Fake news is dangerous. But it’s hardly new.

More than 3,000 years ago, the largest chariot battle ever pitted the forces of one of the most powerful pharaohs of ancient Egypt — Ramesses the Great — against the Hittite Empire in Kadesh, near the modern-day border between Lebanon and Syria.

The battle ended in stalemate.

But once back in Egypt, Ramesses spread lies portraying the battle as a major victory for the Egyptians. He had scenes of himself killing his enemies put up on the walls of nearly all his temples.

It was propaganda. “It is all too clear that he was a stupid and culpably inefficient general and that he failed to gain his objectives at Kadesh,” Egyptologist John A. Wilson wrote.

Disinformation in ancient Rome

The Roman general Mark Antony killed himself with his sword after his defeat in the Battle of Actium upon hearing false rumors — fake news — propagated by his lover Cleopatra claiming that she had committed suicide.

American patriots, including the esteemed U.S. statesman and inventor Benjamin Franklin, and their British enemies swapped spurious allegations during the American Revolution that murderous Native Americans were working in league with their adversaries, scalping allies.

How about the 1938 radio drama, “The War of the Worlds”? Adopted from a novel by H.G. Wells, the radio broadcast fooled some listeners into believing that Martians had landed in America. Newspapers of the day said the broadcast sparked panic.

But historians today say the panic was exaggerated. So it was fake news about fake news!

There is no shortage of modern-day instances of fake news. In Myanmar in 2018, the military spearheaded a campaign of fake news, mainly on Facebook, claiming the Rohingya minority had murdered and raped members of the Buddhist majority. The Rohingya were described as dogs, maggots and rapists. The fake news helped trigger violence against the Rohingya that forced 700,000 people to flee their homes.

The irony is that many in Myanmar had turned to Facebook for information because the military had alienated many citizens with its control of the media. But the same military took advantage of the false reports to crack down on the Muslim minority.

Election falsehoods

Similarly, fake news has been used in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka to influence the outcome of elections, hide corruption and stir up religious animosity.

One of the ironies of fake news is it can embolden authoritarian governments to turn the tables and use made-up news as an excuse to crack down on the media. That can enable the regime to control the media message. In other words, fake news to the rescue of autocrats.

But we should not fool ourselves into thinking that fake news can be cured merely through technological solutions, that it’s a product of our times, that it’s mainly political and that it’s peddled only by our opponents. It’s not the property of any one political party or interest.

Fake news takes root in the gray area between truth and fiction, an area we can be quite comfortable in. There is something very enticing about fake news, especially if it aligns with our pre-conceived notions. Yet we are apt to think that fake news is the exception, a new aberration.

We can easily fall victim to fake news in part because we are not always disgusted by lies. We are taught at a very early age that deceit – deception, dishonesty, disinformation – is all around us. And that not all lies are as harmful as others. Our parents read us fairy tales from the earliest of ages, and many tales involve lies.

The telling of fairy tales

Take the ancient fable of “The Cock and the Fox,” included in the medieval collection of Middle Eastern folk tales, “One Thousand and One Nights.”

A hungry fox tries to coax a rooster out of a tree by telling him a tall tale — that there is universal friendship now among hunters and the hunted. The cock has nothing to fear, the wily fox says. It’s a lie, of course.

So, the equally wily cock resorts to his own lie: he tells the fox that he sees greyhounds running towards them, surely with a message from the King of Beasts. The fox, outwitted, runs away in fear. So here we have two lies in a single story. The moral? “The best liars are often caught in their own lies.”

Children and their parents are quite comfortable surrounded by lies. Is Santa Claus a malicious or harmless lie?

Do you know the story of the Wizard of Oz? That classic U.S. movie about a young girl lost in a fantasy world, pursued by witches, struggling to go home? The entire plot relies on a deceit – a supposedly powerful wizard who is nothing more than a bumbling, ordinary conman, who uses magic tricks to make himself seem great and powerful.

Deceit at the service of entertainment.

