The answer is not yet in. But since 2023, Bukele has doubled down on his project as the “world’s coolest dictator,” to quote a phrase he once used on his X profile. And he has won some high-profile admirers in the United States.

Bukele has repeatedly renewed his March 2022 state of emergency, which suspended constitutional guarantees and by definition is temporary. It has now been extended 39 times over three continuous years since inception. Bukele’s arrest tally, according to a report by human-rights watchdog Cristosal, is now up to at least 87,000 people — more than the death toll of the country’s 12-year civil war, which ended in 1992.

Bukele, who is still just 44, won re-election last year after sweeping aside term-limit restraints. A constitutional reform, approved by a pliant legislature, now empowers him to seek as many future terms as he wants.

A new kind of leader or more of the same?

Bukele’s embrace of digital public services, bitcoin and his tech-bro demeanor seems to suggest he wants to be thought of as a new, modern kind of leader. For all that, he is still following the path of many old-fashioned Latin American caudillos or strongmen before him.

State surveillance and pressure on human rights groups, corruption watchdogs and journalists have ramped up this year to such an extent that Cristosal has pulled its staff out of the country. Everyone, that is, except Ruth López, its lead anti-corruption investigator, who was arrested in May and is still being held on alleged embezzlement charges.

The Salvadoran Journalists Association has closed its offices too, and will operate from outside the country, following passage of a controversial “foreign agents” law in May which targets the finances of nongovernmental organizations receiving funds from abroad. Bukele’s government accuses many such groups of supporting MS-13. Since April 2023, the independent Salvadoran news outlet El Faro has been legally based in Costa Rica because of what it calls campaigns by the Bukele government to silence its voice.

“Autocrats don’t tolerate alternative narratives,” it said at the time. And still, the Trump administration likes what it sees.

Prisons and deportations

Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced on a February visit to El Salvador that Bukele had agreed to use his CECOT mega-prison to house criminals of any nationality deported from the United States — and even to take in convicted U.S. citizens and legal residents, too.

This proposed offshoring of part of the U.S. incarcerated population would be for a fee, Bukele clarified, that would help fund his own country’s prisons like the CECOT.

The United States then deported more than 200 alleged Venezuelan gang members as well as a group of alleged Salvadoran mareros to El Salvador. The Venezuelans were held at the CECOT until being sent home in a prisoner swap deal for a group of Americans held in Venezuela.

It would be illegal to deport a U.S. citizen for a crime, as Rubio seemed to acknowledge. “We have a constitution,” he observed. That didn’t stop Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem from visiting the CECOT in person and using the social media platform X to threaten “criminal illegal aliens” in the United States with being sent there:

“I toured the CECOT, El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center,” she posted. “President Trump and I have a clear message to criminal illegal aliens: LEAVE NOW. If you do not leave, we will hunt you down, arrest you, and you could end up in this El Salvadoran prison.”

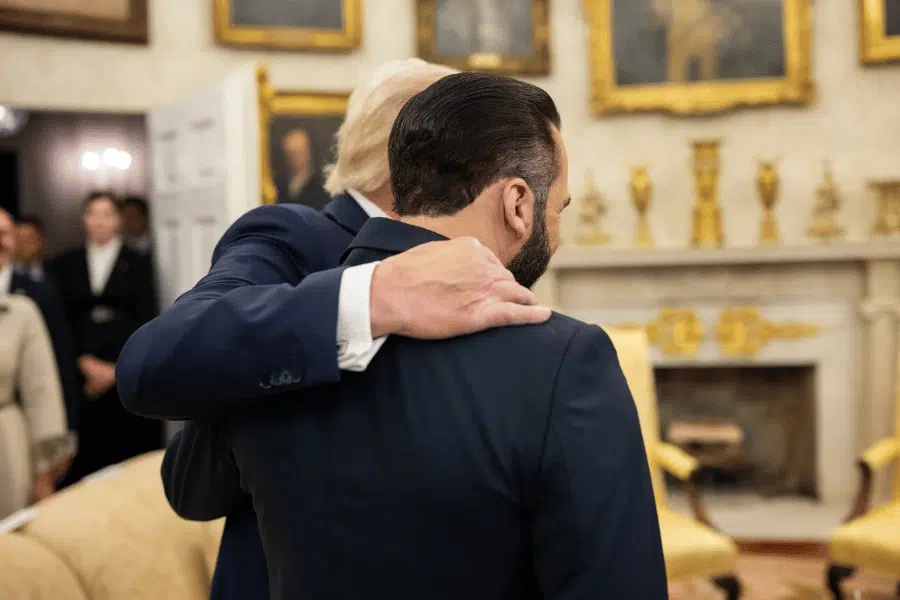

A visit to the White House

Bukele got to make a coveted visit to the White House in April. Trump praised Bukele’s mass imprisonment program, suggesting it could hold U.S. citizens next. Trump was captured telling Bukele on a live feed this: “Home-growns are next. The home-growns. You gotta build about five more places. It’s not big enough.”

The question is, how much of that was just grandstanding?

Like Bukele, Trump has made clear his disdain for constitutional limitations on his power, used government resources to go after his enemies, derided the freedom of the press and talked up domestic security threats to justify heavy-handed, authoritarian policing. The United States has a stronger tradition of democracy than El Salvador, to be sure.

Checks and balances exist. But the strongman playbook does not have too many variations. Ask Viktor Orbán in Hungary or Vladimir Putin in Russia or Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela.

It is not the first time El Salvador has darkly mirrored the fears and internal conflicts of the United States, be they about communism, immigrant crime or democracy. As I wrote in 2023, a straight line can be drawn from the Salvadoran military’s anticommunist violence against impoverished peasants in 1932 to the country’s bloody civil war, in which the United States backed a still atrocity-prone Salvadoran army against leftist rebels.

The line continues from that conflict to the emergence of MS-13, whose presence in the United States drives so much of the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant rhetoric today.

The birth of a global gang

MS-13 members are far from being innocent victims here, though Trump and his supporters have used their crimes to smear immigrants of all kinds. But it’s important to remember that the MS-13 gang, or mara, was formed by young Salvadoran immigrants in Los Angeles. As their home country spiraled toward civil war in the late 1970s, Salvadorans who fled to the United States found themselves threatened by Mexican and other gangs.

What started out as a weed-smoking, heavy-metal listening self-defense clique morphed in time into hardened criminals.

Their power grew when the U.S. government, making a highly visible statement about immigrant crime, deported members of MS-13 and other gangs to El Salvador in the mid 1990s, after the end of the civil war. Within a few years, the gangs ruled the Salvadoran streets. Violence soared in turf wars and government crackdowns. By 2015, gang-related violence made El Salvador the murder capital of the world.

From leading the world’s murder stats, it has now gone to leading the world’s incarceration stats under Bukele. El Salvador’s proportion of the population in prison is now three times that of the United States, which is no slouch when it comes to incarcerating its people (it ranks fifth).

Of course, Salvadorans are entitled to freely elect whomever they want as president, as are U.S. citizens. Both Bukele and Trump won their elections and are doing in office exactly what they said they would do. Yet populist authoritarians have a way of clinging to power and confusing their own needs and egos with the state.

They brook less contradiction and dissent over time. I, for one, hope the increasingly dystopian utopia Bukele is building in his homeland remains just a cautionary tale in El Salvador’s fraught and symbiotic relationship with the United States.

It should not be an inspiration.

Questions to consider:

1. Why might some a majority of people in a country accept rule by a dictator?

2. What is one example of the close relationship between El Salvador and the United States?

3. Do you think that eliminating basic judicial rights can be justified in fighting crime?