If I say the word “Serbia”, chances are your mind goes to things like the NATO air attacks of 1999 and the associated Kosovo War, to the breakup of Yugoslavia and to Marshal Tito and maybe – if you’re more historically-minded – to the origins of World War I. It probably doesn’t go to higher education or radical student politics.

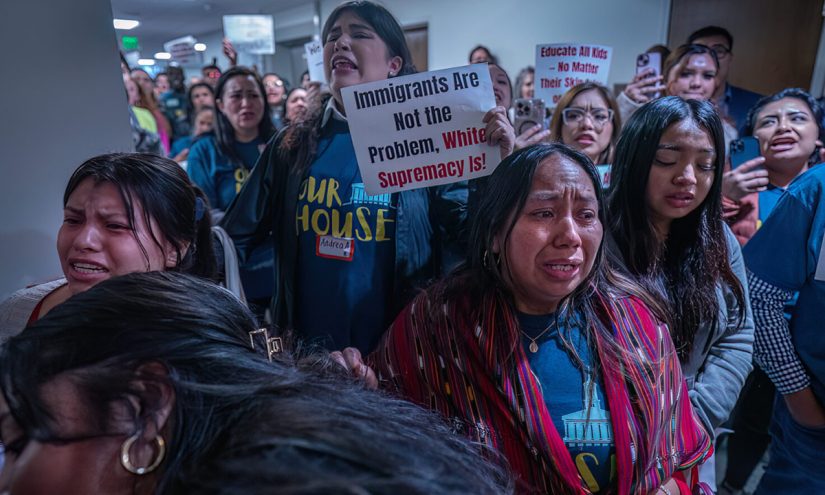

But that’s kind of unfortunate because in fact Serbia’s recent history has had plenty of instances where youth- or student-based movements have had an effect on politics, most notably with respect to the overthrow of Slobodan Milosevic in 2000. And that’s very relevant today, because for the last 18 weeks, Serbia students have been on a campaign to rid the country of the governing Serbian Progressive Party on grounds of corruption. They have formed some extraordinary alliances across civil society leading to regular marches involving tens of thousands of people as well as a series of rotating strikes. The movement has not yet reached its ultimate objective, but it has claimed some notable victories along the way, most notably when the Prime Minister, Milos Vucevic, was forced to resign in January.

With me today to analyze all of this is Jim Dickinson. He’s an associate editor at Wonkhe in London, one of the most remarkable Higher education sites in existence, and to my mind absolutely the best-informed person on the European student politics scene. Jim wrote an excellent summary of the situation in Serbia around the time of the Vucevic resignation, and we thought it was high time to finally bring Jim on the show.

Jim talks about the origins of the protests, its growth and metastasis into a genuinely popular national protest movement and its prospects for future success. Will Serbia end up being like Bangladesh, with students actually forcing regie change? The future is never certain, of course. But what I liked about Jim’s perspective is the way he takes account of the interplay between official student “unions” and an unofficial student “movement” and explains why you need to take account of both to understand the current situation in Serbia.

But enough from me. Let’s turn it over to Jim.

The World of Higher Education Podcast

Episode 3.21 | Students on the Frontlines: The Ongoing Protests in Serbia with Jim Dickinson

Transcript

Alex Usher: Jim, before we get to current day events, tell me—what are student politics normally like in Serbia? Are student unions more about service delivery or activism? Is there just one national student union, or are there multiple ones? Are they organized on a party-political basis? Tell me how it all works in a normal year.

Jim Dickinson: You know, we were there about 14 or 15 months ago, and we were quite impressed. We took a group of UK student unions on a little bus tour, as I do each year to different parts of Europe, and it was quite impressive. Student representation is guaranteed at both the faculty and university levels. Broadly speaking, what is also guaranteed is a student union, which has responsibility for extracurricular activities, as well as for student voice and representing students.

These unions then feed into something called the Student Conference of the Universities of Serbia. What’s interesting—and a few countries in Europe have done this—is that they’ve put the national student union on a statutory footing. So, it’s actually mentioned in legislation. Essentially, they took the National Conference of Rectors, the university association, added an “S” at the front, and set it up as a statutory body that listens to students’ views on higher education.

So, in theory, the legislation establishes representation at the faculty, university, and countrywide levels. Students have the opportunity to elect other students, organize student activities, and be the voice of students—which are broadly the two activities you would expect when you hear the phrase “student union.” Maybe not in the U.S., but certainly in most other parts of the world.

