Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This has been an especially challenging year for Rosalba Ortega’s family.

It’s been a cold, soggy winter in Bakersfield, and Ortega said her two granddaughters, ages 4 and 7, don’t have warm coats for their walk to school. Rent and food prices have been climbing, and as a farmworker, she’s struggled to find work in the fields. Last month’s delays to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) — known in California as CalFresh — hit her grandkids at a time when her family is already struggling to put food on the table.

“There’s not much food for them,” said Ortega, in Spanish. “We have to look for low prices to buy for them. Sometimes the shelters give us food and that helps us a lot.”

Ortega said her family never had to rely on shelters and churches for food in the past, but this year has been different.

She isn’t alone. Disruptions to SNAP amid the government shutdown last month came at a time when California families say they are increasingly struggling to meet basic needs, including putting food on the table.

Three in 10 Californians — and half of lower-income residents — say they or someone in their household has reduced meals or cut back on food to save money, according to a survey conducted in October by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California.

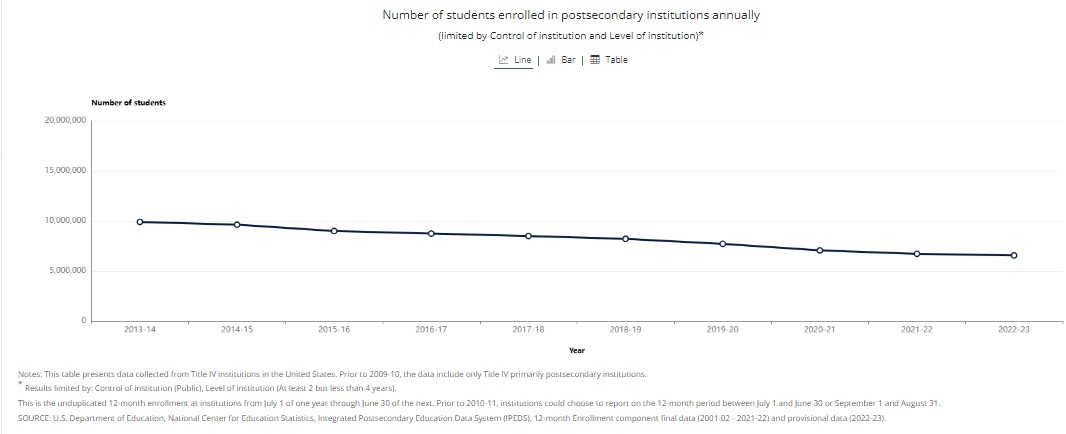

Experts say that hunger and economic distress can affect students’ academic performance and determine whether they decide to attend — or finish — college.

“What’s happening out of school can have a huge impact on their ability to learn while they’re in school,” said Natalie Wheatfall-Lum, director of TK-12 policy for EdTrust-West, a nonprofit that advocates for justice in education.

Research shows children struggle to pay attention at school when SNAP benefits run out mid-month, and families turn to ultra-processed foods, according to Martin Caraher, a food policy expert at City University London who has worked with the World Health Organization.

“You see it in behavior and performance at school,” Caraher said.

Federal cuts reduce food aid

President Donald Trump’s budget and tax bill, passed by Congress in July, made cuts to SNAP and Medicaid, called Medi-Cal in California. California’s low-income students and their families will likely see federally funded food support and health care shrink or vanish under the law.

This is coming at the same time that the Trump administration says it wants to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education to “break up the federal education bureaucracy and return education to the states,” a move that conservatives have long advocated since the creation of the Cabinet-level department in 1979.

Wheatfall-Lum said that the federal government has been making cuts and laying off staff at programs aimed at those who are already hardest hit by hunger and economic distress, such as migrant students, multilingual students, homeless students, and students of color.

In its upcoming budget cycle, California should address the needs of families — both in and outside of education, she said.

“What the state can do is make sure not to back away from programming in place to support these same students,” Wheatfall-Lum said.

EdTrust-West is advocating for the state to continue its commitment to a school funding formula that offers extra support to schools to help low-income and vulnerable students. Continuing to fund the community schools model is especially important, she said, because it is more responsive to families’ needs.

Families with young children hit hard

The number of struggling California parents with young children is especially alarming, researchers say. Nearly 3 in 4 families in California with children under age 6 report struggling with one or more basic needs, such as utilities, housing, food, health care and child care, according to the RAPID California Voices survey conducted in July.

The project, conducted by Stanford University, has been surveying parents and caregivers with young children since November 2022. During that time, more than half of families surveyed said they struggled with basic needs, but over the last year, struggles with health care, food and utilities reached 73% — one of the highest levels since the survey began.

“It’s pretty stark data,” said Philip Fisher, director of the Stanford Center on Early Childhood. “Our research shows consistently that economic hardship translates subsequently into parent stress and distress, which then gets passed along to child distress. So if you want to know how kids are doing, these are not great trends.”

Fisher noted that supports rolled out during the pandemic, such as the expanded Child Tax Credit, increased SNAP and WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) benefits, and stimulus checks, resulted in fewer parents of young children experiencing material hardship and emotional distress. As those benefits expired, that trend reversed, he said.

Researchers at Stanford asked caregivers to explain the biggest current challenges for their family in their own words. They shared those anonymized answers with EdSource.

“We’re working hard, but it’s not enough anymore,” wrote one caregiver in San Joaquin County. “We need our leaders to understand that even full-time workers can’t afford rent, health care, and food in this state. Wages haven’t kept up.”

One caregiver in San Bernardino County said they are worried about how the cuts from Trump’s budget will affect their Medi-Cal and CalFresh benefits.

“They might get cut because the [Big Beautiful Bill] passed,” the caregiver wrote.

College students struggle with basic needs

College students are also struggling — and unlike K-12 students who receive breakfast and lunch at school, they don’t have guaranteed meals.

Typically, students come into Long Beach State’s Basic Needs center because of a specific crisis, such as losing their job, said the center’s director, Danielle Muñoz-Channel. But now, students tend to come in just because they’re getting squeezed all around by rent, utilities and food prices.

“They can’t pinpoint any one factor,” she said. “We ask what changed, and they say, ‘Nothing, I just can’t afford it anymore.’”

Muñoz-Channel said she’s monitoring whether federal cuts to CalFresh and Medi-Cal benefits, such as tightened work requirements, could affect students and the future workforce. She said students need to have their basic needs met so that they can focus on school — otherwise they risk not graduating on time or not finishing their degree at all.

“I’m worried about how it will affect our most needy students who use college to break generational cycles of poverty,” she said.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how