High school history teacher Antoine Stroman says he wants his students to ask “the hard questions” — about slavery, Jim Crow, the murder of George Floyd and other painful episodes that have shaped the United States.

Now, Stroman worries that President Donald Trump’s push for “patriotic education” could complicate the direct, factual way he teaches such events. Last month, the president announced a plan to present American history that emphasizes “a unifying and uplifting portrayal of the nation’s founding ideals,” and inspires “a love of country.”

Stroman does not believe students at the magnet high school where he teaches in Philadelphia will buy this version, nor do many of the teachers I’ve spoken with. They say they are committed to honest accounts of the shameful events and painful eras that mark our nation’s history.

“As a teacher, you have to have some conversations about teaching slavery. It is hard,” Stroman told me. “Teaching the Holocaust is hard. I can’t not teach something because it is hurtful. My students will come in and ask questions, and you really have to make up your mind to say, ‘I can’t rain dance around this.’”

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

These are tense times for educators: In recent weeks, dozens of teachers and college professors have been fired or placed under investigation for social media posts about their views of slain 31-year-old conservative activist Charlie Kirk, ushering in a slew of lawsuits and legal challenges.

In Indiana, a portal called Eyes on Education encourages parents of school children, students and educators to submit “real examples” of objectionable curricula, policies or programs. And nearly 250 state, federal and local entities have introduced bills and other policies that restrict the content of teaching and trainings related to race and sex in public school. Supporters of these laws say discussion of such topics can leave students feeling inferior or superior based on race, gender or ethnicity; they believe parents, not schools, should teach students about political doctrine.

“It has become very difficult to navigate,” said Jacob Maddaus, who teaches high school and college history in Maine and regularly participates in workshops on civics and the Constitution, including programs funded by the Sandra Day O’Connor Institute. Almost 80 percent of teachers surveyed recently by the institute say they have “self-censored” in class due to fear of pushback or controversy. They also reported feeling underprepared, unsupported and increasingly afraid to teach vital material.

After Kirk’s death Trump launched a new “civics education coalition,” aimed at “renewing patriotism, strengthening civic knowledge, and advancing a shared understanding of America’s founding principles in schools across the nation.” The coalition is made up made up almost entirely of conservative groups, including Kirk’s Turning Point USA, whose chief education officer, Hutz Hertzberg, said in a statement announcing the effort that he “is more resolved than ever to advance God-centered, virtuous education for students.”

So far, no specific guidelines have emerged: Emails to the Department of Education — sent after the government shut down — were not returned.

Related: Teaching social studies in a polarized world

Some students, concerned about the shifting historical narratives, have taken steps to help preserve and expand their peers’ access to civics instruction. Among them is Mariya Tinch, an 18-year-old high school senior from rural North Carolina. “Trump’s goal of teaching ‘patriotic’ education is actually what made me start developing my app, called Revolve Justice, to help young students who didn’t have access to proper civic education get access to policies and form their own political opinions instead of having them decided for them,” she told me.

Growing up in a predominantly white area, Tinch said, “caused civic education to be more polarized in my life than I would like as a young Black girl. A lot of my knowledge in regard to civic education came from outside research after teachers were unable to fully answer my questions about the depth of the issues that we are taught to ignore.”

Other students are upset about federal cuts to history education programs, including National History Day, a 50-year-old nonprofit that runs a history competition for some 500,000 students who engage in original historic research and provides teachers with resources and training. Youth groups are now forming as well, including Voters of Tomorrow, which has a goal of building youth political power by “engaging, educating, and empowering our peers.”

Related: What National Endowment for the Humanities cuts mean for high schoolers like me

There will surely be more attention focused on the founders’ original ideals for America as we approach the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence this July. Some teachers and groups that support civics teachers are creating resources, including the nonprofit iCivics, with its “We can teach hard things — and we should” guidelines.

How all of these different messages resonate with students remains to be seen. In the meantime, Jessica Ellison, executive director of the nonprofit National Council for History Education is fielding a lot of questions from history teachers and giving them specific advice.

“They might be anxious about any teaching that could get them on social media or reported by a student or parent,” Ellison told me, noting the strategy she shares with teachers is to focus on “the three S’s –— sources, state standards and student questions.”

Ellison also encourages teachers to “lean into the work of historians. Read the original sources, the primary sources, the secession documents from Mississippi and put them in front of students. If it is direct from the source you cannot argue with it.”

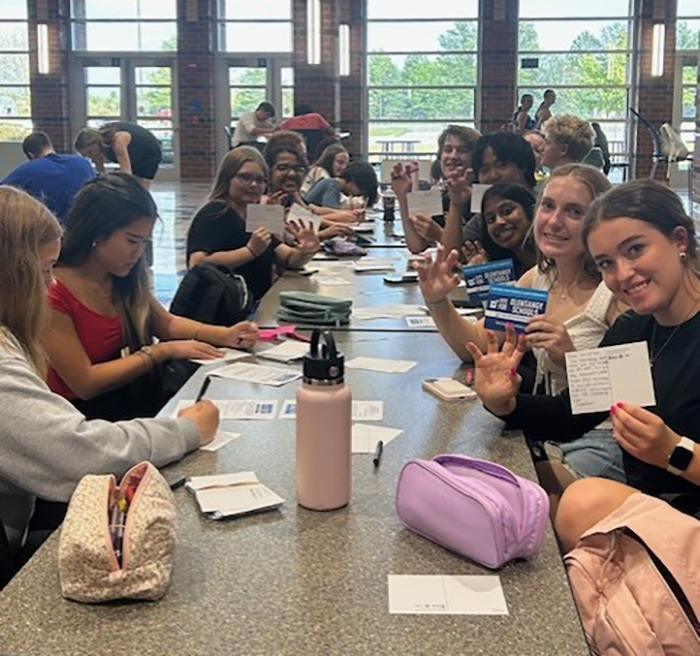

Michael LaFlamme has his own methods: He teaches Advanced Placement government and U.S. history at Olentangy Berlin High School outside of Columbus, Ohio, where many of his students work the polls during elections to see up close how voting works. They learn about civics via a participatory political science project that asks students to write a letter to an elected official. He also encourages students to watch debates or political or Sunday morning news shows with a parent or grandparent, and attend a school board meeting.

“There is so much good learning to be done around current events,” LaFlamme told me, noting that “it becomes more about community and experience. We are looking at all of it as political scientists.”

For Maddaus, the teacher in Maine, there is yet another obstacle: How his students consume news reinforces the enormous obstacles he and other teachers face to keep them informed and thinking critically. Earlier this fall, he heard some of his students talking about a rumor they’d heard over the weekend.

“Mr. Maddaus, is it true? Is President Donald Trump dead?” they asked.

Maddaus immediately wanted to know how they got this false news.

“We saw it on TikTok,” one of the students replied — not a surprising answer, perhaps, given that 4 out of 10 young adults get their news from the platform.

Maddaus says he shook his head, corrected the record and then went back to his regularly scheduled history lesson.

Contact editor in chief Liz Willen at [email protected].

This column about patriotism in education was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.