It’s hard to learn if you’re ill – good health is one of the classic prerequisites to learning.

But one of the most frustrating things about the debate around student health in the UK is that there isn’t one.

Anecdotally, poor access to preventative healthcare and health services tends to be justified either by NHS pressure from an ageing population or by expectations that universities should do more with less.

Both arguments have merit, but they leave the crucial link between health and academic success stuck in that Spiderman meme, while the public and the press blames students for “boozing it up” or “inventing ADHD.”

Mental health is well, almost over-researched – but health concerns for students go far beyond the usual talking points. Gonorrhoea diagnoses are at record levels, with the UK Health Security Agency identifying students as a key factor, drugs are the subject of many a survey, disordered eating among students is largely ignored, and sleep deprivation seems to be an issue. Some surveys say dental issues are increasingly common – as one expert notes, “dental health is mental health.”

The question is whether any of these issues are unique to students – and to the extent to which they are, what sorts of policy interventions might address them.

In the latest wave of Belong, our polling partnership with Cibyl (which our subscriber SUs can take part in for free), we examined everything from general health perceptions and healthcare access to specific areas like sleep quality, alcohol consumption, sexual health confidence, and experiences with the NHS.

The results come from our early 2025 wave, with responses from 1,055 students across 88 providers. The data has been weighted for gender and qualification type (undergraduate, postgraduate taught, and postgraduate research) to ensure representativeness. There’s also analysis of various free-text questions to illustrate what’s going underneath the headline results.

Yeah, I’m OK

First of all, we asked students a standard question used in national surveys asking them to rate their own health. Only 20 per cent of students rate their health as “very good” compared to 48 per cent of the general population.

![]()

Combined figures show that while 61 per cent of students report “good” or “very good” health (compared to 82 per cent in the general population), a full 32 per cent describe their health as merely “fair” – nearly two and a half times the rate in the general population.

Qualitative comments illuminate what lies beneath. Many students clearly differentiate between their physical and mental wellbeing:

My physical health is generally good, whereas I have faced some struggles in mental health (which can also at times impact my physical health).

Physical is usually good but sometimes a little bit hungry after trying to save some food for other days. Mentally I am ok but I don’t fill very fulfilled.

My physical health is immaculate however my mental health is the worst it’s ever been.

Several respondents directly connected their health status to the pressures of university life:

Could be better, I’m finding learning incredibly stressful as part of a full-time job.

Almost died from an overdose of caffeine trying to work on a essay and had two breakdowns.

Feel very tired due to uni, aware my health could be better, but do not have the time.

For others, university has provided structure and support:

Being at uni has helped me focus more on my self care and mental health to improve

My health is generally good because I prioritise self-care, balance my studies, part-time work, and rest, and use available support when needed.

Many respondents described their health as variable and requiring ongoing management:

I am physically keeping fit, mental health I am working on, some days are better than others.

My everyday health is a constant battle that I have to take a multitude of medications. I have good days and bad days and am lucky if I get a decent amount of sleep.

Everyone gets their bad days and good.

A significant number of students also reported living with chronic physical health conditions or disabilities:

I’m disabled. I always feel bad.

I am a full time wheelchair user with ME and fibromyalgia, so I am in a lot of pain and fatigue.

I had a diagnosis of a rare cancer called Leiomyosarcoma in 2023. The cancer has gone but it’s left me with a whole range of health problems.

Overall, the narrative accounts reveal complexity – where mental and physical wellbeing are often experienced differently, academic pressures can both harm and support health, daily fluctuations in health status are common, and chronic conditions create persistent challenges that require constant navigation of university life.

Correlations or causations?

We wanted to know if there are relationships between health and key elements of student experience. The data shows strong correlations between student health perceptions and their sense of belonging – among students reporting “very good” or “good” health, 85 per cent feel part of a community, compared to just 68 per cent among those reporting “bad” or “very bad” health:

![]()

This pattern extends to whether students feel free to speak – 93 per cent of those with better health feel free to express themselves, compared to only 77 per cent of those reporting poorer health conditions:

![]()

On teaching quality, 91 per cent of students with “very good” or “good” health report positive teaching quality, while 84 per cent of students with “fair,” “bad,” or “very bad” health still rate teaching quality positively:

![]()

Correlation is not causation – though it’s technically possible that poor teaching or poor belonging is making students ill, to the extent that the free text offers clues, it suggests that the causation is the other way around – poor health appears to be robbing students of the ability to take advantage of the academic and social opportunities on offer.

