This is part two of a two-part series on the 50th anniversary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. For part one, click here.

Special education staff turnover is a constant challenge at Godwin Heights Public Schools in Michigan.

Sometimes a special education role will turn vacant just a month or six weeks after the district hired someone because they start and leave so quickly, says Derek Cooley, the district’s special education director.

“We used to have staff that would spend their whole careers in special education” at Godwin Heights, Cooley says. “We just don’t see that anymore.”

People often enter the special education field because they have family members with disabilities, or they come from a family of public educators, says Cooley. Throughout his own hiring history and over 20-year education career, he’s noticed this pattern, he says.

But what keeps special educators in schools “isn’t just passion,” Cooley says. “It’s also having strong mentoring and coaching, a manageable workload, and practical supports like tuition reimbursement that make the job sustainable and rewarding.”

Godwin Heights Public Schools is not alone in the struggle to recruit and retain special education staff. In fact, this field is typically cited as one of the top staffing problem areas among districts nationwide. During the 2024-25 school year, 45 states reported teacher shortages in special education, according to the Learning Policy Institute.

45

The number of states that reported teacher shortages in special education during the 2024-25 school year.

Source: Learning Policy Institute

These shortages can also lead to costly litigation between districts and families for missed special education services. To fill special educator vacancies, schools often rely on teachers not certified in special education or hire outside contractors to fill these roles.

These widespread shortages — which researchers and special education experts say were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic — continue to be a sticking point as the education community celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. The historic legislation, signed into law on Nov. 29, 1975, guaranteed students with disabilities the right to a free and appropriate public education nationwide. Until then, there was no federal requirement that schools must educate students with disabilities.

But five decades later, special education experts and advocates say much work remains to ensure that all students with disabilities indeed have access to a high-quality education.

Since the 1990s, special education has been the top staffing shortage area in U.S. schools, said Bellwether Education Partners in a 2019 data analysis.

Meanwhile, the number of students with disabilities ages 3-21 served by IDEA has surged by nearly 20% since 2000-01, to 7.5 million students in the 2022-23 school year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Derek Cooley is special education director at Godwin Heights Public Schools in Wyoming, Mich.

Permission granted by Derek Cooley

While all students are falling behind academically since the pandemic, as measured by the Nation’s Report Card and other data collections, students with disabilities are performing even worse than their general education peers. A majority — 72% — of 4th graders with disabilities scored below basic in reading, and 53% scored below basic in math on the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress. That’s compared to the 34% of 4th grade students without disabilities who scored below basic in reading, and the 19% who scored below basic in math.

Research and special education experts agree that special educator turnover and student outcomes are inextricably tied. A study released in May by the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research, for instance, found that in Washington state, high turnover among special educators is “especially detrimental to students with disabilities” and their academic performance.

“I think we’re far from the vision” and commitments of IDEA, says Heather Peske, president of the nonprofit National Council on Teacher Quality. As the latest scores from the Nation’s Report Card reveal, “there is the need for access to effective teachers, and so states and districts really need to focus on the opportunities available to them to increase both the quantity and the quality of special ed teachers,” Peske says.

But hope remains alive — and is actively fueling efforts by researchers and state education leaders to implement innovative strategies to address the widespread, decades-long struggle to staff special education.

When we fail to fully staff our classrooms, we fail to deliver on the promise of a free and appropriate public education for students with disabilities.

Abby Cypher

Executive director of the Michigan Association of Administrators of Special Education

In late September, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights released a report acknowledging that the special education teacher shortage is more than a staffing problem — it’s also a civil rights issue.

“I 100% agree with that,” says Abby Cypher, executive director of the Michigan Association of Administrators of Special Education. “When we fail to fully staff our classrooms, we fail to deliver on the promise of a free and appropriate public education for students with disabilities.”

Viewing the special education shortage as a civil rights issue is what keeps pushing Cypher to improve special educator recruitment and retention in Michigan. And it also reminds her that this is a problem that needs urgent solutions.

In recent years, Cypher says, the Michigan association has implemented new strategies to tackle the shortages as recommended by a state Legislature task force known as OPTIMISE, or Opening the Pipeline of Talent into Michigan’s Special Education. While the work is only just beginning, early results are promising, she said.

Special educators commonly leave the profession for a myriad of reasons, including low pay, poor working conditions, large workloads and heavy paperwork, as well as lack of school leadership support and professional development, according to special education experts.