Advertisements are often innocent exaggerations, fiction if you will in the service of business and profit-making. But sometimes ads can veer into falsehoods.

So fake news is not new. And we’re no strangers to lies. What does that mean for those of us interested in making the world a better place? Should we simply give up because the task is too great?

Hardly. The lesson is that truth is not black and white, but grey, and it’s a moving target.

Take, for example, colonialism. From the 15th century on, white Europeans conquered huge swathes of the Americas, Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Oceania. They subjugated millions of people, using brutal violence in many places to subdue indigenous populations. They brought diseases that wiped out millions.

They exploited natural resources, using native labor and pocketing most of the profit from sales into a global trading network that they established. By 1914, Europeans had gained control of 84% of the globe.

We know all of that now because colonized peoples have revolted against their colonial rulers and won independence. The wars of independence have been won, yet so many countries around the world are still grappling with the shameful effects of colonialism and racism.

The ambiguity of truth

But would everyone have agreed on that depiction of Europeans as rapacious colonialists before the wars of independence?

Certainly not most of the Europeans, who believed they were exporting a superior civilization to backward natives. Missionaries who led many colonial ventures believed they were doing God’s will by converting native populations to Christianity. And not a few natives turned a blind eye to atrocities and benefited financially.

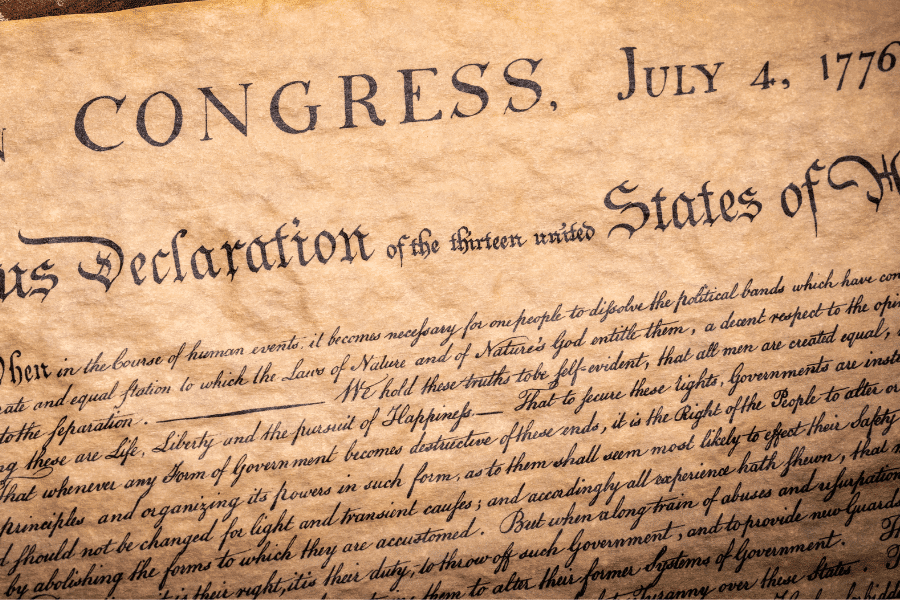

For a glaring example of the ambiguity of truth, take the United States. Its Declaration of Independence, borrowing from the French enlightenment, states that “all men are created equal,” with “unalienable Rights” to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” It put notions of freedom and equality at the heart of the American experiment. Yet it was written by a slave owner, Thomas Jefferson, and represented 13 colonies that all, to one degree or another, allowed slavery.

Convinced of their superiority and driven by an almost unquenchable appetite for wealth, white settlers drove Native Indians from their homes. The U.S. government authorized more than 1,500 attacks and raids on Indians. By the end of the 19th century, fewer than 238,000 indigenous people remained, down from some 5-15 million living in North America when Columbus arrived in 1492.

What is more, settlers in the South imported slaves from Africa, forcing them to work on vast plantations and denying them the very rights to life and liberty spelled out in the Declaration of Independence.

Rights and repercussions

Both Native Indians and African Americans are struggling to this day to come to terms with the treatment they suffered at the hands of the white colonials.

