Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As students returned to class earlier this month, Hawaiʻi schools reported the lowest number of teacher vacancies the state has seen in more than five years. As of last week, only 73 teacher positions were unfilled, compared to more than 1,000 in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

But schools are employing a growing number of unlicensed teachers, also known as emergency hires, to fill those vacancies. Last August, Hawaiʻi schools started the year with 670 emergency hires, an 80% increase from four years ago.

Emergency hires can work in schools for up to three years but must make progress toward earning their licenses.

The recent increase in emergency hires partly stems from state efforts to put more teachers in classrooms, including increasing pay for unlicensed educators in 2023. But while research shows that emergency hires tend to have higher retention rates, they may also be less effective than licensed teachers, who typically have more training and classroom experience.

While the Hawaiʻi teacher licensing board tracks emergency hires in schools, it doesn’t publish regular data on how many of these teachers go on to earn their teacher licenses and continue working in public schools here.

Even so, principals and researchers say hiring unlicensed teachers is better than leaving positions vacant, which can leave schools scrambling for substitutes. The state has also explored other options to recruit and retain educators, like raising teacher pay and bringing in workers from the Philippines, but some solutions may only be temporary.

“There’s a united front to attract qualified educators that are already certified,” said Chris Sanita, principal at Hāna High and Elementary. “I think it’s a larger state issue on housing and affordability.”

A Growing Population

In 2018, Brandon Galarita began teaching at Ke’elikōlani Middle School as an emergency hire, hoping to build on his experience as a substitute teacher and use his college degree in English. While the pay was low, Galarita said, working full-time as an emergency hire allowed him to earn a living while also completing the requirements for a teacher license.

“At least it starts building a teacher if they want to go into education,” said Galarita, who earned his license from the University of Hawaiʻi Mānoa in 2020. “I would hope that the influx of emergency hires will result in more teachers that are staying in the profession.”

Osa Tui Jr., president of the state teachers’ union, said he attributes the big jump in emergency hires to the pay raise they received two years ago. Currently, emergency hires earn about $50,300 a year, compared to $38,500 previously.

“These numbers reflect exactly what we were hoping to accomplish,” Tui said.

The state has encouraged prospective educators, including emergency hires, to earn their licenses through the Grow Our Own initiative at UH Mānoa, which helps cover the costs of tuition for teacher preparation programs. Teachers who complete the program and earn their licenses must work in public schools for at least three years.

Emergency hire numbers don’t always reflect teachers’ progress toward earning their licenses, said Waiʻanae Intermediate School Principal John Wataoka. While he has around 11 emergency hires on staff this year, only one of the teachers has yet to complete a teacher preparation program.

The rest have finished their training but are waiting to take a licensing exam or haven’t received the results of their final tests yet, Wataoka said.

“Right now, it’s just a waiting game,” he said.

But a recent study of emergency hires entering Massachusetts schools during the pandemic suggests that unlicensed teachers may be less effective than other educators. Students taught by emergency hires tended to have lower math and science test scores compared to their peers, according to research from the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research.

Jonathon Medeiros, a teacher at Kauaʻi High School and vice president of the Hawaiʻi Education Association, said he understands parents’ possible concerns about emergency hires and the quality of education students are receiving. But it’s still preferable to have an emergency hire in a classroom than a substitute — or nobody at all.

In the past, Medeiros said, students were occasionally sent to the library or cafeteria for study hall when there weren’t enough educators to teach every class and the state faced a shortage of substitute teachers.

Unlike emergency hires, DOE doesn’t require substitute teachers to have a college degree.

“We all want skilled, caring, talented teachers who are from the community and committed to their schools,” Medeiros said. “How do we make sure we get those people in every single classroom is the key question.”

Expanding The Pool

While the boost in emergency hire pay has attracted more teachers to public schools, the state is still searching for other solutions to increase the hiring pool.

At Waiʻanae Intermediate, Wataoka said he’s hired seven international teachers to fill staff positions over the past two years. The J-1 visa program, which DOE has participated in since 2019, allows teachers from other countries, primarily the Philippines, to teach in the state for up to five years.

This year, the department hired around 100 new teachers through the visa program, Superintendent Keith Hayashi said in a Board of Education meeting earlier this month. International teachers’ interest in working in Hawaiʻi is comparable to past years, he said, despite concerns that participation could drop after Immigration Customs and Enforcement agents raided the shared Maui home of teachers from the Philippines last spring.

On Maui, Sanita said he’s also seeing the impact of the bonuses introduced for teachers in hard-to-fill positions five years ago. While it’s difficult to attract people to Hāna — a town with limited housing and no stop signs – the $8,000 bonus for remote schools helps retain teachers who would otherwise struggle with the high cost of living, Sanita said.

“The differentials have really helped people, our teachers in Hana, not to have five different side hustles,” Sanita said. “They can actually teach and make ends meet.”

The bonuses have also incentivized teachers to remain at Waiʻanae Intermediate even when they face long commutes from other parts of the island, Wataoka said. While the Leeward Coast has the greatest concentration of new teachers in the state, the $8,000 bonus has helped experienced teachers cover the cost of gas to West Oʻahu and remain at Waiʻanae Intermediate.

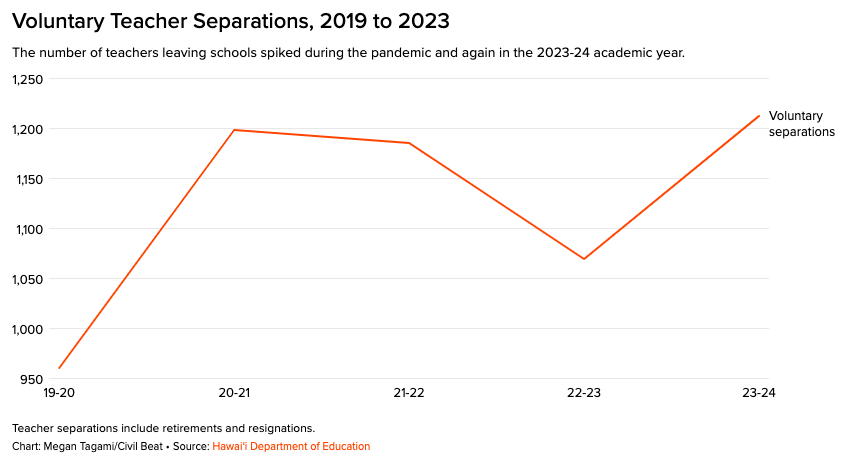

But despite more retention measures in place, the department saw a jump in the number of teachers leaving schools last year. Over 1,200 teachers voluntarily resigned or retired from DOE in the 2023-24 school year, compared to roughly 1,000 the year before.

Tui said there’s no single answer as to why the number of teachers leaving schools jumped. In some cases, teachers may have felt more comfortable changing jobs after the pandemic as they faced less uncertainty in the job market, he said.

This year, educators continuing to work in public schools will receive a 3% pay raise, with some veteran teachers receiving a larger raise of around 7%. While the pay increase will encourage teachers to stay in schools longer, Tui said, it’s possible the state will see a wave of educators retiring after three years as they qualify for higher state pensions.

For teachers hired before 2012, the state uses their three highest years of pay to determine their pensions.

“We have to make sure that we can get people into the profession that we can recruit to handle a drop off like that,” Tui said.

Civil Beat’s education reporting is supported by a grant from Chamberlin Family Philanthropy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter