I am busy, stressed, perhaps feeling the first prickles of burnout. I feel tension may be getting between me and my students, colleagues, family, and others I care about. I feel that my mind is out of my control, going down rabbit holes, ruminating on the past or stressing about the future. How do I dip my toe into mindfulness, to see if it could work for me, so I can be better for myself and others?

However, my plate is full: I do not have the capacity to take on any new things. So any suggestions must not take much time.

Also, I have never been a fan of the self-help industry and not sure I am such a spiritual person. I am just not interested in woo-woo. Finally, I am not really convinced there’s anything wrong with me that needs to be fixed.

I have heard that mindfulness may be able to help with runaway thoughts and the associated stress, anxiety, and burnout. How can I dip my toe in those calm waters in a way that satisfies all my concerns?

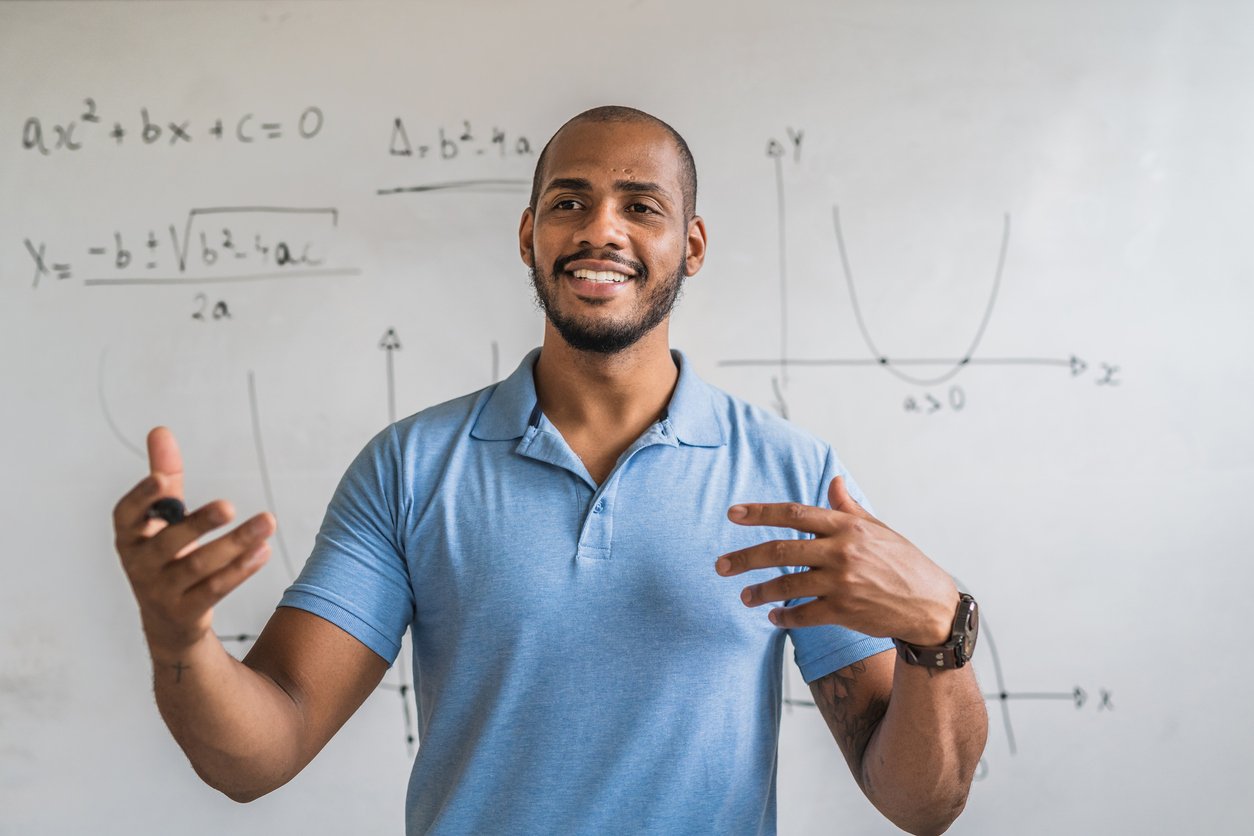

First, you are not alone. People in the helping professions: teachers, counselors, aides, advisors, and others, need help. Stress, anxiety, and burn-out remain at unsustainable levels. People in these professions are especially at risk because they must help others address their own stressors, anxieties, and fears to do their jobs. Failure to do this effectively and consistently means the teacher does not teach, advisors do not advise, and so on. It can also mean that professionals internalize their clients’ challenges, creating a vicious circle. Burnout—a state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion, social detachment, and reduced self-confidence —can result from excessive workload and chronic workplace stress that hasn’t been effectively managed. This stress often stems from lacking both the necessary tools and authority to perform our jobs well and achieve meaningful goals. Can mindfulness help?

The scientific literature supports the notion that mindfulness practice, defined by Jon Kabat-Zinn as “Awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally and with acceptance” can reduce stress, anxiety, and burnout. For example, a 2024 meta-analysis of 49 studies found that two-thirds of mindfulness based interventions reduced the effects of burnout, especially emotional exhaustion.

However, intention matters. Perhaps there really is nothing to fix; no self to improve. People should practice mindfulness not to reduce stress or anxiety or to sleep better, but a good thing to do for its own sake. Tightly focusing on goals like these can make them recede because such goals emphasize the gap between where we are and where we want to be, heightening our dissatisfaction with the present. It also reinforces the falsehood that there’s something wrong with us.

“When you try to stay on the surface of the water, you sink; but when you try to sink, you float.” — Alan Watts

On the contrary, mindfulness is about being open and aware of the present moment, without judgment. While we’re defining terms, meditation refers to the many practices and ways of being deliberately mindful with intention, concentration, and compassion. It can occur sitting down, walking, doing certain tasks, or in moments between tasks.