Alex Usher: Is there party political involvement in student unions there?

Jim Dickinson: I mean, this is really interesting. Some people would say there is. But one of the things that’s kind of, I guess, moderately characteristic of the former Yugoslavian and Eastern European countries is that there’s not much open talk of politics.

Sometimes students will align with particular political views, but this isn’t like what we might see in Austria, Germany, or even Finland, where large factional or party political groups of students stand for election to student councils. In Serbia, student unions are framed as being independent from formal politics—pure, in a sense, and separate from direct political involvement.

Now, of course, what actually happens—depending on who you listen to and believe—is that youth branches of political parties do stand in these elections. And depending on the perspective, the government—certainly the current government—is accused of pumping in money and candidates to ensure a level of control in these bodies, much like what might happen in other parts of civil society in the country.

But officially, you don’t see that. In fact, in some of these countries, student unions will even sign documents declaring their complete independence from party politics as a way of signaling, “We’re not about that; we’re about the students.”

Alex Usher: Tell me about the history of student unions getting involved in national politics. I know there’s a history going back to the 1960s in Bulgaria of student involvement in politics.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, there were two major instances in Serbia. In 1996–97, students led protests against what were seen as rigged elections in favor of Slobodan Milosevic. Then in 2000, there was a youth-led—but not student union-led—movement called Otpor, which was the central organizing group that ultimately helped remove Milosevic after the 2000 elections.

Now, obviously, there’s a big mobilization happening today. What’s the connection between those events in the late 90s and early 2000s and what we’re seeing now?

Jim Dickinson: So, ahead of putting student unions—both locally and nationally—on a statutory footing, there were always student groups and associations, often based around faculties or entire universities. Because these groups were relatively loose and voluntary, their level of political interest and influence would fluctuate.

They often got caught up in the kind of events you described—first in the late 80s and then throughout the 90s. And that’s actually quite common. When student groups are loosely organized and not statutory, with many different associations and organizations floating around, they tend to get swept up in big political movements when those arise.

Now, while you’re right that Otpor was technically a youth movement, in practice, it was largely dominated by students. That group of people was widely credited with the overthrow of Milosevic. We’ve actually visited some of the student accommodations where they were organizing, and you can really see how that must have worked—how students would have been talking to each other, coordinating, and mobilizing.

Beyond that point, things get a bit more complicated.

Alex Usher: So, Otpor was student-led, but not student union-led. That’s the distinction here?

Jim Dickinson: Yeah.

Alex Usher: Let’s get to current events. It’s November 1st, 2024. We’re at the railway station in Novi Sad, which is Serbia’s second-largest city. What happens next?

Jim Dickinson: So, a canopy collapses, killing 15 people. By the time they’d completed their assessment about 24 hours later, the death toll had risen to 15. Pretty quickly, rumors started going around that this must be linked to corruption.

There’s been a series of complex, controversial deals linked to some Chinese companies involving infrastructure projects across different parts of the country. So the view was that this was negligence, this was corruption, and that this was another example—right on their doorstep in this big student city—of the Serbian government’s corruption causing harm and death.

Social media videos of the canopy collapsing on young people were pretty heartbreaking, and they went viral very quickly.

What was interesting at that point was that this student group based in the Faculty of Philosophy, which had already been upset about the formal student union elections in their faculty and at the University of Novi Sad, then switched their attention from occupying the faculty building over student union election politics.

They turned their focus to this incident, and quite quickly organized a blockade of the railway station, a blockade of the faculty, and then things kind of swept on from there.

Alex Usher: I get that—it’s understandable why the collapse of a public building might make people upset about corruption. But why is it youth leading this charge? I mean, it’s not unnatural, but it’s also not a given that students would be the ones leading this.

Why them and not some other group in society? Or even opposition parties? Why a small group of disaffected philosophy students?

Jim Dickinson: Well, I mean, in many ways, that is the big question. I’m sure if the Serbian Progressive Party knew the answer, Alex, they’d have stopped it by now.

I think the reality is that all of those involved in formal mechanisms of politics—to some extent—are discredited. And that’s something you see across many political systems, right? There’s a general distrust of politicians and of formal politics, both on the right and the left, in North America and across Europe.

