Welcome to TWTQTW for June-September. Things were a little slow in July, but with back to school happening in most of the Northern Hemisphere sometime between last August and late September, the stories began pouring in.

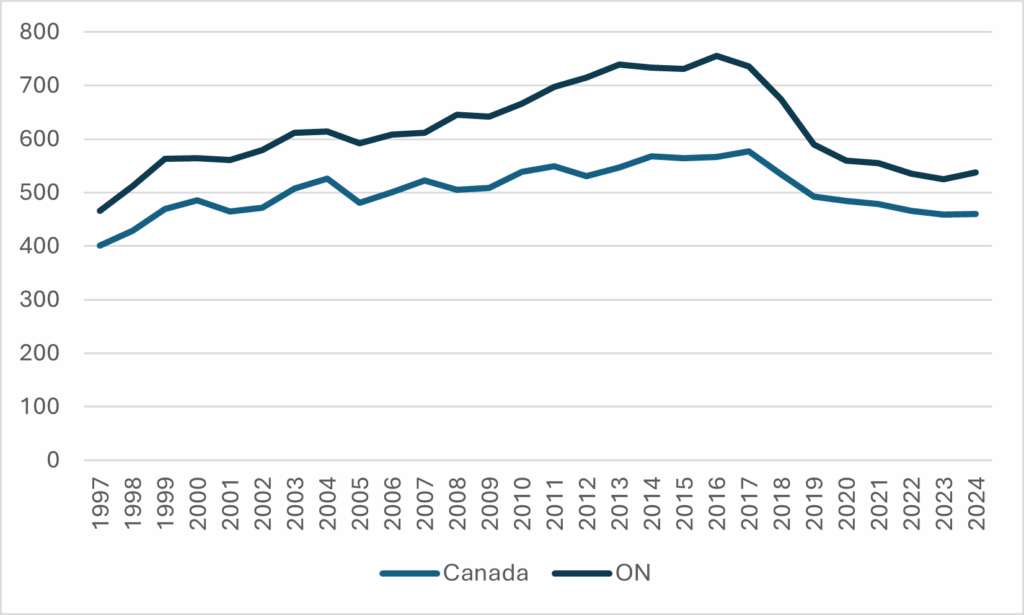

You might think that “back to school” would deliver up lots of stories about enrolment trends, but you’d mostly be wrong. While few countries are as bad as Canada when it comes to up-to date enrolment data, it’s a rare country that can give you good enrolment information in September. What you tend to get are what I call “mood” pieces looking backwards and forwards on long-term trends: this is particularly true in places like South Korea, where short-term trends are not bad (international students are backfilling domestic losses nicely for the moment) but the long-term looks pretty awful. Taiwan, whose demographic crisis is well known, saw a decline of about 7% in new enrolments, but there were also some shock declines in various parts of the world: Portugal, Denmark, and – most surprisingly – Pakistan.