Are you registered?

The good news in our polling is that most students (93 per cent) are registered with a GP. The problem is that only 65 per cent are registered near their place of study. A quarter (25 per cent) remain registered elsewhere in the UK, while five per cent maintain registration in another country:

![]()

The qualitative comments reveal several distinct reasons for not registering locally. Many students commute to university and maintain their home GP registration:

Because I don’t live at uni. I commute. So it would make sense to have my GP in my home town

As I do not live on campus, it is easier for me to stay registered with my GP, who is closer to home.

Even students who do live at university often cite proximity to home as a reason not to change registration:

It’s only an hour to my home town so easier just to stick with them.

Don’t feel I live far enough away from home to register with another GP.

Continuity of care emerges as another significant concern:

If I sign up for a local GP here, I would be de-registered from my home GP. Since I prefer to stay with my home GP for continuity of care and I only need healthcare support when I’m at home, I haven’t registered with a GP at uni.

Because I am waiting for talking therapies which I can only get if I am registered with a GP in Somerset so registering in Plymouth will take me off of the waiting list.

I have been on a waiting list for migraine treatments in my home town and don’t want to start again and wait even longer.

Home GP knows about my disabilities and there back history.

And some students express concerns about quality of care:

They are useless.

I’ve heard some horror stories about the GP here, and when my friend was too sick to eat or sleep, they wouldn’t even talk to her.

Dental registration shows a more concerning pattern, with a third of students (33 per cent) reporting they are not registered with a dentist at all. Only 17 per cent are registered near their place of study, while 31 per cent maintain registration elsewhere in the UK and 12 per cent in another country:

![]()

Despite the low registration rate, 56 per cent report having had a dental check-up in the past 12 months – almost identical to rates found in the general population, although that’s hardly a corks-popping moment for the country.

Students cite NHS availability and cost as major barriers:

There is no NHS dentist available in the county!

There are no dentist mine is private.

NHS is underfunded so it’s impossible to access these services. Private dentists are unaffordable.

It is literally cheaper for me to travel to my country for a dentist appointment where there is healthcare than doing it here.

Many students also note that dental appointments can be scheduled during visits home:

Dental care is something that is tended to like every 6 months or so. So it makes sense to just keep the appointments whenever I am back home.

Only visit once every 6 months so can plan to go home when the appointment is approaching.

As with GP services, commuting students typically maintain their home dentist:

I commute rather than live on campus, so it was more convenient to stay with my dentist closer to where I live.

Loyalty to existing dentists also emerged as a significant factor:

I’m with an NHS dentist at home and I don’t want to lose my NHS dentist by moving to a different one as it’s difficult to find NHS dentists.

I go home enough to see my home dentist who has known me for 20 years.

Can’t get no

In early April, the long-running British Social Attitudes survey told us that public satisfaction with the NHS had hit a new low – just 21 per cent said they were satisfied with the NHS in 2024, with waiting times and staff shortages the biggest concerns.

So we wanted to know what students think. In our polling nearly half (49 per cent) reported being either “very dissatisfied” (12 per cent) or “quite dissatisfied” (37 per cent) with the NHS. In contrast, only 31 per cent expressed satisfaction, with a mere three per cent indicating they are “very satisfied”:

![]()

Many respondents expressed frustration with the difficulty of getting appointments and lengthy waiting times:

12 hours wait time at A&E is scandalous, people die waiting for ambulances, good luck getting an appointment.

It takes too long to get anything sorted.

I have waited long periods to have health checks and it has taken months to get in to see anyone.

Can’t seem to get a same day appointment.

A significant number attributed NHS problems to systemic underfunding:

It is underfunded, there is too much stress on all the services so they can’t take care of patients properly.

It’s massively underfunded and unsupported by the government. The Tories ripped it to shreds.

As an international student I pay £776 for this shit shower, joke of a country really is.

It isn’t the fault of the nurses, doctors hospital staff etc. It’s that the NHS is criminally underfunded.

