Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

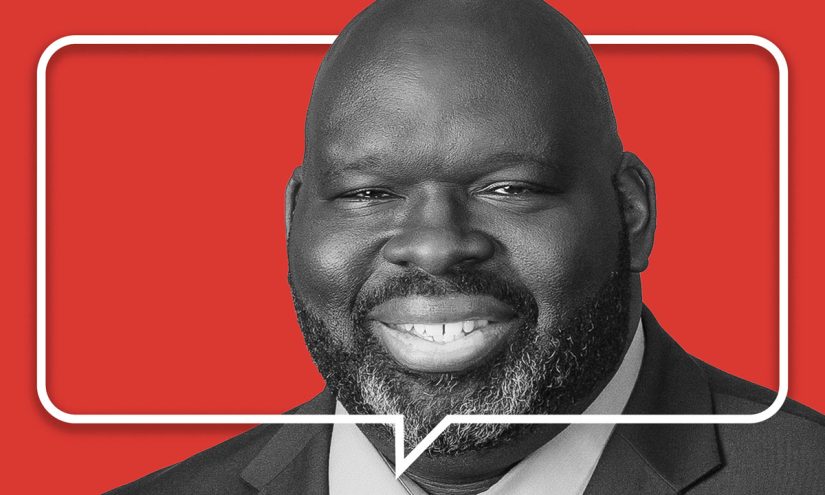

Roosevelt Nivens didn’t set out to become a school superintendent. He wanted to be a football coach. But his innovative, student-first mindset in running Lamar Consolidated Independent School District in Texas led to his recognition Thursday as the nation’s top superintendent.

Nivens’ commitment to leadership, communication, professionalism and community involvement helped him achieve the Superintendent of the Year Award on Thursday at The School Superintendent Association’s national conference in Nashville.

The organization selected Nivens from three other finalists in Maine, Kentucky and Maryland. He’s led a district of nearly 50,000 students west of Houston since 2021, part of his 30 years of education experience that began with teacher and principal roles in Dallas.

“If you’re smart, you realize you don’t get here by yourself,” he said. “It’s a lot of people — 49,000 kids back home, 6,500 staff are working right now doing a phenomenal job. But it’s a tremendous honor.”

Nivens spoke with The 74’s Lauren Wagner on Friday at the conference. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What initiatives and developments are you most proud of during your tenure at Lamar Consolidated?

We are opening an in-district charter school for kids with autism spectrum disorder. The traditional setting works for some, but not for all. So what can we do to support a group of students who want that support? I sat with a parent back in November, and they were paying $40,000 a year to get their child support outside of school. So we want to try to support kids and families. That’s our purpose. It’s opening in August, but we’ve been planning this for two years.

I would also say we’ve increased the number of students who are thinking about post-secondary [plans]. I secured private funding for a college superintendent trip. So I take two juniors from every high school — 14 kids who are first-time college goers — and I take them out of state. It’s fully funded by private donors. Those kids haven’t even been out of the county. We’ve done it three years in a row now. The first year was Louisiana, last year was Arizona and then North Carolina.

We’re opening a brand new career technical education center in August. Lamar didn’t have a CTE center when I got there — we were partnering with different colleges. I don’t believe kids should have to decide what they’re going to do so early. The system is built where you have to say, ‘Okay, child, you have to choose advanced academics or advanced band or athletics. Pick and choose.’ Give them options. You know, they’re 14 years old. We wanted to make sure everybody had options on what they wanted to do.

Your district has rapidly grown since you started your role in 2021. What challenges have you dealt with to keep up?

We’ve added about 14,000 kids. There are 49,000 now and when I got there, there were around 36,000. I’ve opened 15 schools in five years, and that takes planning. My chief operations officer and his team do a great job helping me and bringing me data, and we think about where schools would go and when they need to go.

Another challenge is that since we’re growing so fast, we have to rezone schools. We’ve had a lot of resistance from parents. Finally, I publicly intervened, because we may take students out of one historic school and put them in a brand new campus, and parents are like, ‘No, I went to that school.’ But that’s not fair. I was like, ‘Just because you went there 50 years ago doesn’t mean these kids should still be in that school.’ Our first bond issue in 2022 was $1.5 billion, and the one in 2025 was $1.9 billion. And the community supported it.

What’s your favorite part about your job?

Definitely campus visits. I love listening to our babies. I taught elementary school and didn’t like it because they were too small — I was a high school guy. But now when I have a tough day, I go to a campus and go see some pre-K babies, some kindergarten babies. They’re the sweetest. And they don’t judge anything. One kid was like, ‘You’re as big as a truck!’ And I said, ‘That’s the laugh I needed today, man.’ By far, that’s my best part of my job.

Did you want to become a superintendent when you first began teaching?

No. I didn’t want to. I wanted to be a head football coach. That was it. I worked with a lot of great people, but I worked with a few who were not good with kids. I would have my [students] call me and say, ‘Coach, I don’t have a ride.’ Or, you know, ‘My mama’s high.’ All kinds of stuff. And I would go pick them up or whatever I needed to do. After school, I would take them home, and I would buy them food. And I didn’t see [some teachers] doing that. And I was like, ‘Why are you in this job if you’re not doing that?’ They always would talk bad about the job and I was like, ‘Do you hate kids?’ So I would go home and talk to my wife about it, and she would say, ‘What are you going to do about it?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m their peer. I can’t do anything about it.’ She said, ‘Yeah, you can. Become a principal.’

So as a principal, I did all the hiring, and if you didn’t know how to teach math, that was fine. If you’re a good person and you love kids, we could teach you how to teach math, right? Then I started working with other principals who I thought weren’t doing as much as they could for their campuses. So it was kind of the same mindset — you know what, I’ll become a superintendent.

What keeps you up at night right now as a superintendent?

In general it’s the contrast between COVID and now. When COVID hit, all the parents had to teach their own kids and their teachers were heroes, right? Now it’s like the world has forgotten that, and the reverence for the job and for the profession is gone. You know, give teachers an opportunity. It’s an automatic, ‘My son said this.’ And, ‘Why did you do that? I’m going to get you fired.’ It’s a cancel culture. So I talk a lot in my community about grace. We’re all human. The teacher might have done something wrong, and I’m not saying we’re always right, but let’s have a conversation about it. I don’t think anybody has bad intentions, right? But let’s have some grace with each other. Let’s be more kind to each other.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how