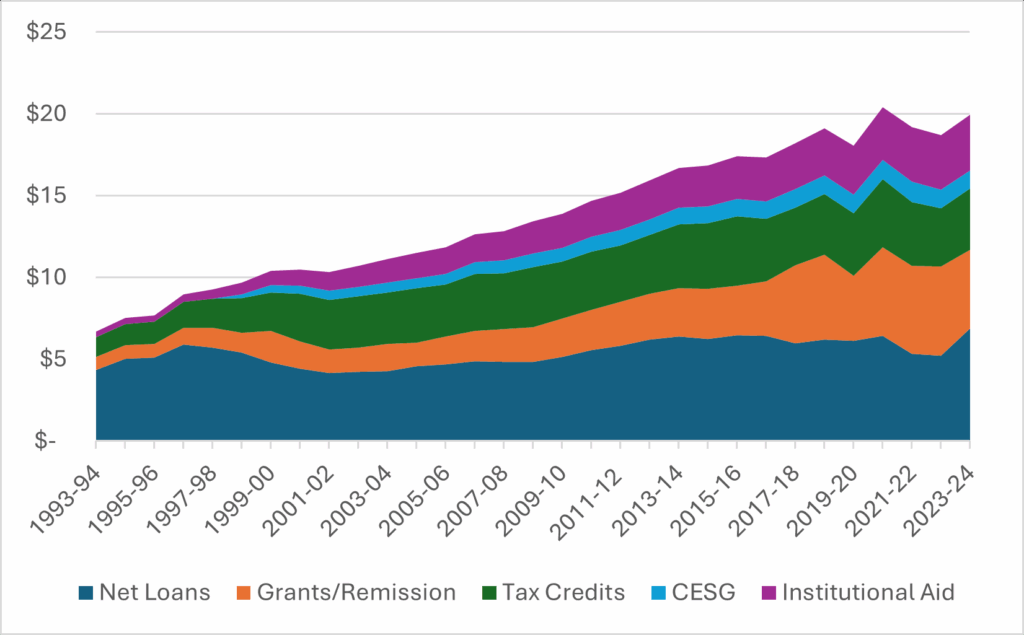

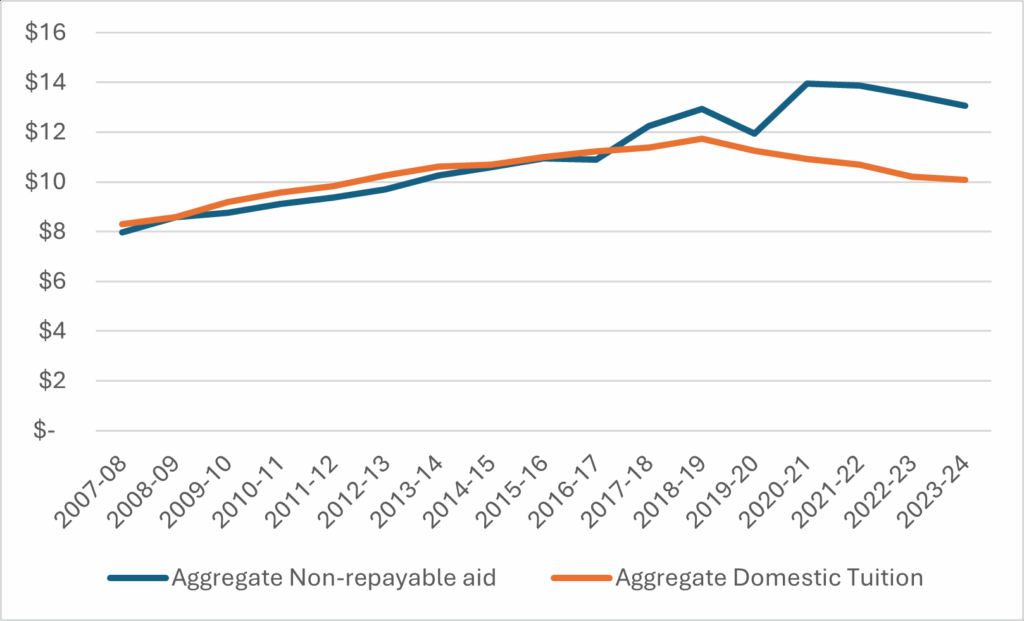

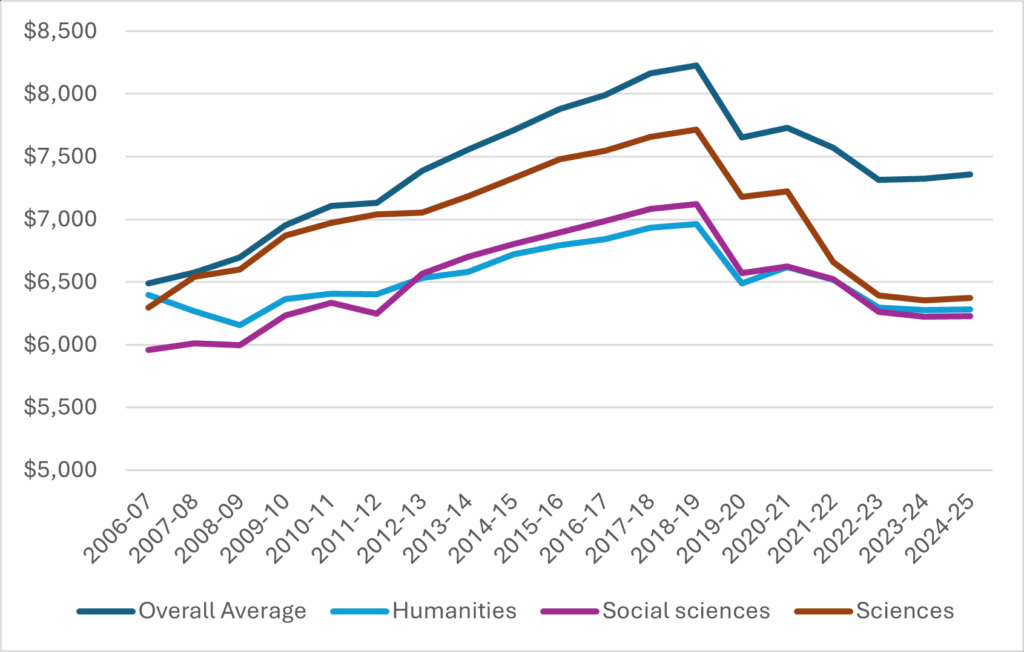

Another perennial back-to-school story has to do with tuition fees. Lots of stories here. Ghana announced a new “No Fees Stress” policy in which first-year students could get their fees refunded. No doubt it’s a policy which students will enjoy, but this policy seems awfully close in inspiration to New Zealand’s First Year Free policy which famously had no effect whatsoever on access. But, elsewhere, tuition policy seems to be moving in the other direction. In China, rising fees at top universities sparked fears of an access gap and, in Iran, the decision of Islamic Azad University (a sort-of private institution that educates about a quarter of all Iranian youth) to continue raising tuition (partly in response to annual inflation rates now over 40%) has led to widespread dissatisfaction. Finally, tuition rose sharply in Bulgaria after the Higher Education Act was amended to link fees to government spending (i.e. more government spending, more fees). After student protests, the government moved to cut tuition by 25% from its new level, but this still left tuition substantially above where it was the year before.

On the related issue of Student Aid, three countries stood out. The first was Kazakhstan, where the government increased domestic student grants increased by 61% but also announced a cut in the government’s famous study-abroad scheme which sends high-potential youth to highly-ranked foreign universities.