What’s interesting about this group of students is that, in many ways, you’ll find a similar type of group at almost every relatively elite, fairly academic, large university in the world. You’ve got the students who get elected to official positions, wear suits, and sit down with the rector, vice-chancellor, or president. And then there’s this other, rougher-looking group—the ones who like to think about bigger political issues. They’re the ones who will blockade a building, go on a protest, or join a demonstration.

This particular group has probably always been there, usually complaining about student union elections. Then, suddenly, this huge tragedy happens in the city, and they find their big issue—something they can build their movement around.

Often, they talk about building a social movement, but it’s hard to do when the issues they focus on don’t gain traction. This, however, was not a hard issue to mobilize around. It was a tragedy, it was clear-cut, and off the back of that, they took action.

Alex Usher: That’s early November. The protests build and build, and by early December, they’ve secured the resignation of the minister of construction.

So, at this point, what were the student movement’s aims? I get that they were upset about corruption, but what were they actually demanding in these demonstrations? And, given how informal the structure was, who was deciding what those demands were?

Jim Dickinson: It’s really interesting because the demands haven’t really changed since then. Some were directly related to the tragedy, some were broader, and some were focused on higher education.

Actually, if you look at some of the pro-Palestinian blockades and demonstrations in different countries over the past couple of years, they’ve also had a mix of demands like this.

In this case, there were demands to publish all the documents related to the reconstruction of the station. There were calls to ensure that no criminal proceedings would be brought against protest participants. There was also a demand for the dismissal of all public officials who had assaulted students and professors—of which there were quite a few.

Then there were demands related to higher education, like increasing the budget for higher education by 20%. And what’s fascinating is that this list of demands hasn’t really changed.

Now, to answer your question about leadership—one of the defining characteristics of this kind of activism, which some people see as very old-fashioned, is that it’s highly decentralized. Decisions are made collectively, with lots of people sitting in circles discussing them. There’s no single figurehead. They’ve really tried to stick to those principles, even though, historically, that kind of approach sometimes falls apart depending on which allegorical novel you read.

Despite the media’s efforts to identify particular ringleaders or intellectual figures behind the movement, it’s been difficult to pin down a single “bad guy” or figurehead. This stands in stark contrast to the formal student movement, which operates like a traditional hierarchy—a structured system where representatives elect other representatives, and so on.

Alex Usher: So, it’s a little like the Occupy movement?

Jim Dickinson: Yeah, very, very similar.

Alex Usher: Over the course of December and January, the movement builds to the point where, eventually, the prime minister resigns on January 28th. That wasn’t even one of the demands, but it happened anyway. To make that happen, they had to build a coalition—not just within the student movement, which is one thing, but also by making links across civil society, with other groups like legal organizations, unions, teachers’ unions, and so on. How did a group of students manage that, especially given how decentralized their power structure was?

Jim Dickinson: Part of it was about peaceful protest. If you look at historical examples like the Prague protests or the Velvet Revolution, they were always very deliberately peaceful, even though allegations are often thrown at them.

So, good framing was key—absolutely sticking to those principles. And then, night after night, day after day, at each protest, they slowly built support from wider society. As time went on, they captured the imagination of more and more people. First, musicians got involved, then lawyers, then farmers, then taxi drivers.

Each time a new group joined or more people expressed sympathy, the movement grew. And there’s historical precedent for this—going back to the late 80s and early 90s—where what started as a student movement began to voice deeper concerns about corruption, about the direction of the government, about how citizens are treated, and about the growing disconnect between the public and politicians. And they used powerful, simple, visually striking imagery. You might have seen the red hands in some of the protest photos—symbolizing “blood on their hands.” That really resonated with people.

Because these countries have been through this kind of thing before—where students lead the charge and wider society gets behind them—there was this sense that both the students and the broader public felt the weight of history on their shoulders. And from there, it just kept growing.

I was watching over Christmas—one night, there were 10,000 people in the streets, then 12,000 the next night, then 15,000. It just kept building. And every time the government tried to use traditional authoritarian tactics, the protesters held their nerve. They maintained their dignity, and in doing so, they were able to expose the government as authoritarian—cracking down on people who were making perfectly reasonable demands.

Alex Usher: So that’s what’s happening in the streets. But what about the campuses? Are they shut down? Is there a strike? Is there a risk of losing the school year? And how are university administrations dealing with all of this?

Jim Dickinson: That’s a really interesting question.

