There’s a comforting belief running through higher education that goes something like this.

If we listen to students, really listen, then our decisions become legitimate.

That consultation itself confers credibility, and that student voice, once invited and recorded, has done its job.

It’s an understandable belief, but it’s also one of the most quietly damaging myths in modern higher education.

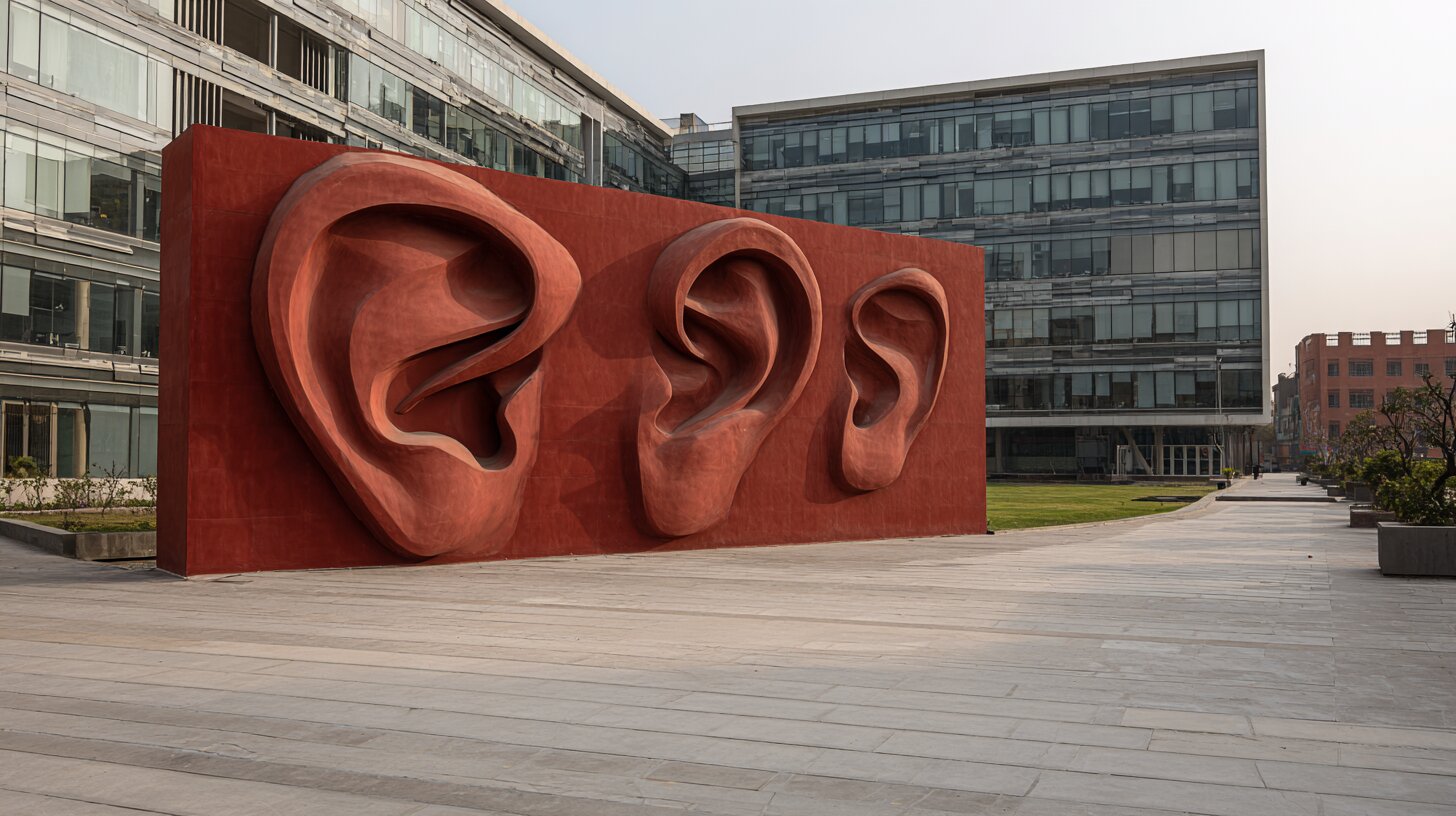

Call it the listening–legitimacy fallacy – the assumption that consultation itself produces legitimacy, even when it doesn’t change outcomes.

Because universities aren’t struggling to hear students any more – they’re struggling to be changed by them and be shaped by them.

Hearing without acting

By any reasonable measure, most universities and SUs have become exceptionally good at “hearing” students. They survey, repeatedly. They consult, formally and informally.

They run focus groups, build dashboards and heat maps, appoint student panels and advisory groups, and publish glossy frameworks about engagement, partnership, and co-creation.

In Ireland specifically, this work isn’t accidental or peripheral – it’s systematised. National programmes explicitly promote student engagement in decision-making, partnership frameworks sit alongside quality assurance processes and governance codes, and student voice is referenced across strategic plans and institutional narratives.

The relaunch of national listening tools this year like the Student Survey sits within the same trajectory – a sector signalling, again, that student perspectives matter, that we want better data, clearer insight, stronger feedback.

All of this is, in principle, positive and necessary. But none of it answers the question students are actually asking.

What students actually see

When we move away from frameworks and into what students experience day to day, a different narrative emerges – one that’s remarkably consistent across institutions, disciplines, and levels of study. Students say things like:

They ask us questions they’ve already answered.

They want our stories, not our authority.