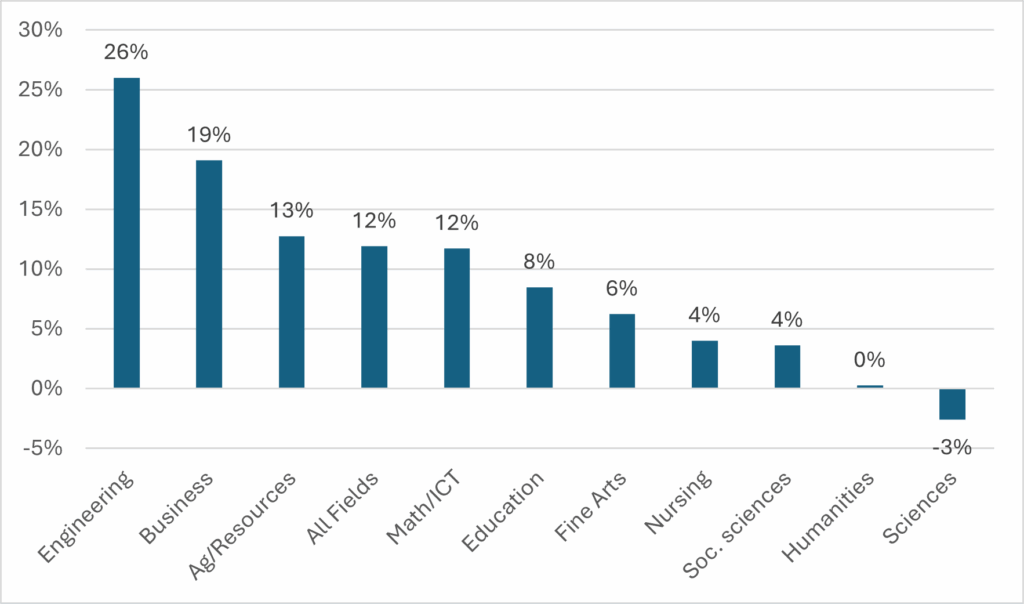

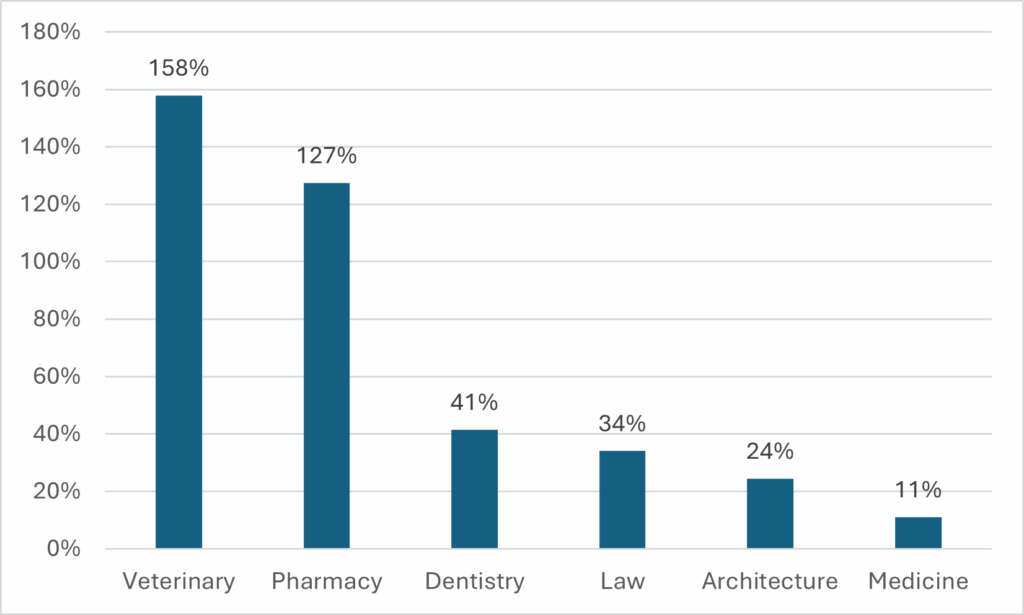

Perhaps the most stunning change occurred in Chile, where two existing student aid programs were replaced by a new system called the Fondo para la Educación Superior (FES), which is arguably unique in the world. The idea is to replace the existing system of student loans with a graduate tax: students who obtain funds through the FES will be required to pay a contribution of 10% of marginal income over about US$515/week for a period of twenty years. In substance, it is a lot like the Yale Tuition Postponement Plan, which has never been replicated at a national level because of the heavy burden placed on high income earners. A team from UCL in London analyzed the plan and suggested that it will be largely self-supporting – but only because high-earning graduates in professional fields will pay in far more than they receive, thus creating a question of potential self-selection out of the program.

In Colombia, Congress passed a law mandating ICETEX (the country’s student loan agency which mostly services students at private universities) to lower interest rates, offer generous loan forgiveness and adopt an income-contingent repayment system. However, almost simultaneously, the Government of Gustavo Petro actually raised student loan interest rates because it could no longer afford to subsidize them. This story has a ways to run, I think.

On to the world government cutbacks. In the Netherlands, given the fall of the Schoof government and the call for elections this month, universities might reasonably have expected to avoid trouble in a budget delivered by a caretaker government. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case: instead, the 2026 imposed significant new cuts on the sector. In Argentina, Congress passed a law that would see higher education spending rise to 1% of GDP (roughly double the current rate). President Milei vetoed the law, but Congress overturned President Milei’s veto. In theory, that means a huge increase in university funding. But given the increasing likelihood of a new economic collapse in Argentina, it’s anyone’s guess how fulfilling this law is going to work out.

One important debate that keeps popping up in growing higher education systems is the trade-off between quality and quantity with respect to institutions: that is, to focus money on a small number of high-quality institutions or a large number of, well, mediocre ones. Back in August, the Nigerian President, under pressure from the National Assembly to open hundreds of new universities to meet growing demand, announced a seven-year moratorium on the formation of new federal universities (I will eat several articles of clothing if there are no new federal universities before 2032). Conversely, in Peru, a rambunctious Congress passed laws to create 22 new universities in the face of Presidential reluctance to spread funds too thinly.

