1. India set to become the world’s largest higher education system by 2047

Delegates at The PIE Live India 2025 heard how India’s projected eightfold growth into a $30 trillion economy presents vast opportunities for higher education, with Niti Aayog’s Shashank Shah asking attendees, “If not India, then where?”. Speakers also highlighted that India is on track to become the world’s largest higher education system by 2035, with over 90 million students — positioning transnational education as a key growth driver.

2. Outbound Indian university enrolments fall after three-year rise

For the first time in three years, Indian students pursuing higher education saw a drop of around 5.7%, with over 1.25 million studying at international universities and tertiary institutions, compared to 1.33 million in 2024. This comes amid a range of policy changes in major destinations and the rise of cheaper, nearer options for students.

The decline is also reflected in growing financial uncertainty around studying abroad in India, with remittances for overseas education falling to their lowest level in eight years when comparing April – August 2025 figures.

3. More Australian and UK universities set sights on campuses in India

In July 2025, four universities from the UK and Australia — La Trobe University, Victoria University, Western Sydney University, and the University of Bristol — received Letters of Intent (LoIs) to establish branch campuses in India, just a month after the University Grants Commission (UGC) issued LOIs to five other universities from the UK, US, Australia, and Italy. Currently, nine UK and seven Australian universities have either opened campuses or are in the process of doing so, with not only GIFT City but other economic hubs such as Noida, Bengaluru, Mumbai, Gurugram, and Chennai also hosting campuses.

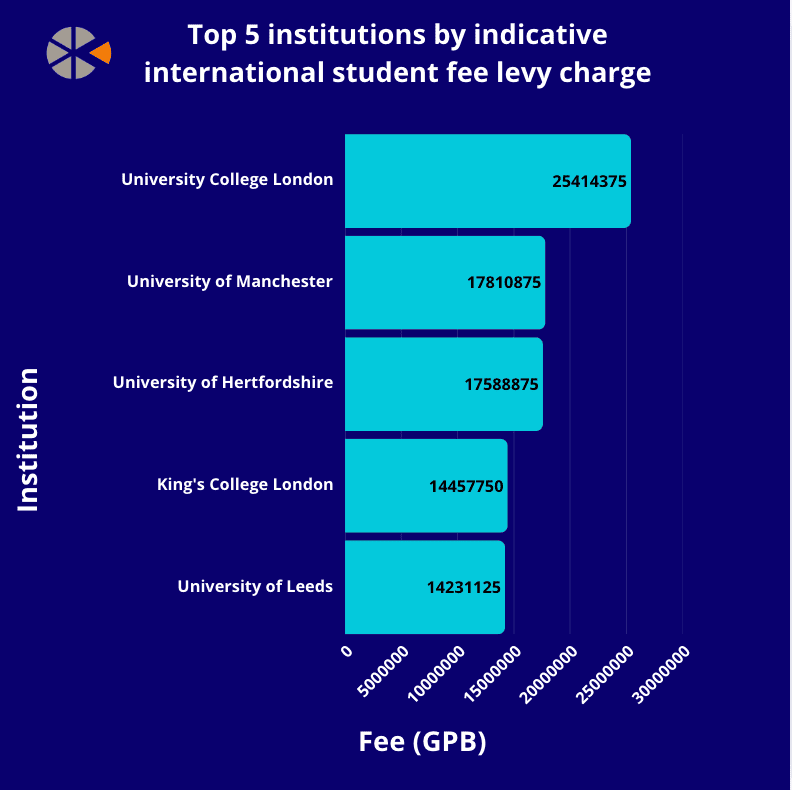

Despite this growth, The PIE has explored the rising debate around the “rush” to enter India’s higher education space at a time when international universities are cutting back on jobs and research, particularly in the UK, where four in ten English universities are believed to be in financial deficit, according to the Office for Students (OfS).

4. Southampton opens India operations, attracts applications from Middle East and South Asia

The University of Southampton, the UK’s first branch campus in India, told The PIE at The PIE Live India 2025 in January that the process of establishing its Delhi campus had been “fast, frenetic [and] exciting” from start to finish.

The India campus, which began operations in August 2025, has since gained strong traction, receiving over 800 applications, with around 200 students joining the first cohort, and applications also coming from the UAE, Nepal, and Myanmar.

