Multiple faculty members connected with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s controversial school that had been billed as promoting civil discourse have resigned from leadership roles, citing strong disagreements with the dean who appointed them.

One such professor went so far as to call the School of Civic Life and Leadership an “unmitigated disaster.” The recent group of resignations adds to past departures by professors who said the school’s earlier focus had shifted and narrowed under Jed Atkins, its first permanent dean. Much of the current controversy centers on Atkins’s handling of searches for new faculty.

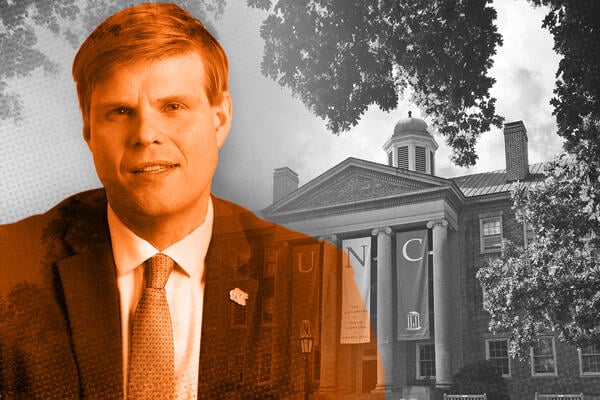

Atkins, who ran Duke University’s Civil Discourse Project and chaired its classical studies department before moving to UNC a year ago, defended the hiring procedures in a statement to Inside Higher Ed. He didn’t provide an interview.

The school’s birth was mired in controversy. It’s an example of the civil discourse centers—which critics have called conservative centers—that higher education leaders and Republican state lawmakers have been establishing at public universities. For more than two years, debate over the UNC school has been tinged by accusations that its supporters are motivated by conservative politics and its opponents by leftism.

But the recent resignation letters from the school’s former supporters suggest disagreements that resist characterization as a simple left-right divide. The criticism of the faculty search procedures involves allegations that faculty input, including from the school’s search committee and advisory board members, was disregarded.

The university’s media relations arm said that Chapel Hill policy requires four full professors to vote in faculty hirings. The advisory board contained such professors, who predated the school’s creation. But the Chapel Hill spokespeople said that in “all faculty appointment matters, the votes of faculty are advisory to the dean,” whose recommendation eventually goes to the universitywide appointments, promotion and tenure committee that advises the provost. The provost has hiring power, though the Chapel Hill Board of Trustees must approve awarding tenure.

Inger S. B. Brodey, an English and comparative literature professor whom Atkins chose as one of two associate deans, kicked off the recent round of resignations. She wrote to Atkins on Feb. 28 that she still believes strongly in the school’s “original mission, which, as I understand it, includes an emphasis on civil discourse across difference, preparation for citizenship and fruitful lives through studying global great books, promoting scientific literacy and assembling a diverse faculty from many disciplines.”

However, Brodey wrote, the school “has lost sight of its mission in all these areas and is unlikely to make the lasting positive impact that I and the other inaugural faculty had hoped for. For this and other reasons, I hereby resign as associate dean.”

Inside Higher Ed obtained the email and other documents mentioned in this story from sources who were either anonymous or whose identities are known but who requested anonymity.

In January, before that resignation email, Brodey sent Atkins a much longer message on why she was resigning from a faculty search committee. Brodey confirmed the authenticity of both emails to Inside Higher Ed.

“While it may be within the dean’s power to intervene at every stage of the search and add/remove names, overruling the opinions of the committee, I have never seen this power executed outside of SCiLL,” wrote Brodey, using the school’s acronym. She serves in multiple departments of Chapel Hill.

“I don’t have any confidence that the search committee will have any actual effect on the final roster of individuals hired,” she wrote. She also said, “I don’t think this list differs in any substantial way from the list of concerns David enumerated in our last meeting, when he resigned from the search.”

That’s a reference to David Decosimo, SCiLL’s remaining associate dean. Asked for comment, Decosimo replied in an email, “I’m on parental leave this semester, so won’t comment at this time.”

This faculty search, which began in the fall, wasn’t small. Atkins has said it resulted in eight offers to candidates. Brodey was even more critical of the process in an email to The Daily Tar Heel, which reported earlier on her resignation. She told the student newspaper that there were “improprieties, slander, vindictiveness and manipulation” surrounding the search.

Dustin Sebell, a SCiLL professor who chaired the search committee (the three members were him, Brodey and Decosimo), disagreed with Brodey in an email. Sebell wrote that Atkins hadn’t overruled the committee.

“You personally recorded the names of the 20 finalists on behalf of the search committee and emailed them to me,” Sebell wrote. He said, “The committee was fully aware that we had only 16 spots for on campus interviews … it was a mathematical certainty that the dean would exercise some discretion in the selection of finalists from our list.”

On March 7, Jon Williams, a Chapel Hill economics professor, resigned from SCiLL’s advisory board in an email to Atkins, Chapel Hill chancellor Lee Roberts, provost Chris Clemens and vice provost for faculty affairs Giselle Corbie. Williams alleged that Atkins had ignored all advice and that he felt like he was “nothing more than one of four warm bodies to achieve the dean’s shadowed objectives.”

“There is no need for an advisory board if the dean ignores any advice that isn’t simply confirmation,” Williams wrote. “More troubling, over the last six weeks, I’ve seen incivility and dysfunction, biased and unfair processes, a complete disregard for governance, and a willingness to deceive and misrepresent that is unlike anything I’ve witnessed in my 15 years in academia.”

Williams ended with, “I cannot see how SCiLL will emerge from this troubled beginning without new leadership.” He declined an interview with Inside Higher Ed, writing in an email, “I will confirm that I resigned and that my concerns center around” Atkins.