Many highlighted specific concerns about mental health services:

You have to be attempting to kill yourself for the NHS to help you with mental health problems.

I’m diagnosed with anxiety and it’s been the worst mistake of my life I wish I just kept it between me and my therapist they don’t listen to a word I say.

The NHS cannot take the strain of the sheer number of mentally ill young people.

Mental health services and waiting times just to have initial appointments are terrible.

Respondents also expressed frustration with a lack of communication between different parts of the system:

Nobody talks to each other and waiting lists are long.

Lack of communication between hospitals, staff members within the same hospital.

Less continuity of staff – like you’re on a conveyor belt passed along looking at the surface issue – not the deeper.

Long waiting times and lack of communication between various departments. Over complicated administration processes.

And some had specific concerns about the quality of care they received:

When I went to an emergency dentist in the UK, they left something in my tooth that rotted and I had to have the tooth removed.

I’ve been to 4 different hospitals about my knee which keeps dislocating and popping. They don’t care to be honest.

A male consultant kept refusing to answer my questions before a medical procedure and complained when I refused to let him touch me.

I feel like I treat myself rather than being treated.

Drugs, alcohol and food

Plenty of press stories surround the idea that Gen Z is more likely to be clean living and teetotal than previous generations. Our polling suggests that 26 per cent of students never consume alcohol – a slightly higher abstention rate than the general adult population, where according to the latest NHS data 19 per cent report not drinking in the past year.

For those who do drink, consumption patterns are distributed across different frequencies:

![]()

This pattern suggests lower regular drinking among students compared to the general adult population, where 48 per cent report drinking at least once a week. When students do drink, most report moderate consumption (the below graph only includes those who indicated they drink):

![]()

It’s worth noting that 7 per cent of respondents chose not to answer the question about quantity consumed, which may indicate some hesitancy to report higher levels of consumption.

We also asked about drugs – specifically asking students about illegal drugs or prescription drug misuse within the past month. The results show that a small minority of students (seven per cent) reported using illegal drugs or misusing prescription medications in the past month, a rate much lower than is often perceived.

Back in 2023 we also carried out polling on disordered eating amongst students, having spotted some pilot polling that the ONS did on the issue the previous year. Little has changed.

In the ONS work, our 2023 poll and this wave, we used the SCOFF questionnaire – a validated screening tool for detecting potential eating disorders – to assess students’ relationships with food and body image. The results show concerning patterns:

![]()

- Nine per cent reported making themselves sick because they felt uncomfortably full

- 26 per cent worried they had lost control over how much they eat

- Eight per cent reported significant weight loss in a three-month period

- 19 per cent believed themselves to be fat when others said they were thin

- 19 per cent reported that food dominates their life

When these responses are analysed according to SCOFF scoring criteria:

- 49 per cent showed no sign of possible issues (compared to 50 per cent in the ONS national sample)

- 25 per cent demonstrated possible issues with food or body image (compared to 23 per cent in ONS)

- 24 per cent showed possible eating disorder patterns (compared to 27 per cent in ONS)

The findings suggest that the UK student population closely mirrors national trends in disordered eating and problematic relationships with food and body image. The particularly high percentage of students who worry about losing control over eating (26 per cent) and who perceive themselves as fat when others say they’re thin (19 per cent) – and the relationship we found between those issues and mental health in 2023 – suggest significant work to yet be done, that could have very positive impacts.

No snooze, you lose

Sleep and rest is a huge part of health. Our results show a mixed picture over quality and quantity. While 47 per cent of students report “very good” (10 per cent) or “fairly good” (37 per cent) sleep quality, nearly a quarter (24 per cent) describe their sleep as “fairly poor” (15 per cent) or “very poor” (nine per cent). More than a quarter (28 per cent) fall into the middle category of “neither good nor poor.”

![]()

When it comes to sleep duration, half of students (50 per cent) report getting six to seven hours of sleep per night on average, with an additional 26 per cent getting eight to nine hours. However, a concerning 21 per cent are sleeping fewer than six hours per night, with 20 per cent getting just four to five hours and one per cent less than four hours.

