What we learn in school comes in part, and perhaps the smaller part, through the manifest curriculum. We first learn skills—how to read and write and do arithmetic—and then we begin the long process of learning subject matter. This is what school is intended to impart to us. We are taught, in all manner of visible ways, how to do things and what we ought to know.

From the start, we learn other things as well: how to follow rules, how organizational hierarchies work and how we can be held accountable for misbehavior. We learn, too, what matters to other members of our tribe—individual achievement, success in competition—and what makes some people more important than others. These are elements of the hidden curriculum, or what might be called the meta-lessons of school.

By the time students get to college, they have already absorbed many such lessons, or they wouldn’t be here at all. But college offers a new set of meta-lessons. These are lessons about knowledge itself: how to assess it, how to identify its varieties, how it’s created. To miss out on these lessons, as can happen, is to miss out on what is most valuable about a college education.

The meta-lessons of college come with political implications. As political scientists and others have shown, there is a diploma divide in this country. On one side is the largest and most loyal group of Trump supporters: whites without a college degree. On the other side are those with bachelor’s or advanced degrees, who tend to vote Democratic. Clearly, there is something about a college education that makes a difference in political behavior.

Some analysts have argued that the divide reflects a feeling on the part of non-college-educated whites of being left behind in a high-tech economy. These feelings of disappointment and failure in turn make this group receptive to racist dog whistles—DEI policies are giving undeserving minorities unfair advantages!—used by right-wing politicians. Others have argued that the divide reflects an indoctrination into liberalism that students experience in college.

Analyses of the diploma divide have been going on for nearly a decade, since soon after Trump’s first election in 2016. Sorting out this body of work would require a separate essay. Here I am proposing only that the divide owes in part to the meta-lessons of college, in that these lessons should, in theory, make people less susceptible to political hucksterism, emotionally manipulative rhetoric and the embrace of simple nostrums as solutions to complex social problems.

And so it seems worthwhile for pedagogical and civic reasons to put the meta-lessons of college on the table. I identify seven that strike me as crucial. No doubt others’ lists will vary, as will ideas about how much these lessons matter. Yet it seems to me that these lessons, if taken to heart and applied, are what enable college graduates to sort sense from nonsense, fact from fiction and rational argument from demagoguery. Here, then, are the lessons.

- Empirical claims are distinct from moral claims. To say, for example, that the death penalty deters capital crimes is to make an empirical claim. It isn’t a matter of opinion. With the right data, we can determine whether this claim is true or not (it’s not). To say the death penalty is wrong is to make a moral claim that must be addressed philosophically. Students who learn how to make this fundamental distinction are less likely to be distracted by philosophical apples when empirical oranges are the issue. Whether revenge feels like justice, they will understand, has no bearing on its practical consequences.

- Evidence must be weighed. Arguments gain credence when supported by evidence, especially when it comes to empirical matters. But the importance of assessing the quantity and quality of supporting evidence is less widely appreciated. To the extent that college students learn how to do this—and acquire the inclination to do it even when an argument or analysis is emotionally appealing—they are less likely to be misled by anecdotes, atypical examples or cherry-picked studies that employ weak methods.

- Errors often hide in assumptions. An argument can be persuasive because it sounds good and appears to be backed by evidence. Yet it can still be wrong because it starts from false premises. A key meta-lesson in this regard is that it is important to examine the foundations of an argument for logical or empirical cracks that make it unsound. To always ask, “What does this argument take for granted that might be wrong?” is a valuable habit of mind, a habit nurtured in college classrooms where students are taught, likely at the cost of some discomfort, to interrogate their own beliefs.

- Logic matters. Poets might want to express the contradictory multitudes they contain, but those who purport to offer serious political analysis must respect logic, the absence of which ought to be discrediting. If your theory of social attraction says birds of a feather flock together, except when opposites attract, you had better find a higher-order principle that reconciles the contradiction or admit that you’re just making stuff up. The meta-lesson that logic matters, again learned through disciplined skepticism, provides at least partial protection against toxic nonsense.

- Truth can be elusive, but it is not an illusion. Truth has taken a beating in recent decades under the influence of postmodernist social theories. Even so, it remains possible, unless we abandon the idea of evidence altogether, to have confidence that some empirical claims are true, in the ordinary sense of the term. Students learn this in their subject-matter courses; they learn that research can turn up real facts, that some empirical claims warrant more confidence than others and that some claims are demonstrably wrong. This meta-lesson can help ward off the nihilism—the paralyzing feeling that it is impossible to know what to believe—that often arises in the face of a blizzard of lies.

