go, and it ends up, in many cases, being more expensive.

Q: We can talk about the transfer pipeline a lot, but I’ll say one more thing: The free marketplace of higher education and the idea that a student can transfer anywhere is also broken down by a lack of transfer-articulation agreements, where the student’s credits aren’t recognized or they’re only recognized in part. That really hinders the student’s ability to say, “This is where I want to go to college,” because they’re subject to the whims of the institutions and their agreements between each other.

A: That’s right, and it’s not really an intentional [outcome]. However, systems that have a power dynamic often have a tendency not to change, and that resistance to change, kind of implicitly, is a commitment not to serve students correctly.

Accreditors Weigh In

The Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions (C-RAC) supports the exploration and application of AI solutions within learning evaluation and credit transfer, according to a forthcoming statement from the group to be released Oct. 6. Three accrediting commissions, MSCHE, SACSCOC and WSCUC, are holding a public webinar conversation to discuss transfer and learning mobility, with a focus on AI and credit transfer on Oct. 6. Learn more here.

So what you do need is a real type of intervention. Because it’s not in any one spot, you could argue, and you could also make the argument that every institution is so idiosyncratic in its processes that you would have to do a separate study at every institution to figure out, “OK, how do we fix things here?” But what our research is showing on the Berkeley end is that there are regularities. There are patterns in which credit is evaluated, and where you could modify that workflow to both better serve the institution, so it’s not spending so many resources on manually considering equivalencies, and serve the student better by elevating opportunities for credit acceptance in a more efficient way.

That’s basically what CourseWise is. It’s meant to be an intervention that serves the institution and serves the student by recognizing these common patterns to credit acceptance and leveraging AI to alleviate the stress and friction that currently exists in affording that credit.

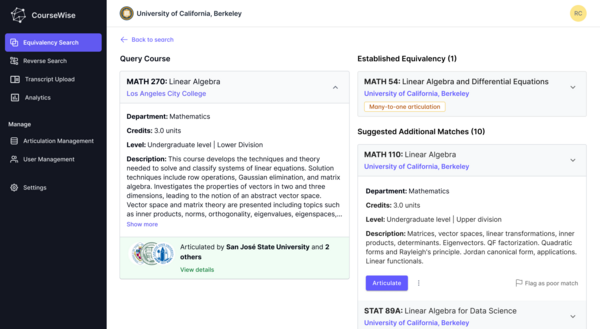

Q: Can you walk us through where CourseWise fits into the workflow? How does it work practically?

A: CourseWise is evolving in its feature set and has a number of exciting features ahead, which maybe we’ll get to later. But right now, the concrete features are that on the administrator side, on the staff or admissions department side, you upload an institution’s existing articulation agreements—so if you’re a four-year school, it’s your agreements to accept credit from two-year schools.

So then, when you receive transcripts from prospective transfer students, the system will evaluate that transcript to tell you which courses match existing rules of yours, where you’ve guaranteed credit, and then it’ll also surface courses that don’t already have an agreement.

If there’s a high-confidence AI match, it’ll bring that to the administrator’s attention and say, “You should consider this, and here’s why.” It’ll also bring to their attention, “Here’s peer institutions of yours that have already accepted that course as course-to-course credit.”

CourseWise compares classes in institutions’ catalogs to identify existing agreements for credit transfer and possible course-to-course transfers to improve student outcomes.

Q: Where are you getting that peer-to-peer information from?

A: We think of CourseWise as a network, and that information on what peer institutions are doing is present. We have a considerable number of institutions from the same system. California is one—we have 13 California institutions, and we’re working on more. The other is State University of New York, SUNY. We have the SUNY system central participating in a pilot. It’ll be up to the individual institutions to adopt the usage. But we have data at the system-center level, and because of that centralized data, we are able to say, for every SUNY institution that’s considering one of the AI credit acceptance requests, give that context of, “Here are other four-year peer institutions within your system that already accept this—not just as generic elective credit, but accept it as perhaps degree satisfying, or at least course-to-course credit.”

Q: That’s awesome; I’m sure it’s a time saver. But where do the faculty or staff members come back into the equation, to review what the AI produced or to make sure that those matches are appropriate?

A: Faculty are a critical part of the governance of credit equivalency in different systems. They have different roles; often it’s assumed that faculty approve individual courses. That’s true in most cases. Sometimes it’s committees; different departments will have a committee of faculty, or they may even have a campus standing committee that considers this curricular committee that makes those decisions.

But what CourseWise is doing right now to incorporate faculty appropriately is we’re allowing for the institution to define what is that approval workflow and the rules around that. If it’s a lower-division statistics class, can your admission staff make that decision on acceptability, even if it’s not existing in a current agreement?

Under what circumstances does it need to be routed to a faculty member to approve? What kind of information should be provided to that faculty member if they don’t have it, making it easy to request information, like requesting a syllabus be uploaded by the sending institution or something to that effect?