![]()

The findings show a potential improvement compared to the polling we carried out a year ago, which found students were getting just 5.4 hours of sleep per night on average. Our current data suggests a higher proportion of students are now achieving six-plus hours of sleep – but it’s still not nearly enough.

The 2024 exercise saw strong relationships between sleep duration and both life satisfaction and anxiety levels. Students getting 8-8.9 hours of sleep reported significantly higher life satisfaction scores (6.9 versus the average of 6.3) and lower anxiety scores (4.7 versus the average of 5.0) compared to those sleeping less.

Students in that survey clearly recognised the importance of sleep:

I need more sleep!

Could probably do with more sleep, just trying to get 8 hours a week would be nice.

But the qualitative data highlighted several factors affecting student sleep patterns:

- Academic pressures: “Currently, the workload is too big.”

- Employment demands: “Being in my overdraft monthly, long hours at work cuts into my sleep time.”

- Irregular timetables: “What would help? A more consistent timetable.”

Housing a problem

Governments love their public policy silos – but one of the things SUs wanted us to look at was the relationship between housing and health. In this data, nearly half of respondents (49 per cent) reported that housing does affect their health – with 27 per cent noting a positive impact and 22 per cent experiencing negative effects:

![]()

Many students reported health concerns related to poor physical conditions in their accommodation:

Student houses have mold and have usually been untouched from when they were bought 12 years prior. My house has plenty of mold which no doubt hasn’t helped things when I have been unwell.

I live in a very mouldy flat that I have to spray at least once a fortnight to tackle the mould. It is damp and mouldy, but the landlord just tells me to open a window.

My window doesn’t open and was reported to reception before I even arrived in September I have gone back to report it to them multiple times and they still haven’t done anything about it. I also do not have an extractor fan which works in my bathroom this means I have no airflow in my room.

Housing affordability emerged as a significant stressor affecting mental health:

Every year when my rent is rised it impacts my mental and physical health hugely as it causes me a lot of stress and forces me to cut things that make me feel better.

It’s Cornwall so the housing situation is abysmal… Landlords and estate agents take advantage of this to a disgusting degree and overcharge students to the point of spending all or the vast majority of your student loan just on rent.

After rent I have no money. Landlords know how much student loans we get and scalp accordingly.

The social environment created by housemates significantly influences mental wellbeing, with both positive and negative experiences reported:

My flatmates are incredibly unclean and disrespectful.

My housemates are rude and disrespect and leave a mess everywhere and they smoke weed despite me asking them to stop loads. It makes me not want to be at home.

Although on the positive side:

My housemates are lovely people to talk to and I get along with them really well.

I love my housemates, we cook and eat dinner together every day and it’s nice to just hang out.

Insecurity about housing arrangements creates significant stress:

I rent privately, so the expensive rent combined with low-quality housing and anxiety around the permanence of my home significantly affect my anxiety.

I recently had my housing group fall apart and will need to give my ESA up to a friend of my partner in Essex due to inability to find student housing that will allow me to keep her.

Landlord left us with no heating or hot water for 2 months.

And some students reported significant benefits from supportive housing environments:

It has been beneficial moving out of a toxic home environment. I have become very close with a few of my flatmates here.

I recently got my own place after being in a house where I was abused. It’s more difficult financially but at least I don’t have someone else hurting me on purpose.

I have found moving to a house away from campus with people I am close with has had a positive effect due to the home/uni balance I now have.

It’s another classic silo issue. The failure of any of the four governments to cobble up a student housing policy is a housing issue – but it’s also an educational issue and a health issue. And because it’s a student issue, it ends up being an issue that is not handled or planned as an issue by anyone. And so it just gets worse every year.

Not so free periods

We were also asked to look at menstruation and sexual health. On the former, the results suggest that most respondents find menstrual products reasonably accessible – save for an important minority:

![]()

When asked whether menstruation impacts their daily life, respondents were fairly evenly split:

![]()

The relatively even division suggests that menstruation-related challenges continue to affect a significant proportion of the student population, potentially influencing their academic performance, social engagement, and overall university experience.

Then on sexual confidence and health, the results show generally high levels of self-reported confidence:

![]()

The standout is that approximately 18 per cent lack confidence in accessing NHS sexual health services – the highest area of uncertainty among those surveyed.

