This blog was kindly authored by Dr Fadime Sahin, Senior Lecturer in Accounting and Finance at the University of Portsmouth, London.

According to the latest available data, approximately 264 million students worldwide were enrolled in higher education in 2023. Reasons for attending include the desire to acquire knowledge and skills, enhance employment prospects, boost social mobility and contribute meaningfully to society. Nearly three million students were enrolled at UK higher education institutions in 2023/24 (the most recent figures).

The role of universities is increasingly debated across public discourse, shaping policy documents and household discussions, considering the tension between traditional academic skills, employability demands, sustainability imperatives and the accelerating influence of AI. The skills agenda currently sits at the heart of policymaking in England due to the skills gap facing the UK. The Lifelong Learning Entitlement, a flagship UK policy initiative that was introduced as a central plank of this agenda, seeks to expand access to flexible, modular study across a lifetime, reinforcing the policy emphasis on reskilling and employability.

In a recent HEPI blog, Professor Ronald Barnett argued that policy discourse speaks almost exclusively of skills (employability, reskilling, skills gap) – the new currency of education – moving away from education and knowledge acquisition; while academic discourse speaks of education, but rarely of skills, especially in the humanities and social theory, resulting in a polarised and disconnected debate.

Dr Adam Matthews, in another HEPI blog, echoed that policy discourse has become increasingly concerned with doing (skills) rather than knowing (knowledge). He analysed both the Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper and TEF (2023) submissions and found a similar imbalance: ‘skills’ outnumbered those to ‘knowledge’ by a ratio of 3.7, even higher among large, research-intensive universities that might be expected to focus more on knowledge production. The Post‑16 Education and Skills White Paper used the word ‘skills’ 438 times, but ‘knowledge’ only 24. The shift has been shaped by economic and growth imperatives, accountability and the instrumental role of universities for economic and social engineering, however it also risks eroding universities’ identity as knowledge producers. The same pattern is evident in the WEF’s Defining Education 4.0: A Taxonomy for the Future of Learning, which references ‘skills’ 178 times, but ‘knowledge’ only 32.

In a blog post, Professor Paul Ashwin cautioned that a tertiary education system built only on skills, without knowledge, will deepen inequality and suggested a knowledge-rich understanding of skills. He stressed that skills without knowledge are hollow and insufficient, because they lack the contextual and disciplinary knowledge that makes them meaningful and adaptable. He pointed out that the Skills England report champions skills, but offers little clarity on what they actually mean. The listed skills (teamworking, creative thinking, leadership, digital literacy, numeracy, writing) are generic and detached from a specific context.

The knowledge society was built on this promise. Yet in a post-truth era, that promise is faltering. Over the years, the emphasis on knowing – the pursuit of structured, disciplinary knowledge – has diminished, eroded by information overload, easy accessibility, erosion of trust in experts and an increasing policy focus on application and skills, even before the advent of AI. This decline sets the stage for Ashwin’s concern that a skills‑only system risks becoming hollow and inequitable.

Understanding skills

Amid this tension, it is useful to trace how different categories of skills have been constructed and prioritised within higher education.

Hard skills

Over the decades, hard skills have dominated classrooms, a result of education systems built around industrial-era priorities, reinforced by measurability bias through standardised testing and the privileging of tangible qualifications. These skills refer to technical, tangible, quantifiable, job-specific and measurable abilities that are closely linked to knowledge acquisition and reflected in formal qualifications. Hard skills include coding/programming, engineering, data analysis, bookkeeping/accounting, foreign languages and other technical and occupational skills. Yet, the balance has shifted in recent decades as employers and policymakers emphasise 21st‑century competencies, including soft skills, green skills, digital and global skills and now increasingly AI skills. The fastest-growing skills (AI) category in higher education did not exist in mainstream curricula three years ago.

Soft skills

Soft skillshave long been undervalued and sidelined in classrooms. Strikingly, the term itself was first formalised not in education by the U.S. Army in 1972, when the Continental Army Command defined interpersonal and leadership capabilities as ‘soft skills.’ What began as military doctrine has since become central to employability discourse. Soft skills are interpersonal, intangible, non‑technical, transferable and context‑dependent abilities. They are closely linked to personal attributes and social interaction and reflected in behaviours, relationships and adaptability rather than formal qualifications. Soft skills can be categorised as personal qualities and values; attitudes and predispositions; methodological and cognitive abilities; leadership, management and teamwork; interpersonal capabilities; communication and negotiation; and emotional awareness and labour.