He wrote in his resignation email that he still appreciates “the need for a place on campus for students to learn how to critically evaluate and debate the most challenging and controversial topics. Simply put, I’m often in a tiny minority among faculty in my views and opinions, so I appreciate how difficult students may find it to engage in open discussion.”

Three days after Williams’s resignation from the advisory board, Fabian Heitsch, a physics and astronomy professor, followed suit with his own email to Atkins, Roberts, Clemens and Corbie. Heitsch specifically mentioned issues with personnel decisions, but he didn’t provide many specifics or respond to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment.

“In my year of service on the advisory board, I have witnessed its advice on personnel decisions being ignored on three separate occasions,” Heitsch wrote. He said, “It seems as if the advisory board is being used only as a formality instead of as a body of experience and strategy.”

Heitsch said the advisory board “is to provide formal advice to the dean and director. As I understand it, formal advice is not limited to providing the votes to confirm leadership’s decisions.” He wrote that he still supports the school’s “original mission” and that he “will gladly continue to serve as a curricular fellow.”

Not the First Resignations

These weren’t the first Chapel Hill faculty who—having come to the university before the school’s creation—affiliated themselves with it only to then reduce their involvement or fully withdraw after Atkins’s appointment, citing a changed direction for the school. One who stepped back last year was Matthew Kotzen, Chapel Hill’s philosophy department chair.

But the newer resignations have come alongside stronger denunciations—at least publicly. And Kotzen himself increased his past public criticism in a statement to Inside Higher Ed.

“The original mission of SCiLL was to model and to teach essential skills related to productive engagement with democratic civic institutions, including respectful dialogue across ideological difference,” Kotzen wrote. “Unfortunately, it has become increasingly clear that Dean Atkins is committed to none of those values.”

Kotzen said Atkins “has an extremely narrow conception of acceptable viewpoints and approaches and has demonstrated almost no openness to feedback from others on the faculty, including those that he himself selected for their role. Dean Atkins has fostered a dysfunctional anti-intellectual culture at SCiLL that rewards hostility, dishonesty and self-righteousness in the pursuit of his ideological and personal aims. That disqualifies him from holding any leadership position at UNC.”

Atkins told Inside Higher Ed in an email that “the advisory committee’s function in faculty searches is to help assess the merits of our finalists and to cast an advisory vote on each finalist.” He wrote, “In SCiLL’s most recent national search, our faculty rigorously evaluated our applicants’ strengths and promise.”

“Finalists traveled to campus from three continents, gave teaching demonstrations to students, presented on their research and engaged with our faculty in more informal settings,” Atkins said. “After these campus interviews, SCiLL’s tenure-line faculty met and voted on our finalists; they recommended a strong slate of candidates for appointment.”

Danielle Charette James, a SCiLL assistant professor, told Inside Higher Ed in an email that “our process was highly collaborative, and the candidates who received offers earned overwhelming, and in some cases unanimous, support from SCiLL’s core faculty.”

Chapel Hill’s media relations arm emailed a statement to Inside Higher Ed saying, “SCiLL’s faculty searches honored all university rules and procedures. Applicants were advanced on the basis of merit and fit with the advertised positions. We are looking forward to welcoming an outstanding group of new faculty to campus next fall.”

‘Dress Rehearsal’

Back in January 2023, Chapel Hill’s Board of Trustees passed a resolution asking the campus administration to “accelerate its development of a School of Civic Life and Leadership.” Faculty said they were caught off guard because they didn’t know a whole school was in development. David Boliek, then chair of Chapel Hill’s board, called it an effort to “remedy” a shortage of “right-of-center views” on campus. Clemens, the provost and a self-described conservative, promoted the school.

In the fall of 2023, the Republican-controlled State Legislature passed a law that required Chapel Hill to establish the school. The campus couldn’t back out even if it desired to. Clemens had the final say in hiring Atkins as dean, at least before the Chapel Hill board signed off.

And despite the past faculty objections, current Chapel Hill professors, including Brodey, Kotzen and Williams, affiliated with the initiative.

But faculty aren’t the only ones critiquing the recent faculty search. Clemens, who didn’t return requests for comment for this article, at one point ordered a stop to the faculty searches.

In a January email to Atkins, Clemens said there were financial limitations. Instead of progressing toward hiring tenure-track faculty, Clemens said, “SCiLL should initially focus on hiring teaching track professors to support large enrollments in the general education curriculum.” So, he said, he was canceling the searches.

The provost also seemingly referenced issues beyond budgets.

“Your search committee and voting faculty for these searches is small; smaller even than the number of people you were authorized to hire,” Clemens wrote. “Moreover, some of them have just arrived in Chapel Hill. All new teams must learn to work together, and this ‘dress rehearsal’ has hopefully been a learning experience for all.”

He then wrote, with original emphasis included, “I want to emphasize how important it is for a School of Civic Life and Leadership to serve as a model of civic life and civil discourse. Given the intense scrutiny and attention on this school, everything you do—including faculty searches—must be exemplary, both to give the candidates confidence in SCiLL and to give the rest of the university confidence in those you hire. I will address how we can fulfill those expectations for future searches in collaboration with SCiLL leadership and with HR.”

Clemens sent that on a Friday. But by the following Monday, he said the searches were back on after Chancellor Roberts “committed sufficient funds.”

The criticism of Atkins continues. On Monday, Atkins accepted Williams’s resignation and rebutted his critiques. Williams responded in an email by saying he resigned to protect his reputation, “because SCiLL is currently an unmitigated disaster.”

He accused Atkins of “hiding behind accusations that wokeness has derailed your efforts,” something Williams called “absolutely ridiculous given that you completely lost the support of folks like myself that have spent a decade battling it on campus.”

“It’s your failure alone,” Williams wrote. “Time to own it.”