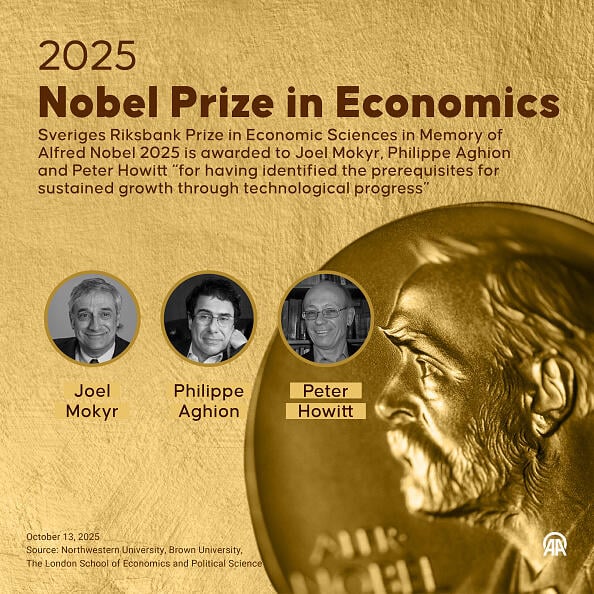

- Expertise is real. In college, students encounter people who have spent years studying, and possibly creating new knowledge about, some aspect of the natural or social world. These people—scientists, scholars—know more about their subject-matter areas than just about anyone else. The meta-lesson, hopefully one that sticks, is that hard-won expertise exists, and while experts might not always be right, they are more reliable sources of analysis than glib pundits and unctuous politicians.

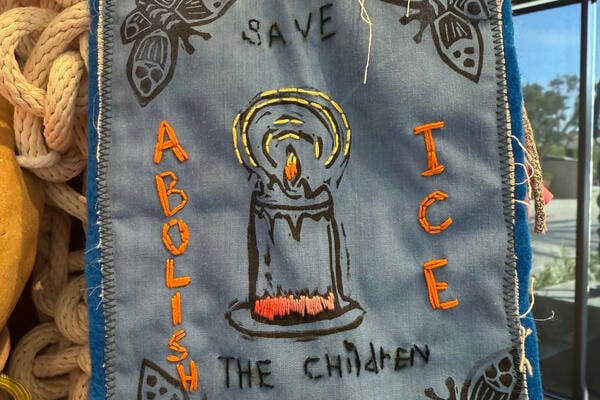

- A slogan is not an analysis. Slogans that are useful as rallying cries often deliver no real understanding. “Defund the police” is as useful a guide to crime prevention as “Guns don’t kill people; people kill people” is to addressing the problem of gun violence. Other examples abound. The important meta-lesson is that a useful, sense-making analysis of a complex problem is likely to be complex in itself—and it would be wise, as college students ought to learn, not to forsake complexity in favor of a catchy sound bite.

The suggestion that these meta-lessons inoculate college graduates against irrationality and unreason stumbles against the fact that college graduates can still succumb to these maladies. It’s hard to know whether this occurs because the lessons were not learned, or if circumstances make it expedient to forget them. I suspect that when well-educated people—the JD Vances and Josh Hawleys of the world—appear not to have learned these lessons, what we’re seeing is a cynical performance in the service of self-interest. The lessons were indeed learned, I further suspect, but are applied perversely, as when the physician becomes a skilled poisoner.

Nonetheless, the diploma divide is real; a college education, on average, all else being equal, does seem to make people more resistant to misinformation, comforting myths, evidence-free claims about the world, irrational emotional appeals, illogical arguments and outright lies. This is as it should be; it is higher education having the effects it ought to have, effects that can impede authoritarianism. To be sure, college is not the only place where this kind of critical acumen is acquirable. College is just the place best organized to cultivate it.

In the end, the issue is not the diploma divide. For educators, the issue should be how to do a better job of transmitting the meta-lessons of college, presuming a shared belief in the value of these lessons for the intellectual and civic benefits they can yield. Spotlighting these elements of the “hidden curriculum” of course means they are not hidden at all, and so when critics insist that our job is to teach students how to think, we can say, “Yes, look here: That is exactly what we’re doing.”