5. Sri Lanka set to welcome first ever UK university campus

The South Asian island nation, which is the second-largest host of UK TNE students, saw its first-ever UK university branch campus this year, with the University of West London launching a dedicated facility in the capital, Colombo, for local students.

Meanwhile, Charles Sturt University is set to become the third Australian university to establish a campus in Sri Lanka. The country’s skills gaps and its Vision 2048 development agenda are driving Sri Lanka to pursue such opportunities, as it continues to face limited capacity across its 20 public universities, despite around 160,000 students seeking tertiary education each year.

6. Trump and Modi pledge stronger India–US higher education ties

While US President Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi appear at odds on trade, with Trump doubling tariffs on India to as much as 50%, both leaders are advocating closer ties in higher education. Their focus includes scientific research, dual degrees, joint centres of excellence, and offshore campuses, with Illinois Tech becoming the first US institution to receive approval for a campus in India.

7. Cities within cities to host international university campuses

Major Indian cities are planning dedicated education hubs on the outskirts of newly developing urban areas. While “Third Mumbai”, a purpose-built education city, is set to host five international universities near the upcoming Navi Mumbai International Airport, the Tamil Nadu Industrial Development Corporation (TIDCO) is developing the Knowledge City in Tiruvallur.

The Tamil Nadu Knowledge City aims to create a first-of-its-kind education and research hub in southern India, attracting both international and domestic universities, along with academic institutions and research organisations.

8. Bangladeshi government opens doors to international campuses and dual programs

Bangladesh’s University Grants Commission (UGC) has announced its plans to develop “clear and stringent” guidelines for formulating a policy around international university branches in the country. While there has been interest from countries like the UK and Malaysia, the policy’s review and national interest assessments are currently underway.

The establishment of branch campuses would be seen as key, as Bangladeshi students have faced increasing visa denials and allegations of misusing study visa status to enter the labour market, with universities in the UK and countries like Denmark imposing restrictions on them.

9. F‑1 visa declines hit India and China hardest

Though India has retained its position as the US’s largest sending country, accounting for 31% of all international students according to 2024/25 data, it — along with China — has borne the brunt of declining US study visa issuances. The number of Indian students receiving US study visas fell by over 41% in the year to May 2025, amid a range of policies targeting international students, including heightened social media vetting, proposed visa time limits, and increased deportations and SEVIS status terminations over political views and other minor misdemeanours.

These developments have made international students, particularly Indians, more cautious about studying in what is widely considered the world’s top study destination.

10. India to unveil new scheme for Indian-origin researchers overseas

India’s Ministry of Education, the Department of Science and Technology (DST), and the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) are working to “bring back” Indian-origin researchers and scientists with strong academic credentials, targeting 12–14 priority STEM areas deemed strategically important for national capacity building.

11. UGC launches dedicated portal for study-abroad returnees in India

In April 2025, the UGC launched a standardised framework for recognising international degrees in India. Indian students who have studied abroad and wish to return for further education or employment can now apply for an equivalence certificate through the higher education body’s portal by paying the prescribed fee.

12. B2B international education platform Crizac debuts on Indian stock market

Kolkata-headquartered Crizac, which plans to expand beyond student recruitment into areas such as student loans, housing, and other services, and is targeting new geographies and growth markets within India, raised £74 million in its Initial Public Offering (IPO).

The company listed on the National Stock Exchange (NSE) and Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), becoming one of the few education platforms to enter the IPO space. Major edtech players like PhysicsWallah followed later, aiming for a USD$3.6 billion valuation through a USD$393 million IPO.

13. Cost drives Pakistan’s TNE growth as student mobility barriers rise

International universities and education providers are pivoting to TNE in Pakistan due to the country’s price-sensitive environment which is creating challenges for students going abroad for education. While Pakistan faces weak investment in research and development, its strategic growth vision is driving rising demand for international qualifications among students, delegates heard at The PIE Live Europe 2025.

This shift is particularly significant as several institutions, especially from the UK, have halted recruitment in certain cities and increased deposit requirements from 50% to the full tuition fee.

14. International universities tap into Nepal’s mobile student population

With a student mobility ratio of 19% — ten times that of its giant neighbours, India and China — Nepal has attracted visits from over 16 universities under the Nepal Rising initiative. The country is already planning 30 or more franchise TNE campuses, with 30,000 students approved by the Ministry of Education.