Digital skills and AI literacy

Computer literacy emerged in the 1980s and 1990s; with the spread of the Internet, this evolved into digital literacy, which in turn laid the foundation for today’s broader category of digital skills. The digital revolution prompted reforms. The core 21st-century digital and global skills include technical proficiency, information literacy, digital communication and networking, collaborative capacity, creativity, critical thinking, problem‑solving, intercultural understanding, emotional self-regulation and wellbeing. Since the end of 2022, the rapid uptake of generative AI tools has further expanded this landscape, introducing new forms of AI literacy and human-AI collaboration as essential competencies.

Green skills

Beyond interpersonal competencies, sustainability imperatives have introduced a new category: green skills. Green skills have emerged as a central focus in policy frameworks, driven by growing awareness of climate change, environmental degradation and the imperative of sustainability. Green skills refer to ‘the knowledge, abilities, values and attitudes needed to live in, develop and support a society which reduces the impact of human activity on the environment’, together forming green human capital. Green competencies are increasingly linked not only with green jobs, but with the broader transition toward sustainable economies. Green skills include technical and practical (heat pump installation, domestic recycling, energy grid engineering, peatland restoration), enabling skills (project management, collaboration, public engagement, digital skills) and knowledge and attitudinal capacities (carbon and climate literacy, systems thinking, environmental stewardship).

Mad skills

Alongside sustainability imperatives, a newer emergent HR discourse is the so‑called ‘mad skills’ – unconventional, disruptive and non-linear thinking or experiences in a rapidly changing labour market. Mad skills stem from personal passions, hobbies, creative ventures or extraordinary experiences or resilience stories. Although mad skills haven’t found its place in academic literature, it might have become part of the vocabulary of recruiters.

Taken together, these categories illustrate the expanding and overlapping landscape of skills. Yet the very language we use to describe them is increasingly problematic. The label ‘soft skills,’ for instance implies that they are secondary, less important or less measurable than ‘hard’ skills, which risks undervaluing them. As AI increasingly automates hard skills (coding, data analysis, translation), the distinction begins to blur. What remains uniquely human – empathy, judgement, creativity – becomes central, better captured by the term ‘human skills.’ After all, we may end up dealing only with human skills and human‑AI collaborative skills.

The role of the university

Hard, soft, green, digital, global, AI… the list keeps expanding. Today’s workplace pressures candidates to master them all to stand out. These categories are overlapping and often co-developed. Universities, increasingly framed as providers of every imaginable skill, risk being reduced to training centres. When universities behave like training centres, the focus of education shifts from broad academic exploration, research and innovation to specific, narrowly vocational skill acquisition, designed for immediate employment needs. In the process, their identity as institutions of knowledge and civic purpose begins to erode. The problem is not the existence of these skills, but their policy dominance as output metrics. It is important to recognise that universities have historically embedded broad, intellectual and transferable capabilities alongside disciplinary knowledge; the current shift is toward narrow, vocational, immediately marketable packages. Cross-cutting skills are valuable when embedded within knowledge-led curricula, not as substitutes for knowledge production.

Yet employment needs are never static. The skills taught today may lose relevance within five or ten years after graduation, with AI expected to further compress the lifespan of many skills. Universities will inevitably try to keep pace with the ever-evolving skills agenda, but graduates may still find themselves holding qualifications in skills that have become obsolete, even more so now with AI. This emphasis places considerable weight on cross-cutting competencies such as soft skills, green skills, digital/AI literacy and global awareness.

However, in certain disciplines, e.g., accounting and finance, the accreditation requirements of major professional bodies (ACCA, CIMA, ICAEW) remain heavily exam‑driven, privileging technical knowledge and hard skills while leaving only a limited scope for the development of broader competencies. Universities do adjust, increasingly embedding diverse skills alongside technical skills, but structural constraints, sometimes necessary, remain.

