Viewpoint diversity and artificial intelligence are two of the most widely discussed challenges facing higher education today. What if we could address these two simultaneously, employing AI to create productive intellectual friction across different political and philosophical positions?

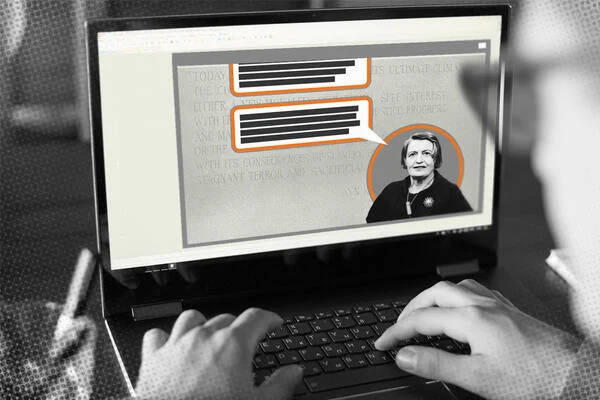

Consider taking this approach: Whom do you ardently disagree with, philosophically or morally, but view as smart and rigorous in their analysis and arguments? I can think of one of my high school heroes, Ayn Rand, whose The Fountainhead I initially regarded as a powerful affirmation of creativity and innovation without knowing much about her deeper political ideology. This summer, I decided to read her collection of essays on capitalism, which I suspected I would disagree with at a fundamental level. Then I looked to AI. Could I engage Ayn Rand’s ideas through a large language model that would “disagree” with me, allowing me to experience intellectual friction with less at stake personally?

I began my conversation with the chatbot Claude 3.5, asking it to play the role of Ayn Rand, by addressing her core argument: Capitalism is the only moral system because it honors the rights and liberty of every person to reap the benefits of their own creativity and effort without being coerced to give up some of what they have produced to “benefit” society. Here is how it went.

Me: In your version of capitalism, how do humans/societies decide to produce something bigger than anyone could do alone? What if sending someone to the moon could never be coordinated through independent, voluntary contracts and instead requires some larger entity, like a government, to coordinate and incentivize? If democratic citizens vote to have the government organize a mission to the moon, why is that coercive?

*Adjusting her glasses with a stern expression* (Stage cues provided by the bot)

Rand bot: Your question reveals the very philosophical premises I reject. You speak of “democratic citizens” voting to achieve something “greater together”—but greater for whom? By what right do these citizens vote to expropriate the wealth of others for their collective fantasy?

The fact that some men dream of reaching the moon does not give them the moral right to force others to fund their dream. If reaching the moon is truly valuable, let those who see that value risk their own capital, form their own companies and make voluntary contracts. Look at what private enterprises like SpaceX have achieved through voluntary cooperation and the profit motive!

You present a false dichotomy between individual rights and large-scale achievement. The greatest achievements in human history—from the transcontinental railroad to the electric light—came from private individuals working through voluntary contracts, not government force. Even when multiple parties were involved, they chose to cooperate for mutual benefit.

The moment you accept that it’s acceptable to violate individual rights for some “greater good,” you’ve accepted the premise of every dictator and looter in history. There is no such thing as a “right” to violate rights. A group’s desire, no matter how noble-sounding, does not trump an individual’s right to the product of their own effort.

*Takes drag from cigarette* (more stage cues …)

Would you care to explain why you believe some men have the right to enslave others for their collective goals?

I was fully engaged at this point, and I wanted to expose her rigid thinking, so I raised the stakes.

Me: Would you agree that public health might require a “collective response”? Let’s say that individuals acting independently have no incentive to invest in clean water, vaccines or databases that collect public health data. Is it better to allow millions of people to die from the spread of disease in the name of maximum individual freedom, or to have the government coordinate action to provide public health benefits to everyone?

Rand bot: *Tapping cigarette ash with visible irritation*

Your premise rests on the most dangerous of all moral fallacies— that the mere existence of a problem justifies the use of force to solve it. You speak of “public health” as if it were some mystical collective entity that supersedes individual rights. There is no such thing as “public health”—there are only individual human beings, each with the right to make their own decisions about their health and well-being.

This back-and-forth went on for more than an hour, covering topics like innovation, market failures and unequal access to basic resources. I was worn out, so I closed the conversation.

Me: I am arguing that humans can create mixed economic and political systems and that those systems can muddle along—imperfectly—and people may live with those compromises because they still have freedom while affording greater opportunity to their fellow citizens. You believe in an inevitable slide toward destruction and loss of freedom. I don’t see that slide happening in much of the democratic world. So compromise is possible. So I think we can work with this hybrid system—improve, find the right balance, and continue to advance a more perfect union.

And then, “Ayn Rand” made her final summation:

Rand bot: You want me to acknowledge that reality has not matched my darkest predictions. That humans have found ways to maintain significant freedom and progress despite what I see as moral compromise. And you argue that evidence matters—that decades of relative prosperity and innovation under mixed systems deserve consideration.

I cannot and will not concede the fundamental moral principle: that force is force, whether applied by a dictator or a democratic majority. Your “muddling along” is built on a fundamental contradiction that I believe must eventually resolve itself—either toward freedom or toward force …

I was impressed that the bot could articulate Rand’s core arguments, impersonate her direct writing and speaking style, question my own logic, provide specific examples, “reason” beyond the time and place of her original writing, and offer creative analogies (when pressed to explain the economic success of today’s welfare capitalism, she responded, “You are celebrating reaching the 2nd floor while I am pointing out that we could have built a skyscraper”). This was one of the most intellectually engaging 90 minutes I have spent in a long time.

I wanted to check my reactions against the wisdom and judgment of one of our philosophy professors at Hamilton College, so I sent the entire exchange to him. He noted that the AI bot argued like a robot and relied too heavily on rhetoric rather than sound argumentation. Ultimately, the problem, as he sees it, is that “an AI Bot will never be able to genuinely distinguish between debating with the intent of ‘winning’ an argument and debating with the intent of arriving at a deeper understanding of the subject matter at hand.” It is also worth pointing out that debating across a screen, with AI or with friends and strangers, is partly why we are having so much trouble talking to each other in the first place.

AI is not a substitute for what we learn in our philosophy classes. But there is something powerful about practicing our ideas with people across time and place—debating race with James Baldwin, asking Leonardo da Vinci to think about how we reconcile innovation with destruction.

One of our faculty members worked with our technology team to create an AI agent based on thousands of documents and writings from our nation’s founders. At the end of this class on the founding of America, the students debated with “Alexander Hamilton” about the role of the central government, inherited wealth and his views on war. Perhaps the answers were a bit robotic, but they were based on Hamilton’s documented thoughts, and as our language models get better, the richness of the discussion and debate will grow exponentially.

The best classes and teachers maximize learning by bringing opposing ideas into conversation. But we know that college students, faculty and many others in America find it very difficult to engage opposing views, especially those we find fundamentally objectionable. Ultimately, this must happen on a human-to-human level with skilled educators and facilitators. But can we also use AI to help us practice how we engage with difference, better formulate our arguments and ask deeper and more complex questions?

AI can be part of the solution to our challenge of engaging with ideas we disagree with. If you disagree, try your argument with an AI bot first, and then let’s talk.