We’re included, but only once the shape of the decision is already set.

This isn’t cynicism – it’s pattern recognition. Students aren’t rejecting engagement, they’re diagnosing its limits, and this is where the uncomfortable pivot lies. Student voice without consequence isn’t empowerment – it’s extraction.

When students are asked to contribute time, emotional labour, credibility, and personal experience – often while juggling work, caring responsibilities, and financial pressure – yet see no meaningful shift in outcomes, participation stops feeling like partnership and starts feeling transactional and tokenistic.

Listening as substitute

The problem isn’t that universities ask students for input – the problem is what that input is allowed to do.

Too often, student voice is invited into processes that are already constrained or predetermined by timelines, budgets, risk tolerance, regulatory expectations, or institutional habit. Students are asked to comment, refine, reflect, and react – rarely are they asked to decide, or to shape decisions before the options have been scoped.

Listening becomes a performance of openness rather than a mechanism of accountability, and consultation becomes a buffer between leadership and consequence. Students notice.

This is how symbolic listening takes root – extensive engagement activity with minimal decision impact.

Symbolic vs operational

The distinction matters, because legitimacy doesn’t emerge from participation alone – it emerges from consequence.

Most universities, SUs, and higher education institutions have invested capacity, resources, and finances heavily in symbolic listening. Very few design for operational legitimacy.

This moment in higher education is defined by complexity – cost-of-living pressures, commuter campuses, hybrid learning, diverse student populations, and declining trust in institutions more broadly.

In that context, legitimacy isn’t symbolic – it’s operational. Students aren’t just moral stakeholders, they’re co-producers of the academic environment, and their behaviours – engagement, persistence, withdrawal, advocacy, resistance – actively shape institutional outcomes. When students believe their participation has no meaningful effect, two things happen.

First, institutions lose their most capable student leaders, who migrate elsewhere – to campaigns, social media, external pressure, or disengagement – because that’s where change feels possible. Second, institutions lose access to their most valuable intelligence – not opinion, but insight grounded in students’ own realities. Listening without consequence doesn’t just fail students – it weakens institutions. This isn’t just a student engagement issue, it’s a governance risk.

The translation problem

Most universities have built strong front ends of engagement – collection, consultation, representation. What they haven’t built with the same care is the back end – the machinery that translates voice into decisions, decisions into action, and action into visible change.

This isn’t primarily a cultural failure – it’s a design failure. Student voice tends to break at precisely the point where power enters the conversation, where trade-offs must be made, resources allocated, risk owned, and priorities set.

At that point, student input is too often reframed as insight rather than authority, evidence rather than mandate – and so the system continues to listen, while remaining unchanged at its core.

There’s a simple way to assess whether student voice has real legitimacy within an institution or organisation. Ask:

- If student voice disappeared tomorrow, which decisions would materially worsen?

- Where would risk increase?

- What blind spots would grow?

- What outcomes would deteriorate?

If the honest answer is “none,” student voice is very likely symbolic rather than operational.

Goodwill isn’t enough

Much of the discourse around student partnership still leans heavily on relationships – trust, openness, shared values, mutual respect. These matter, but they aren’t sufficient on their own.

Systems that rely on goodwill rather than structure are fragile – they work when personalities align and workloads allow, and they fail silently when conditions change.

The strongest models of student influence don’t depend on sentiment, they embed power structurally and culturally through decision rights, formal roles, clear remits, and transparent accountability. Where student influence is strongest, it’s least dependent on who happens to be in the room.

If institutions want to move beyond the listening–legitimacy fallacy, three shifts are required.

From consultation to consequence. Institutions must be explicit about where student input can and does change outcomes. Ambiguity breeds mistrust, and clarity builds credibility – even when the answer is no.

From participation to power. Not every decision can be co-decided, but some must be. Naming where students have real authority is more honest than pretending everything is a partnership – and where it’s named, it must be true, authentic partnership, even if that makes some of us uncomfortable at times.

From performance to accountability. Students don’t need perfection – they need evidence that the system is honest and accountable. “You said, we did, we couldn’t – and here’s why” should be a governance norm, not a communications exercise we launch every time we want participation in a survey or focus group.

None of this is radical – it’s simply rigorous.

Beyond the myth

Renewed attention to partnership frameworks, listening tools, and student engagement reflects a sector – or most of a sector – that genuinely wants to get this right. Across institutions, there’s clear evidence of investment, intention, and care, of people trying to build better feedback loops, stronger relationships, and more inclusive decision-making processes. That matters, and should be acknowledged.

But legitimacy isn’t produced by listening alone, no matter how sophisticated the tools or how well-intentioned the process and people. Listening creates the possibility of legitimacy – it doesn’t complete it.

Legitimacy is produced by consequence – by the visible, traceable impact of student voice on decisions that shape academic life. It’s produced when students can point to moments where their participation altered an outcome, shifted a priority, or changed the direction of travel, even when that change was partial, difficult, or contested.

Student voice becomes credible only at the point where it can change something real – not every decision, and not always decisively, but meaningfully, and in ways that can be seen, explained, and accounted for.

Because voice that doesn’t alter power eventually alters participation instead. Students adjust what engagement is worth, who it’s for, and whether it’s worth sustaining. Over time, perception shifts – partnership begins to look performative, consultation begins to feel extractive, and silence becomes a rational response rather than a failure of interest.

And by the time institutions notice that silence – when participation drops, trust erodes, or legitimacy is openly questioned – it’s already too late to recover what was lost quietly along the way.