by Carmen Cabrera and Ruth Neville

Generative artificial intelligence (GAI) tools are rapidly transforming how university students learn, create and engage with knowledge. Powered by techniques such as neural network algorithms, these tools generate new content, including text, tables, computer code, images, audio and video, by learning patterns from existing data. The outputs are usually characterised by their close resemblance to human-generated content. While GAI shows great promise to improve the learning experience in various disciplines, its growing uptake also raises concerns about misuse, over-reliance and more generally, its impact on the learning process. In response, multiple UK HE institutions have issued guidance outlining acceptable use and warning against breaches of academic integrity. However, discussions about the role of GAI in the HE learning process have been led mostly by educators and institutions, and less attention has been given to how students perceive and use GAI.

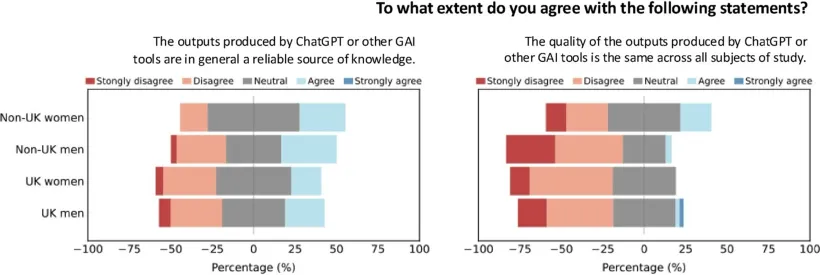

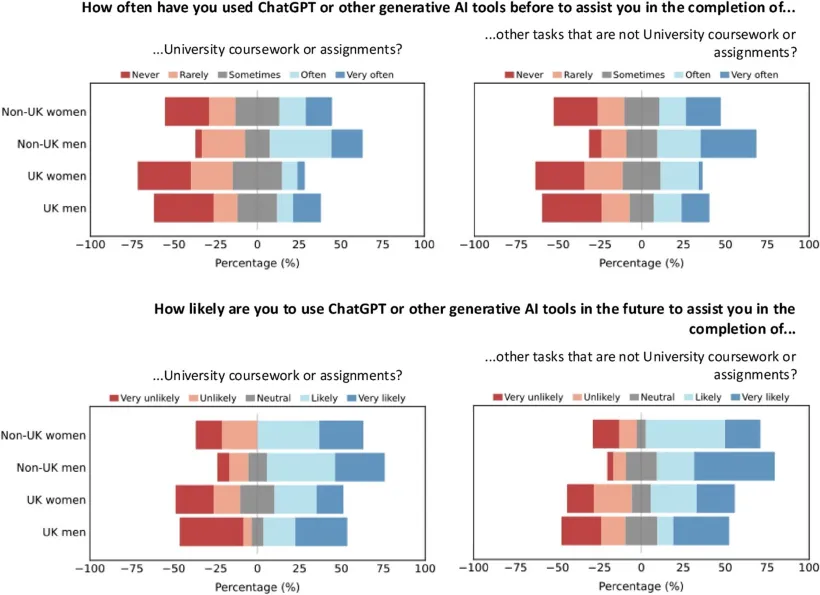

Our recent study, published in Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, helps to address this gap by bringing student perspectives into the discussion. Drawing on a survey conducted in early 2024 with 132 undergraduate students from six UK universities, the study reveals an impactful paradox. Students are using GAI tools widely, and expect their use to increase, yet fewer than 25% regard its outputs as reliable. High levels of use therefore coexist with low levels of trust.

Using GAI without trusting it

At first glance, the widespread use of GAI among students might be taken as a sign of growing confidence in these tools. Yet, when students are asked about their perceptions on the reliability of GAI outputs, many express disagreement when asked if GAI could be considered a reliable source of knowledge. This apparent contradiction raises the question of why are students still using tools they do not fully trust? The answer lies in the convenience of GAI. Students are not necessarily using GAI because they believe it is accurate. They are using it because it is fast, accessible and can help them get started or work more efficiently. Our study suggests that perceived usefulness may be outweighing the students’ scepticism towards the reliability of outputs, as this scepticism does not seem to be slowing adoption. Nearly all student groups surveyed reported that they expect to continue using generative AI in the future, indicating that low levels of trust are unlikely to deter ongoing or increased use.

Not all perceptions are equal

While the “high use – low trust” paradox is evident across student groups, the study also reveals systematic differences in the adoption and perceptions of GAI by gender and by domicile status (UK v international students). Male and international students tend to report higher levels of both past and anticipated future use of GAI tools, and more permissive attitudes towards AI-assisted learning compared to female and UK-domiciled students. These differences should not necessarily be interpreted as evidence that some students are more ethical, critical or technologically literate than others. What we are likely seeing are responses to different pressures and contexts shaping how students engage with these tools. Particularly for international students, GAI can help navigate language barriers or unfamiliar academic conventions. In those circumstances, GAI may work as a form of academic support rather than a shortcut. Meanwhile, differences in attitudes by gender reflect wider patterns often observed on academic integrity and risk-taking, where female students often report greater concern about following rules and avoiding sanctions. These findings suggest that students’ engagement with GAI is influenced by their positionality within Higher Education, and not just by their individual attitudes.