The findings present an interesting contrast to a 2021 HEPI survey on sex and sexual health among students. That research found significant variations in consent understanding and confidence levels, particularly when examining school background and gender.

In that work, privately educated males were a key issue:

- Only 37 per cent felt “very confident” in understanding what constitutes sexual consent (compared to 59 per cent of students overall)

- Only 34 per cent were “very confident” in how to communicate sexual consent clearly (versus 47 per cent overall)

- Only 41 per cent were “very confident” in how not to pressure others for sex (versus 61 per cent overall)

Our polling in this wave doesn’t have a large enough sample to offer similar demographic breakdowns, but the overall high confidence levels suggest either an improvement in students’ understanding since 2021 or – importantly – potential overconfidence in self-assessment.

For better or worse

Finally, we wanted to know whether students’ health had changed since coming to university. While 39 per cent reported their health has improved (with three per cent saying “much better” and 36 per cent “better”), 27 per cent indicated their health had worsened (23 per cent “worse” and four per cent “much worse”) – and a significant proportion (34 per cent) chose not to respond to this question.

![]()

Many students reported deteriorating mental health since beginning their studies:

Mental health has declined and physical health/pain got worse as well.

Academic pressure has made me feel depressed.

My mental health is no better and I have panic attacks at least two times a week.

Anxiety levels are higher, I feel socially overwhelmed after a day at uni.

Financial pressures emerge as a significant factor negatively impacting both physical and mental wellbeing:

I can’t afford a lot of things. I struggle to buy food period products, and other healthcare. I’m inclined to work when I’m sick because I need to cover tuition and rent.

I can’t afford basic nutrition.

Many students reported having less time or opportunity for physical activity:

Too tired to workout/run most days.

I feel I have less time to exercise. I spend more time on a computer which affects my hands and back.

I was much more physically active before starting university.

Changes in eating habits were commonly mentioned as negatively affecting health:

My diet is a lot worse, and I tend to be generally less healthy.

I put on a lot of weight due to staying in my room all day and not having enough money to afford a good diet.

As I am now living alone, so my eating issues have become worse as I am the one to control what I eat – so I will eat nothing for a month, and then gain all the weight back by giving up and binging.

It’s not all bad news. For those in the “improved” camp, increased physical activity (“I’ve been going to the gym since first year and have really enjoyed doing so”), better nutrition habits (“I have more control and time over my diet”), improved mental wellbeing (“Well at collage I was suicidal but at uni I don’t really have that inkling anymore”), greater autonomy over health choices (“Being more independent and in control of my life has done wonders for my physical and mental health”), and beneficial routines (“The routine has enabled me to keep in touch with my health a lot better”) were all key themes.

The positive experiences suggest that for a significant proportion of students, university can provide both the freedom and structure to develop healthier lifestyles and improved wellbeing.

If it was up to me

When, at the end of the survey, we asked students what they would change about health services if it was up to them, they offered a wealth of practical suggestions.

Mental health services emerged as a top priority, with clear calls for “more therapy sessions,” “expanded mental health services,” and “shorter waiting times or support whilst on waiting lists.” Many emphasised the need for greater coordination: “Less pressure to do so well academically. Student union need to put more pressure on the uni to allocate funds towards mental health services.”

Financial barriers to health featured prominently in student concerns. Suggestions included “lowering the cost of the university gym,” “free prescriptions till you finish uni,” and broader recommendations to “improve student finance so that students can afford to eat healthily.”

Improving access to NHS services was another key theme, with students recommending “a GP on campus perhaps or someone you can talk to before having to go to the GP” and “easier GP registration, shorter wait times for appointments.” Some highlighted specific needs for marginalised groups: “Fast tracking marginalised students who are already forced through forms and waiting list just to access their healthcare.”

Sexual and reproductive health resources were frequently mentioned, with calls for “free condoms across campus,” “free period products,” and “more information about sexual health/like events centred around that, including sexual health for trans people and using inclusive language.”

Many also stressed the need for better information and outreach, suggesting “having a known place to access in a casual manner,” “health advice given in more accessible areas,” and “making clear where and how to access it with a focus on helping international students navigate a new system.”