With IDEA’s 50th anniversary upon us, K-12 Dive spoke with special education leaders and researchers about promising innovations to tackle special education teacher shortages and best practices for implementing the ideas at state and local levels.

Special educator shortages persist as a top staffing issue

The percentage of surveyed public schools that anticipated a need to fill certain teaching positions by subject areas before the start of the next school year.

Targeted compensation

Eighteen states differentiate compensation for special education teachers by paying them more than general education teachers. But Hawaii is the only one that offers over $5,000 in additional annual pay — the amount that research suggests could make a meaningful impact, according to a September NCTQ report.

The Hawaii Department of Education found in an October study that its $10,000 differential pay for special education teachers boosted teacher retention. But lower amounts had no impact on recruitment or retention in that state, the department said. The state’s average annual salary for all teachers is $78,124.

Increasing compensation or creating student loan forgiveness opportunities for special educators could boost both recruitment and retention, says Laurie VanderPloeg, associate executive director for professional affairs at the Council for Exceptional Children. “People are going to stay if they feel that they are being compensated for their workload and the time and the effort that they’re putting in.”

One way districts could cover higher salaries for special educators would be to stop paying teachers more across the board for having a master’s degree, Peske says. “We found that 90% of large school districts across the U.S. pay teachers more for having a master’s degree, and nearly one-third of states require districts to pay for these master’s degrees despite the evidence that master’s degree premiums are bad policy for almost everyone.”

In NCTQ’s own research, the nonprofit has found that master’s degrees for teachers do not correlate with effectiveness in the classroom, Peske said.

If we don’t have a strong climate and culture within the building, if we don’t have the administrative support, if we don’t have other areas to incentivize staff … they’re not going to stay.

Laurie VanderPloeg

Associate executive director for professional affairs at the Council for Exceptional Children

Meanwhile in Michigan, several educator unions have been able to negotiate higher wages for paraprofessionals who complete training developed by MAASE, Cypher says.

But VanderPloeg emphasizes that higher compensation is just “one piece of the puzzle.”

“If we don’t have a strong climate and culture within the building, if we don’t have the administrative support, if we don’t have other areas to incentivize staff … they’re not going to stay,” says VanderPloeg, who served as director of the federal Office of Special Education Programs during the first Trump administration.

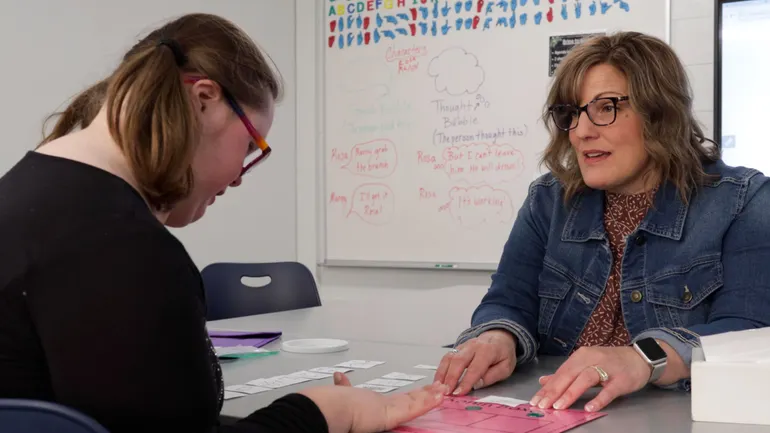

Tammy French, autism special education teacher at Bishop Elementary School in Rochester, Minn., goes over a new educational tool with autism paraprofessional Marion Fosdick after class on March 14, 2019.

Ken Klotzbach/The Rochester Post-Bulletin via AP

Training and professional development

In Michigan, Cypher says schools face a lot of turnover among paraprofessionals who often say in exit interviews that they left because they had neither the skills nor access to the training they needed to be successful. Paraprofessionals don’t need teaching licenses, and they typically are paid significantly less than full-time licensed teachers. These staffers perform various roles, such as assisting teachers in their classrooms through tutoring, helping to manage student behaviors or organizing instructional materials.

To address the paraprofessional turnover challenge and hopefully improve paraeducator retention, Cypher says that MAASE developed paraeducator standards with CEC. Since March, the Michigan association has trained nearly 5,000 paraeducators through this new professional development program, she says.