Quite often—and this is probably true in the UK, certainly true in Canada and the U.S.—when there’s a blockade of a building, an occupation, or a major protest, you still get a form of teaching happening. There are efforts to ensure that education continues, though it might not be the same curriculum the university originally intended, and it often takes on a particular political edge.

So, what they’ve been doing is blockading faculty buildings and university buildings, stopping some administrative functions from happening. But some teaching is still taking place.

Now, whether that translates into exams happening or students receiving certificates at the end of the year varies widely. It depends on the campus, the faculty, and the university.

A lot of that comes down to the level of support for the movement. So, it depends on what you mean by a “write-off.” There’s plenty of evidence that students are still getting an education, but if you’re the kind of student who isn’t interested in any of this and just wants your diploma at the end of the year, then it’s probably a disaster.

Alex Usher: Just so listeners and viewers know, we’re recording this on February 11th—nine days before the air date. This is the 101st day of the protests. What do you think the endgame is here? What would it take at this point for students to achieve the aims you talked about earlier? Or are they going to have to settle for half a loaf?

Jim Dickinson: Well, I mean, it’s really interesting.

Just this week—or maybe it was right at the end of last week, I’ve lost track—they got the 20% budget increase, for example. Nobody expected that to happen two weeks ago. So, slowly, they’re managing to achieve pretty much everything except the dismissal of all the public officials they’ve been demanding.

The problem, of course, is that even if they achieve all of those demands, they still won’t have reached their broader political goal—which is that they believe this is a deeply corrupt government. And while they don’t frame it in party political terms, they think this populist government needs to go. So, the endgame starts to get tricky for them.

They’ve already achieved far more than most people expected. And historically, there’s precedent for this. There were plenty of student uprisings in Eastern Europe in the 1960s that captured the public’s imagination but ultimately didn’t lead to political change.

So, once most of the demands are met and we get closer to the end of the academic year, will the movement start to fizzle out? Who knows?

But for many of the people involved, they’re probably already thinking, “We’ve accomplished a hell of a lot more than we ever thought we would.” And certainly a lot more than the official student movement was ever going to achieve on these issues.

Alex Usher: That brings me to my last question. This has been a success for the student movement—if you can call it that—but not necessarily a success for student unions. So, what do you think the impact will be on more official student organizations going forward? Are unions likely to be supplanted by something a little more anarchist? Or do they just go back to providing the same services they always have?

Jim Dickinson: I mean, look—across the world, the bigger, more sophisticated, and more formally recognized student unions are, and the more access they have to decision-makers, the more mistrust tends to build.

Both the textbooks and reality tell us that when student leaders start spending too much time with people who aren’t students, people begin to see them as too close to decision-makers. And that dynamic exists in every student movement around the world.

The real question for a system like Serbia’s—which has student unions written into the constitution and structured to mirror the conference of rectors, university presidents, and vice-chancellors—is whether, in hindsight, that structure is simply too close to power.

And that comes down to one of two concerns.

If the official student movement hasn’t actually been controlled by the government but just appears too close to it, then there’s some broader reflection needed on the system’s credibility. But if it has been deliberately set up as a way for a corrupt national government to control it—to act as a puppet master—then that carries much bigger implications.

Either way, you have to assume that where student energy is focused will shift. And that’s key because there’s only so much student energy available.

Right now, the biggest problem for formal student unions is that student energy hasn’t gone into electing people to run the social committee or to be the faculty vice president and have a chat with the dean about curriculum.

This year, the bulk of student energy has gone into something bigger—and they’ve won. That’s something a lot of people, both within the sector and seemingly within the country as a whole, will have to reckon with.

Alex Usher: Jim, it’s been a pleasure. Thanks so much for joining us today. And I just want to take a moment to thank our excellent producers, Sam Pufek and Tiffany MacLennan, as well as you—our viewers, listeners, and readers—for joining us. If you have any questions about today’s episode, don’t hesitate to reach out at [email protected]. Never miss an episode of The World of Higher Education podcast—subscribe to our YouTube channel today. Next week, we’re off, but join us two weeks from today when our guest will be Israeli scholar Maya Wind. She’s a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Riverside, and the author of Towers of Ivory and Steel: How Israeli Universities Deny Palestinian Freedom. Bye for now.

*This podcast transcript was generated using an AI transcription service with limited editing. Please forgive any errors made through this service.