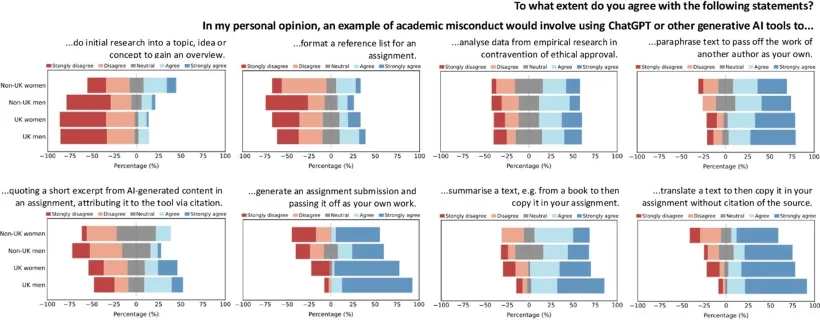

Different interpretations of institutional guidance

Discrepancies by gender and domicile status go beyond patterns of use and trust, extending to how students interpret institutional guidance on generative AI. Most UK universities now publish policies outlining acceptable and unacceptable uses of GAI in relation to assessment and academic integrity, and typically present these rules as applying uniformly to all students. In practice, as evidenced by our study, students interpret these guidelines differently. UK-domiciled students, especially women, tend to adopt more cautious readings, sometimes treating permitted uses, such as using GAI for initial research or topic overviews, as potential misconduct. International students, by contrast, are more likely to express permissive or uncertain views, even in relation to practices that are more clearly prohibited. Shared rules do not guarantee shared understanding, especially if guidance is ambiguous or unevenly communicated. GAI is evolving faster than University policy, so addressing this unevenness in understanding is an urgent challenge for higher education.

Where does the ‘problem’ lie?

Students are navigating rapidly evolving technologies within assessment frameworks that were not designed with GAI in mind. At the same time, they are responding to institutional guidance that is frequently high-level, unevenly communicated and difficult to translate into everyday academic practice. Yet there is a tendency to treat GAI misuse as a problem stemming from individual student behaviour. Our findings point instead to structural and systemic issues shaping how students engage with these tools. From this perspective, variation in student behaviour could reflect the uneven inclusivity of current institutional guidelines. Even when policies are identical for all, the evidence indicates that they are not experienced in the same way across student groups, calling for a need to promote fairness and reduce differential risk at the institutional level.

These findings also have clear implications for assessment and teaching. Since students are already using GAI widely, assessment design needs to avoid reactive attempts to exclude GAI. A more effective and equitable approach may involve acknowledging GAI use where appropriate, supporting students to engage with it critically and designing learning activities that continue to cultivate critical thinking, judgement and communication skills. In some cases, this may also mean emphasising in-person, discussion-based or applied forms of assessment where GAI offers limited advantage. Equally, digital literacy initiatives need to go beyond technical competence. Students require clearer and more concrete examples of what constitutes acceptable and unacceptable use of GAI in specific assessment contexts, as well as opportunities to discuss why these boundaries exist. Without this, institutions risk creating environments in which some students become too cautious in using GAI, while others cross lines they do not fully understand.

More broadly, policymakers and institutional leaders should avoid assuming a single student response to GAI. As this study shows, engagement with these tools is shaped by gender, educational background, language and structural pressures. Treating the student body as homogeneous risks reinforcing existing inequalities rather than addressing them. Public debate about GAI in HE frequently swings between optimism and alarm. This research points to a more grounded reality where students are not blindly trusting AI, but their use of it is increasing, sometimes pragmatically, sometimes under pressure. As GAI systems continue evolving, understanding how students navigate these tools in practice is essential to developing policies, assessments and teaching approaches that are both effective and fair.

You can find more information in our full research paper: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13603108.2025.2595453

Dr Carmen Cabrera is a Lecturer in Geographic Data Science at the Geographic Data Science Lab, within the University of Liverpool’s Department of Geography and Planning. Her areas of expertise are geographic data science, human mobility, network analysis and mathematical modelling. Carmen’s research focuses on developing quantitative frameworks to model and predict human mobility patterns across spatiotemporal scales and population groups, ranging from intraurban commutes to migratory movements. She is particularly interested in establishing methodologies to facilitate the efficient and reliable use of new forms of digital trace data in the study of human movement. Prior to her position as a Lecturer, Carmen completed a BSc and MSc in Physics and Applied Mathematics, specialising in Network Analysis. She then did a PhD at University College London (UCL), focussing on the development of mathematical models of social behaviours in urban areas, against the theoretical backdrop of agglomeration economies. After graduating from her PhD in 2021, she was a Research Fellow in Urban Mobility at the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), at UCL, where she currently holds a honorary position.

Dr Ruth Neville is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (CASA), UCL, working at the intersection of Spatial Data Science, Population Geography and Demography. Her PhD research considers the driving forces behind international student mobility into the UK, the susceptibility of student applications to external shocks, and forecasting future trends in applications using machine learning. Ruth has also worked on projects related to human mobility in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic, the relationship between internal displacement and climate change in the East and Horn of Africa, and displacement of Ukrainian refugees. She has a background in Political Science, Economics and Philosophy, with a particular interest in electoral behaviour.