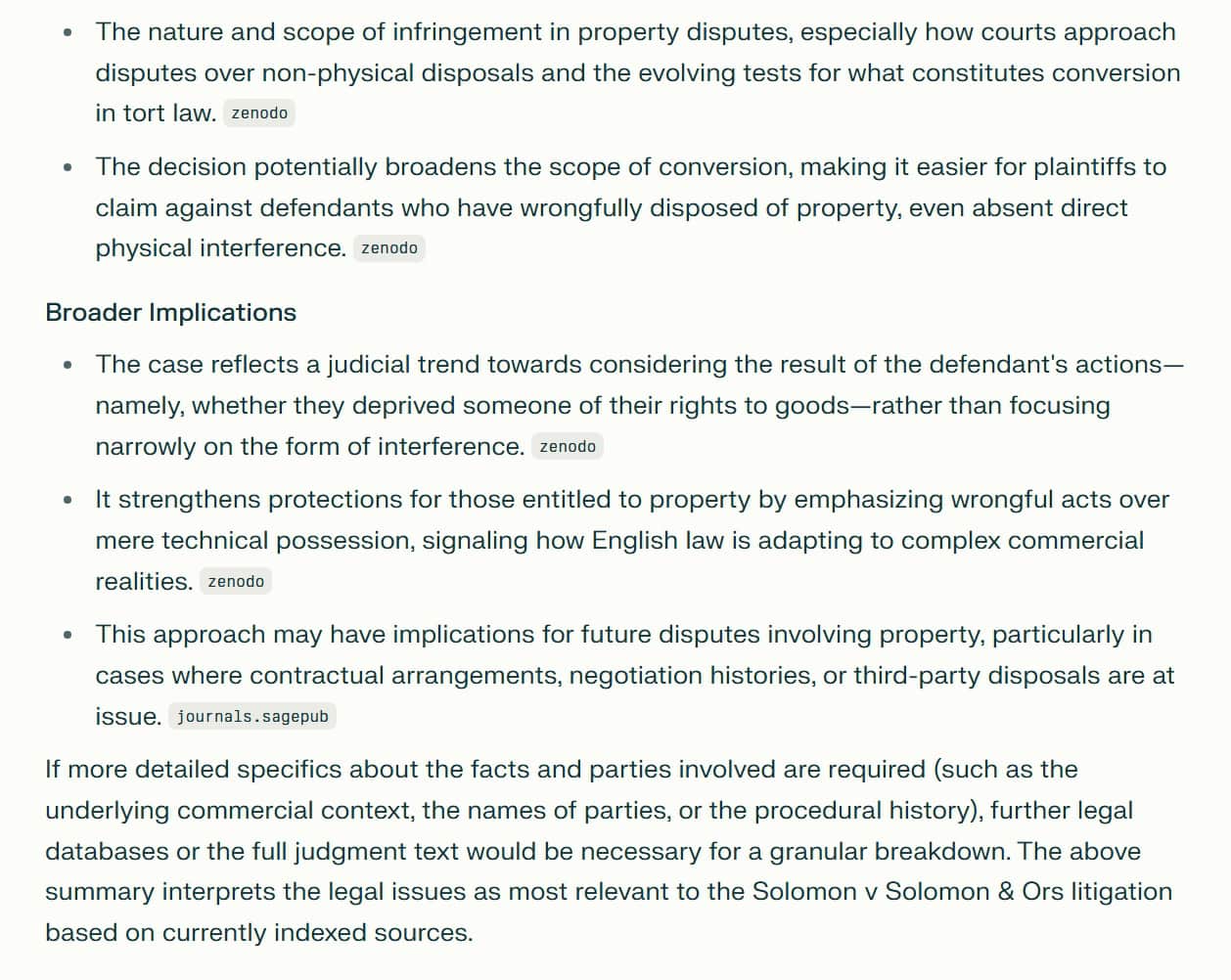

Changing student landscape adds a layer to this dynamic. HEPI’s 2025 Student Academic Experience Survey shows that almost 70% of full-time students in the UK – 65% of home students and 77% of international students – are engaged in paid employment during the academic term. More students are trading off study time for work to manage financial pressures. Students are now expected to master more skill categories than any previous generation, with less time to learn them. Universities must therefore navigate not only the shifting skills agenda, but also the reduced availability of students for independent study – and, in some cases, even class attendance – to develop these skills.

Amid these pressures, universities are increasingly judged by the employment status of their graduates, yet such measures often ignore the realities of the job market, particularly for the young. A mismatch arises when well-prepared graduates with relevant skills remain unemployed, underscoring that graduate outcomes alone are not a reliable proxy for educational quality. In fact, the latest Graduate Labour Market Statisticsshow that only 67.9% of graduates in England were in high-skilled jobs in 2024. Nearly a third were in roles not requiring graduate-level skills. The proportion of graduates in high-skilled employment has hovered around 65–67% for a decade (2015-2024). The 2024 figure (67.9%) is the highest in the series, but only marginally above previous years. This pattern is not new. High-skilled employment rates for graduates were 69.5% in 2006, 67.3% in 2009, 65.3% in 2012 and 66.2% in 2015. In other words, for nearly two decades, the proportion of graduates entering high-skilled roles has remained stubbornly flat. This persistent underemployment, despite years of skills-focused reform, may challenge the assumption that expanding skills provision alone can resolve graduate underemployment.

Universities find themselves caught between competing pressures: policymakers emphasising immediate employability skills; students juggling financial pressures and limited study time; and labour markets struggling to provide suitable graduate opportunities.

This tension ultimately circles back to the principle of lifelong learning. We need to recognise that education cannot be reduced to a finite set of skills, but must remain a continuous process of adaptation, renewal and knowledge creation.

Faced with the skills squeeze, it seems increasingly likely that ‘human skills’ and ‘human‑AI collaborations’ may matter most.