And several comments addressed broader cultural and systemic issues: “Stop encouraging mid-week drinking, university alcoholism culture is insane”, “More conversations about loneliness, it’s weirdly normalised at uni” and “Address systemic bias in medicine, especially impacting women.”

An agenda for change

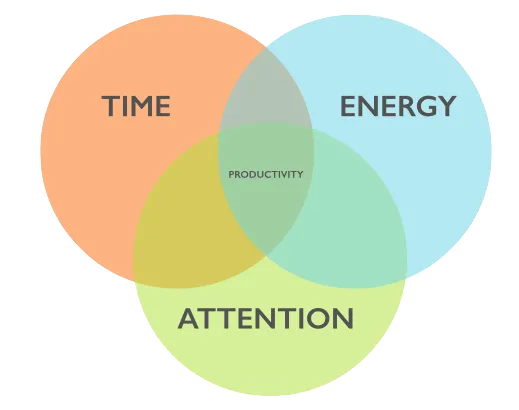

There are bits of good news – but the big picture that emerges from our findings is stark and troubling. 20 per cent of students reporting “very good” health compared to 48 per cent in the general population is a disparity that would prompt immediate intervention in any other population group. But that problematic place in the policy Venn that students are in – both largely young and belonging to DfE, not DHSC – leaves them ignored. This student offers a damning indictment of a system where basic physiological needs compete with academic demands:

I literally went to university at the wrong time with how much it currently costs. It’s impossible to concentrate on my studies without the constant fear of how am I going to eat tonight.

Another speaks of “black mould and damp” while their landlord’s sage advice is to “open a window.” Is this really the backdrop against which we expect student success to happen?

The data reveals a healthcare system fundamentally misaligned with student life realities. Only 65 per cent are registered with a GP where they study, just 17 per cent with a local dentist. And why should they bother? With 49 per cent expressing dissatisfaction with NHS services – “12 hours wait time at A&E is scandalous, people die waiting for ambulances, good luck getting an appointment” – the friction in accessing care hardly seems worth the effort. That we ask international students to pay for it is even more scandalous.

The answers lie partly in our addiction to departmental silos and short-term thinking. No Westminster department champions students as a distinct population with specific health needs deserving of targeted interventions. Universities focus on student retention while the NHS prioritises acute care – and students fall through the gap between.

The South African model of mandatory health modules covering mental, physical and sexual wellbeing offers an interesting approach – yet here we continue treating student health as an afterthought rather than a core educational function, something else that used to be developed in the gap between lectures that’s now filled with the demands of long commutes and punishing part-time work.

What might a solution look like? Perhaps it starts with recognising that today’s “horizontal generation” won’t respond to top-down health messaging. Their peer networks and digital platforms represent not just challenges but opportunities for intervention. Digital solutions that personalise support, peer-to-peer health models, and practical education around cooking and nutrition align with how today’s students actually engage with information. But there’s another critical factor – our lack of comprehensive national data on student health.

The current patchwork of institution-specific surveys and occasional national sampling is simply inadequate. How can we design effective interventions without a robust, longitudinal understanding of student health patterns? A dedicated national student health and wellbeing survey – tracking mental health, food insecurity, nutrition, sleep patterns, and their impact on academic outcomes – isn’t a luxury, it’s a fundamental prerequisite for evidence-based policy. Surely the NSS could take a year off every few years?

Then when it comes to delivery, the answer won’t be found in Whitehall but in our regions and cities. Manchester’s integrated approach to student mental health – where university health services, local NHS trusts, and city council public health teams collaborate on shared priorities – demonstrates what’s possible when student health is approached as a citywide asset rather than an institutional burden. It should both be broadened beyond mental health, and replicated.

And whatever is done really needs to be underpinned by rights – encompassing dual GP registration, affordable healthcare, timely disability diagnosis, health-supporting university policies, and integrated NHS partnerships.

The alternative is to continue watching talented students struggle unnecessarily, their potential diminished by preventable health challenges. A student eating so poorly they “can’t afford basic nutrition” or sleeping in accommodation where “mould grew on my campus room’s walls before I even came in” isn’t just experiencing personal discomfort, they’re living the consequences of policy failure – and paying for it, in more ways than one.

You can download the full deck of our findings from this Belong tranche on student health here.