Special education administrators in schools don’t always have the capacity to provide high-quality professional development for their paraprofessionals, Cypher says. The new training empowers those administrators, including instructing them separately on how to effectively and consistently train staff across their districts.

But targeted training needs to go beyond paraprofessionals and special education administrators.

Prospective special education teachers, during their clinical training, should work with mentor teachers who are certified in special education, Peske says. This strategy has been proven to boost a new teacher’s efficacy in the classroom later on, she adds.

School principals also need more training in special education, according to industry experts and leaders. That is especially true given that special education teachers often cite a lack of support from their building administrators as a factor for leaving, says Natasha Veale, a special education leadership consultant.

States should require principal preparation programs to include more content and instruction on special education, Veale says.

And districts should provide principals with professional and personal development opportunities to help foster relationships with their special education teachers, she says.

Veale expresses optimism about the future of special education staffing given the increasing conversations at education conferences she’s seen about integrating a deeper understanding of special education issues more into school leadership.

Michigan is looking to tackle the leadership challenge through a new 18-month program called Developing Inclusive Leaders. This initiative, also from the Michigan Association of Administrators of Special Education, trains principals and building administrators on special education law, inclusive practices and collaboration with educators, families and communities.

A year into the program, Cypher said the association is already starting to see meaningful gains in school leaders’ knowledge of and confidence with overseeing school inclusion practices.

Developing pipelines

In recent years, grow-your-own programs have gained steam as an innovative approach for recruiting and retaining teachers across all instructional areas.

While these programs vary by district and state, they typically focus on bringing high school students into the education field or moving paraprofessionals into fully professional positions. Such initiatives can offer college tuition assistance to prospective teachers as they gain classroom experience working alongside veteran teachers — with the ultimate goal of earning a teaching degree or certification.

Illinois alone has 15,000 paraprofessionals with a bachelor’s degree, says Daniel Maggin, associate dean of research and professor in special education at the University of Illinois Chicago. If the state trained all those paraprofessionals as special education teachers, he said, its special educator shortage would be solved and there would even be a surplus.

That’s because paraprofessionals represent the group with the most accessible and fastest on-ramp for getting a special education license and endorsement, Maggin says.

Those professionals are local and they’re right there, and they’re familiar with students in the area, and it just makes more sense to capitalize on that population.

Natasha Veale

Special education leadership consultant

While that gives Maggin hope about addressing Illinois’ special education teacher shortage, he says it’s still unclear how the state could train that many people — and where the money would come from to do so. Such an effort would require district, state and federal support, he says.

Veale says most paraprofessionals have a strong desire to teach in special education full time, so grow-your-own programs for these staffers can be “a great way” to help alleviate the shortage.

“Those professionals are local and they’re right there, and they’re familiar with students in the area, and it just makes more sense to capitalize on that population,” Veale says.

Districts and states are indeed using the model to build up the special educator pipeline.

In 2024, Arizona launched two grow-your-own programs for special educators. One program offers tuition reimbursement to school districts for general education teachers who want to move into special education. Another Arizona program provides tuition reimbursement to school districts helping paraprofessionals earn a teaching certificate in the field.

And two years before that, North Dakota invested in an online grow-your-own program that trains paraprofessionals in rural areas to become licensed full-time special education teachers.

A group of high school students from Charlevoix-Emmet Intermediate School District in Michigan participate in a paraprofessional boot camp together in April 2025.

Permission granted by Michigan Association of Administrators of Special Education

In Michigan, grow-your-own programs often focus on training paraprofessionals for full-time and licensed teaching roles, according to Cypher. But without a pipeline to backfill their roles, that can lead to a deficit in paraprofessionals, she says.

To address that gap, Cypher says, the Michigan Association of Administrators of Special Education worked with the state education department to help high schoolers participate in a similar grow-your-own program, known as a paraprofessional boot camp, that started in March 2025.

The boot camp is offered as a career and technical education course where high school students train and work in elementary schools for several hours in a day. Then after graduating high school, they can immediately step into a paraprofessional role.

This new initiative not only helps fill paraprofessional positions but could lead to more interest in full-time special educator roles, Cypher says. “Once students have access to those standards on being a paraeducator, it might entice them to consider going into teaching as well.”

News Graphics Developer Julia Himmel contributed data and graphics support to this story.