Would a white settler have seen himself or herself as a murderer? Hardly. In their minds, they were doing God’s work.

Mind you, the desire to colonize is not peculiar to Europeans. Imperial Japan and imperialist China both established overseas empires. The Empire of Japan seized most of China and Manchuria. To this day, Chinese nationals and South Koreans harbor ill feelings towards the Japanese. Chinese dynasties won control over parts of Vietnam and Korea.

There’s an expression in newsrooms around the world: “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” Put another way, the same individual might seem a terrorist to some, a hero to others.

Take Yagan, a 19th century indigenous Australian warrior from the Noongar people. He played a key role in early resistance to British colonial rule in an area that is now Perth. His execution by a young settler figures in Australian history as a symbol of the unjust treatment of indigenous peoples by colonial settlers.

A hero to his people, he was a murderer in the eyes of the British.

Different perspectives on history

Or take the Incan emperor, Atahualpa, who resisted the explorer and conquistador Francisco Pizarro, to this day a Spanish hero. Pizarro forced Atahualpa to convert to Christianity before eventually killing him, hastening the end of one of the greatest imperial states in human history.

How you view Pizarro may depend on where you are sitting and when you lived.

There are countless modern examples of radically different perspectives on events. Such discrepancies may be inevitable. Dogged journalists can shed light on events and protagonists, and help shape history – for better or for worse.

Joseph McCarthy was a U.S. senator who in the early years of the Cold War spearheaded a smear campaign against alleged Communist and Soviet spies. Only courageous reporting by a small group of journalists who dared question McCarthy’s tactics and risked being tarred as Communist sympathizers themselves led to McCarthy’s downfall.

Joseph McCarthy (L) with his attorney Roy Cohn, who later mentored Donald Trump (Wikimedia Commons)

The New York Times and Washington Post went out on a legal limb when in 1971 they published the Pentagon Papers, a U.S. government history of the Vietnam War that laid bare official lies that drove American policy for more than a decade in Southeast Asia.

The government called the man who leaked the government documents a criminal and sought to prevent the newspapers from publishing the damning revelations.

The newspapers won their case before the Supreme Court, and their reporting increased public pressure on the government to withdraw from Vietnam.

Watergate upended a presidency.

You’ve perhaps heard of Watergate? Literally speaking, it’s a hotel in Washington, DC. But it has come to stand for the dogged and courageous news reporting by two journalists with the Washington Post who exposed crimes by President Richard Nixon and helped lead to his resignation in 1974.

Courageous investigative journalism is hardly confined to the United States. A non-profit news outfit called AmaBhungane — in Zulu, “dung beetle,” an animal that digs through shit – has reported on corrupt business deals at the highest levels of South Africa’s government.

In the Arab world, investigative journalists in Egypt, Yemen, Tunisia, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Bahrain, Palestine, Mauritania, Algeria, Kuwait and Sudan have uncovered tax evasion, money laundering, drug smuggling, torture and slavery. They have unmasked doctors who have removed the wombs of mentally disabled girls with the consent of parents.

But it’s not all easy sailing. According to Freedom House, in 2017 there were only 175 investigative journalists in all of China, down 58% since 2011.

What does this mean for you, a young activist who wants to help change the world?

Truth is murky.

The lesson is that the truth may not lie squarely on one side or the other, but rather in a murky, grey area. It can take courage to shine a light in the shadows, teeming with lies. And you may have to hear viewpoints that differ radically from your own. It pays to listen.

Progress against racism, inequality and injustice depends on an informed public.

The best journalists recognize their responsibility to uphold the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which state that: all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights; and everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

As the third U.S. President Thomas Jefferson said: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

So stick up for your rights, including the right to free expression. Be fair. And remember that one man’s terrorist may be another man’s freedom fighter. You don’t have a lock on the truth.

Questions to consider:

1. Why is it important to understand that fake news is nothing new?

2. Do you think there is any way to stamp out fake news?

3. What does it mean to say, “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”?