Harvard officials wrote in financial statements that fiscal year 2025 “tested Harvard in ways few could have anticipated.”

Zhu Ziyu/VCG/Getty Images

Uncertainty has been the single most damaging aspect of the second Trump administration, professors have said, with university finances taking a hit despite the impact of many of the president’s cuts not yet coming to fruition.

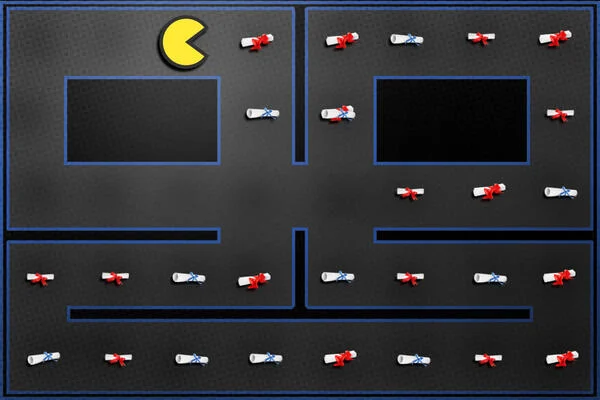

A year on since the U.S. president’s inauguration on Jan. 20, 2025, top universities are counting the cost of persistent attacks—which kicked off with significant cutbacks to federal research funding.

Although many of the harshest cuts have been quietly rescinded or blocked by the courts, universities have suffered considerable damage and are likely to face more systematic reforms to research in future, said Marshall Steinbaum, assistant professor of economics at the University of Utah.

“Beyond the high-profile, ideologically ostentatious cuts to some aspects of federally funded research, the whole enterprise is set to be less lucrative for universities going forward,” he told Times Higher Education.

Even though many of the cuts might not come to fruition, the uncertainty caused by having to plan for potential cuts had been the most damaging aspect, said Phillip Levine, professor of economics at Wellesley College.

“There’s still tremendous damage that’s been done, [but] the damage isn’t as extensive as it could have been.”

Levine said he was most worried about undergraduate international student enrollment, which often takes longer to feel the impacts of policy decisions.

Visa concerns were blamed for overseas student numbers falling by a fifth last year, but Harvard University recently announced a record intake, despite Trump’s attempts to ban its international recruitment.

But the institution did report its first operating deficit since 2020 in its financial statements—stating that the 2025 fiscal year “tested Harvard in ways few could have anticipated.”

The University of Southern California, the University of Chicago and Brown University also recorded sizable operating deficits.

Many institutions will suffer in the long term from a series of changes to student loan repayment. Trump has rolled back parts of the student loan origination system and introduced less generous income-based repayment plans and limits on federal loans, which will pose financial challenges to universities.

Recent research found that more than 160,000 students may be unable to find alternative sources of financing when the cap for loans kicks in later this year.

“The three-legged stool of higher education finance in the United States is tuition, federal research funding and state appropriations,” said Steinbaum. “All three legs have been cut down in the last year.”

As of Jan. 1, some wealthy universities also faced paying up to an 8 percent tax on their endowments, which could cost billions of dollars. Yale University has cited this additional burden for layoffs and hiring freezes.

Todd Ely, professor in the School of Public Affairs at the University of Colorado–Denver, said the traditionally diversified revenue portfolio of higher education had been weakened—which he said was particularly worrying because it coincided with the arrival of the “demographic cliff” and a hostile narrative around the value of a college degree.

Although highly selective and well-endowed private and public institutions will adjust more easily to the new environment, Ely said, “‘Uncertainty’ remains the watchword for U.S. higher education.”

“Research-intensive institutions, historically envied for their diverse revenue streams and lack of dependence on tuition revenue, have had their model of higher education funding thrown into disarray,” Ely added. “The battle for tuition-paying students will only increase, straining the enrollments of less selective and smaller private colleges and regional public universities.”

Robert Kelchen, professor and head of the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the University of Tennessee, said cuts within universities are mitigating some of the effects of these pressures.

Stanford University has announced $140 million in budget cuts tied to reduced federal research funding. There have also been budget reductions at Boston University, Cornell University and the University of Minnesota.

“The general financial challenges facing higher education prior to the Trump administration have not abated, and the cuts to federal funding have been notable,” said Kelchen.

But he is skeptical that deals with the White House, to which some institutions have committed, are the right way forward, because they can always be “pulled or renegotiated at a whim.”

“Universities need to try to get funding from other sources, such as students and donors,” Kelchen added, “but that is often easier said than done in a highly competitive landscape.”