The best reason to practice is not for self-improvement. It is because it is literally the most human thing we can do. Imagine asking an AI to be mindful for us or for itself. Mindful moments are when we are our best, truest selves, when we experience our connection with the world around us. Ideally, it will make us happier and better for others, but this is not the reason to do it, not least because everyone’s experience is different.

To get started, just experiment. Play around with different techniques, practices, and ideas and see what works for you. Try an experiment from the list below for a minute or two, while you change tasks or locations, so they don’t take away time from other to-dos. (Place a sticky-note reminder on your desk.) Every time you do one of these, give yourself a figurative pat on the back.

Here are ten tiny mindfulness experiments that anyone can do without any practice or instruction:

- Just notice things as you go about your day. Experience novelty in the quotidian.

- Breathe deliberately and deeply. Experience all of the different sensations that you can, without judgment.

- Scan the body from head to toe. Experience all the different sensations that arise, without labels.

- When working with students or others, see if you can relax the focus on the self when it appears. Turn off self-view on Zoom calls.

- Let yourself feel connection with and compassion for others, even for those you don’t naturally feel positive about. Experience this in the body, not just cognitively.

- Be aware of the thoughts that come and go in your consciousness, without you having to do anything about them. Hear unconstructive thoughts in a silly voice (I use Daffy Duck.)

- When eating, for one piece of food, slow down to one-tenth your normal speed and experience all of the sights, sounds, and sensation of eating it.

- The next time an unwanted sensation or thought occurs, relax the impulse to resist it. Instead, try RAIN: Recognize the sensation; Accept it; Investigate it (i.e. learn from it); and Nurture yourself.

- Look at your feet. Slowly scan up the body. What is present when you attempt to look above the chest? What happens when you look for the looker? (This is a way to loosen the hold of our ego and relax.)

- Take a day off from non-essential smartphone notifications and social media. Reflect on the effects.

You will notice as you try these activities that the mind will wander. That is natural and to be welcomed. The point of being mindful isn’t to eliminate thoughts, but rather to build a practice of returning to the object of attention when you want to, so that you don’t remain in the dreamlike state of being lost in thought.

You will also notice how everything you experience changes on its own. Many of the ideas and sensations you experience you don’t have to do anything about, they just come and go on their own. You may even notice that ideas and sensations themselves don’t come packaged with good/bad judgements: we just tend to automatically and mindlessly layer those on ourselves. Experiment with just being with experiences, pleasant or otherwise, and seeing what that’s like.

Where to go from there? There are many organizations, podcasts, and apps to try (I like Waking Up for its variety of teachers, learning opportunities, and guided meditations). Consider setting a time every day for a short “sit”, for example, as part of your morning routine. I have found mindful practice an excellent supplement to other kinds of self-care including psychotherapy. Consider also working with a therapist on issues relating to stress, anxiety, and similar challenges. Finally, invite a friend or loved one to join you in these experiments. Sharing can make the experiences more fun, meaningful, and help you to persist.

To be sure, reducing stress and burnout it’s not only up to us as individuals. As employees, labor union members and voters, we must also advocate for employer and government policies that support safer, more sustainable working and living environments. Excessive workloads, lack of autonomy, poor labor relations, job insecurity, and low pay may all contribute to chronic stress and burnout. Managers and policymakers must address these issues even as they support worker mindfulness and self-care.

In sum, mindfulness need not be time consuming, woo-woo, unscientific, or frustrating. Be playful and experimental about it. Try some of the activities above during the interstices of your day. Over time, you will see what works for you and create habits and rituals that make them more automatic. The Buddhist teacher Pema Chodron argues that over time, as life gets smoother, we build capacity to “move closer” to help people in need. Isn’t this what all of us in the helping professions need?

Note: The above reflects my personal opinion only and may not reflect the views or position of CUNY or BMCC.

Brett Whysel is a lecturer in finance and decision-making at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY, where he integrates mindfulness, behavioral science, generative AI, and career readiness into his teaching. He has written for Faculty Focus, Forbes, and The Decision Lab. He is also the co-founder of Decision Fish LLC, where he develops tools to support financial wellness and housing counselors. He regularly presents on mindfulness and metacognition in the classroom and is the author of the Effortless Mindfulness Toolkit, an open resource for educators published on CUNY Academic Works. Prior to teaching, he spent nearly 30 years in investment banking. He holds an M.A. in Philosophy from Columbia University and a B.S. in Managerial Economics and French from Carnegie Mellon University.

References

Brach, T. (2024). RAIN: Recognize, allow, investigate, nurture. Retrieved October 2, 2025, from https://www.tarabrach.com/rain/

Chödrön, P., & Kullander, J. (2022, July 17). Turning toward pain: An interview with Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön. Beliefnet. https://www.beliefnet.com/wellness/health/physical-health/pain-management/turning-toward-pain.aspx

Ford, B. Q., & Mauss, I. B. (2014). The paradoxical effects of pursuing positive emotion: When and why wanting to feel happy backfires. In J. Gruber & J. T. Moskowitz (Eds.), Positive emotion: Integrating the light sides and dark sides. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199926725.003.0020

Langer, E. J. (2023). The mindful body: Thinking our way to chronic health. Ballantine Books.

Steiner, E. D., Levine, P. R., Doan, S., & Woo, A. (2025). Teacher well-being, pay, and intentions to leave in 2025: Findings from the State of the American Teacher Survey (RR-A1108-16). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-16.html

Watts, A. W. (1951). The wisdom of insecurity: A message for an age of anxiety (p. 40). Pantheon Books.