The mainstreaming of disruptive technology is a familiar experience.

Consider how quickly contactless payment has become largely unavoidable and assumed for most of us.

In a similar way, we are already seeing how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is, even more rapidly, weaving itself into the fabric of education, work, and wider society.

In higher education’s search for appropriate responses to the rise of GenAI, much of the emphasis has focused on the technology itself. Yet, as machine learning becomes increasingly embedded in everyday tools and student learning practices, we suggest that this brings new urgency to making the ongoing value of human learning visible. Not to do so risks leaving universities struggling to explain, in an era of increasingly invisible GenAI, what is distinctive about higher education at all.

A revealing weakness

Our starting point for a meaningful response to this has been a focus on critical thinking. For a long time, institutions have expressed the importance of students developing as capable critical thinkers through high-level signifiers like graduate attributes, employability skills, and course learning outcomes. But these often substitute for shared understanding, signalling value without making it visible. The rise of GenAI does not challenge critical thinking so much as it reveals our existing weakness in articulating its substance and connection to practice.

If we were to ask you what critical thinking meant to you, what would you say? And would your students think the same? Through a QAA-funded Collaborative Enhancement Project with colleagues from Stellenbosch University, we have been asking teachers these same questions. While each person we spoke to was quick to value it as an essential learning outcome, we were struck by the extent to which staff acknowledged how little time they had spent reflecting on what it meant to them.

Through extended conversations with colleagues from our two universities we were able to explore what critical thinking meant in a range of disciplines, and to capture the diverse richness of associated practices, from a search for truth, a testing of beliefs, and an openness to critique to systematic analysis and structured argumentation.

The right answer?

Colleagues also identified both strengths and barriers in students’ engagement with critical thinking. Some highlighted students’ social awareness and willingness to experiment, while others noted that students often demonstrate criticality in everyday life but struggle to transfer it to academic tasks. Barriers included a tendency to seek “right answers” rather than engage with ambiguity. As one lecturer observed, “students want the correct answer, not the messy process”. Participants also reflected on the influence of GenAI, with some warning that this technology “gives answers too easily” – allowing students to “skip the hard thinking” – while others suggested it could create space for deeper critical engagement if used thoughtfully.

From the student perspective, surveys at both institutions also revealed broadly positive perceptions of critical thinking as an essential graduate capability, with respondents articulating their belief in its long-term value including in relation to GenAI, but expressing uncertainty as to how such skills were embedded in their programmes.

The depth of staff responses demonstrates that a collective wellspring of understanding exists. What we need to do more is find ways to bring this to the surface to inform teaching and learning, communicate explicitly to students, and give substance to the claims we make for higher education’s purpose.

With this practical end in mind, we used our initial findings to develop a Critical Thinking Framework structured around three interrelated dimensions: Critical Clarity, Critical Context, and Critical Capital. This framework supports educators in identifying the forms of critical thinking they wish to prioritise, recognising barriers that may inhibit its development, and situating these within disciplinary and institutional contexts. It serves both as a reflective tool and a practical design resource, guiding staff in creating learning activities and assessments that make human thinking processes visible in a GenAI-rich educational landscape. This framework and a set of supporting resources, along with our full project report, are now available on the QAA website.

The slowdown and the human factor

By working with educators in this way, we have seen the adoption of approaches that slow learning down, providing space to support reflection and make the mechanics of critical thinking more visible to learners. Drawing on popular culture through the use of materials that are familiar to students, such as advertising, music and film, has been used as an approach to reduce cognitive load, enabling learners to focus on actually practising thinking critically in ways that are more visible and explicit.

Having put this approach into practice, the feedback received across both institutions suggests that our framework not only supports staff in designing effective approaches to promote critical thinking but also gives students opportunity to articulate what it means to them to think critically. As students and staff have been given the opportunity to pause and reflect, it has underpinned meaningful awareness of the value of the human component in learning.

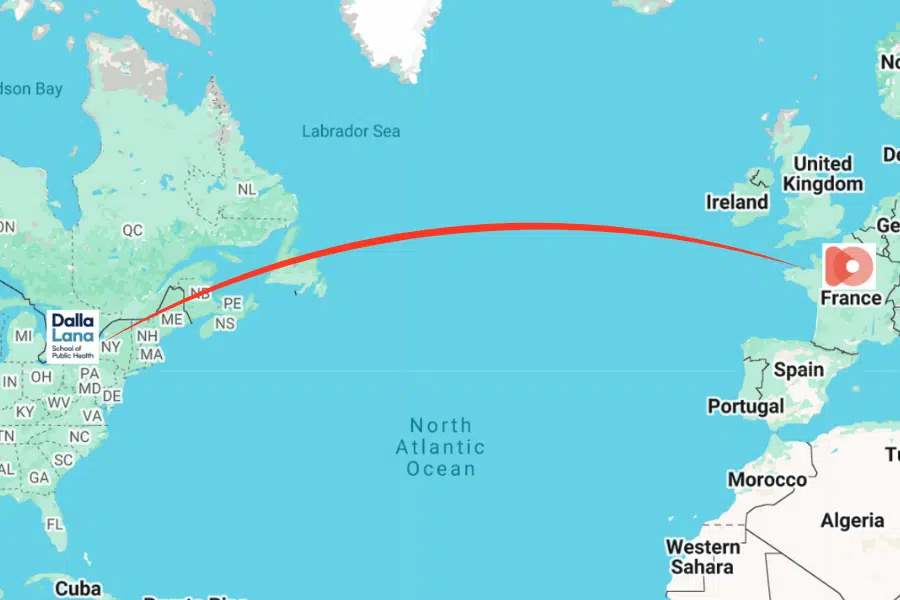

The growth of GenAI has disrupted the higher education sector and challenged leaders and practitioners alike to think differently and creatively about how they prepare graduates for the future. As an international collaboration, this project has reinforced the view that this challenge is not limited to any single institution, and that there is much to be gained from fostering shared understanding. The results have reminded us that effective solutions can include those that are low-cost and low-risk, simple and practical.

GenAI makes visible what universities have left implicit for too long. Higher education needs to slow down, not to resist GenAI, but to better articulate and advocate for human learning.

Join us at The Secret Life of Students on Tuesday 17 March at the Shaw Theatre in London to keep the conversation going about what it means to learn as a human in the age of AI.