Oftentimes, this kind of approval workflow is done through a series of emails, and so we’re trying to internalize that and increase the transparency. You have different cases that get resolved with respect to pairs of courses, and you can see that case. You can justify why a decision was made, and it can be revisited if there’s a rebuttal to that decision.

Now, over time, what we hope the field can see as a potential is perhaps for certain students, let’s say, coming from out of state; it’s more a faculty committee who gives feedback to a kind of acceptance algorithm that is then able to make a call, and they can veto that call. But it creates a default; like with ChatGPT, there’s an alignment committee that helps give feedback to ChatGPT answers so that it is better in line with what most users find to be a high-quality response. Because there’s no way that we can proactively, manually accept or evaluate every pair of institutions to one another in the United States—there’s just no FTE count that would allow for that, which means that prospective students from out of state can’t get any guarantee if we keep it with that approach.

Faculty absolutely have control. We’re setting up the whole workflow so an institution can define that. But one of the options we want to give institutions is the option to say, “Well, if the student is coming from out of state or coming from this or that system, you can default to a kind of faculty-curated AI policy.”

Q: That’s cool. I’ve heard from some colleges that they have full teams of staff who just review transcripts every single day. Having a centralized database where you can see past experiences of which courses have been accepted or rejected—that can save so much time and energy. And that’s not even half of what CourseWise is doing.

A: Absolutely, and we work closely with leadership and these institutions to get feedback. And one of the people involved in that early feedback is Isaiah Vance at the Texas A&M University system, and he’s given us similar feedback where, if you have a new registrar or a new leadership that comes in, and they want to know how good the data is, they want that kind of transparency of how were decisions made, if you have that transparency in that organization to look that over, it can really help an institution get comfortable with those past decisions or decide how they should change in the future.

Q: What are some of the outcomes you’ve seen or the feedback you’ve heard from institutions that are using the tool?

A: We have a study that we’re about to embark upon to measure a before-and-after change in how institutions are doing business and how much it’s saving time or not, versus a control of not having the system when making these decisions.

We don’t have the results of that yet. We do have a paper out on where articulation officers, for example, are spending their time. They’re spending a lot of time on looking for the right course that might articulate. So we definitely have identified there is a problem. It’s an open question to what degree CourseWise is remedying that. We certainly are working nonstop to remedy it, but we’re going to measure that rigorously over the next year.

Some early feedback is positive, but also interesting that institutions, many of them, are spending a lot of time getting that initial data uploaded, catalog descriptions, articulations and the rigorousness and validity of that data. Maybe it’s spread across a number of Excel spreadsheets at some institutions—that problem is real—and so I think it’s going to take a field-level or industry-level effort to make sure that everyone can be on board with that data-wrangling stage.

Q: That was my hypothesis, that the tool has a lot of benefits once everything’s all set up and they’ve done the labor of love to hunt down and upload all these documents, find out which offices they’re hiding behind.

A: There are a number of private foundations, funders who are invested in that particular area. So I’m optimistic that there’s a solution out there and that we’ll be a part of that.

Q: I wonder if we can talk about how this tool can improve the student experience with transfer and what it means to have these efficiencies and database to lean back on.

A: Right now, most of the activity is with the four-year schools, because they’re the ones uploading the articulations. They’re the ones evaluating transcripts. But in the next four months, we’re releasing a student-facing planner, which will directly affect students at the sending institutions.

This planner will allow a student who’s at a community college to choose what destination school and major they’re interested in that’s part of the CourseWise network. Then [CourseWise provides] what courses they need to take, or options of courses to take that will transfer into the degree program that they’re seeking, such that when they transfer, they would only have to do the equivalent of two full years of academic work at that receiving school.

It would also let them know what other majors at other institutions they may want to consider because of how much of the credit that they’ve already taken is accepted into the degree programs there. So the student may be 20 percent of the way in completing their initially intended destination program, but maybe they’re 60 percent of the way to another program that they didn’t realize.

Q: What’s next for CourseWise?

A: So the student part is the navigation, the administrator articulation expansion and policy for expansion is creating the pathways; you need a GPS in order to know what the paths are and how to traverse them as a learner. But also states—I mentioned regularities—there are commonalities in how these processes take place, but there’s also very specific state-level concerns and structures, like common course numbering, credit for prior learning, an emphasis on community colleges accepting professional certificate programs and so forth.

I think the future is both increasing that student-facing value, helping with achievement from the student point of view. But then also leveraging the fundamental AI equivalency engine and research to bring in these other ways of acknowledging credit, whether it’s AP credit or job-training credit or certificates or cross-walking between all these different ways in which higher education chooses to speak about learning, right?

If you have a requirement satisfied in general education in California, how do you bring that to New York, given New York’s general education requirements? Are there crosswalks that can be suggested and established with the aid of AI? And I’m excited about connecting these different sorts of dialects of education using technology.