The newson Graduate Outcomes is not very good, particularly in Asia. In South Korea, youth employment rates are lower than they have been in a quarter-century, and the unemployment rate among bachelor’s grads is now higher than for middle-school grads. This is leading many to delay graduation. The situation in Singapore is not quite as serious but is still bad enough to make undergraduates fight for spots in elite “business cubs”. In China, the government was sufficiently worried about the employment prospects of the spring 2025 graduating class that it ordered some unprecedented measures to find them jobs, but while youth employment stayed low (that is, about 14%) at the start of the summer, the rate was back up to 19% by August. Some think these high levels of unemployment are changing Chinese society for good. Over in North America, the situation is not quite as dire, but the sudden inability of computer science graduates to find jobs seems deeply unfair to a generation that was told “just learn how to code”.

Withrespect to Research Funding and Policy, the most gobsmacking news came from Switzerland where the federal government decided to slash the budget of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) by 20%. In Australia, the group handling the Government’s Strategic Examination of Research and Development released six more “issue” papers which, amongst other things, suggested forcing institutions to choose particular areas of specialization in areas of government “priority”, a suggestion which was echoed in the UK both by the new head of UK Research and Innovation and the President of Universities UK.

But, of course, in terms of the politicization of research, very little can match the United States. In July, President Trump issued an Executive Order which explicitly handed oversight of research grants at the many agencies which fund extramural research to political appointees who would vet projects to ensure that they were in line with Trump administration priorities. Then, on the 1st of October (technically not Q3, but it’s too big a story to omit), the White House floated the idea of a “compact” with universities, under which institutions would agree to a number of conditions including shutting down departments that “punish, belittle” or “spark violence against conservative ideas” in return for various types of funding. Descriptions of the compact from academics ranged from “rotten” to “extortion”. At the time of writing, none of the nine institutions to which this had initially been floated had given the government an answer.

And that was the quarter that was.