One of the basic expectations of a system of regulation is consistency.

It shouldn’t matter how prestigious you are, how rich you are, or how long you’ve been operating: if you are active in a regulated market then the same rules should apply to all.

Regulatory overreach can happen when there is public outrage over elements of what is happening in that particular market. The pressure a government feels to “do something” can override processes and requirements – attempting to reach the “right” (political or PR) answer rather than the “correct” (according to the rules) one.

So when courses at Oxford Business College were de-designated by the Secretary of State for Education, there’s more to the tale than a provider where legitimate questions had been raised about the student experience getting just desserts. It is a cautionary tale, involving a fascinating high-court judgment and some interesting arguments about the limits of ministerial power, of what happens when political will gets ahead of regulatory processes.

Business matters

A splash in The Sunday Times back in the spring concerned the quality of franchised provision from – as it turned out – four Office for Students registered providers taught at Oxford Business College. The story came alongside tough language from Secretary of State for Education Bridget Phillipson:

I know people across this country, across the world, feel a fierce pride for our universities. I do too. That’s why I am so outraged by these reports, and why I am acting so swiftly and so strongly today to put this right.

And she was in no way alone in feeling that way. Let’s remind ourselves, the allegations made in The Sunday Times were dreadful. Four million pounds in fraudulent loans. Fake students, and students with no apparent interest in studying. Non-existent entry criteria. And, as we shall see, that’s not even as bad as the allegations got.

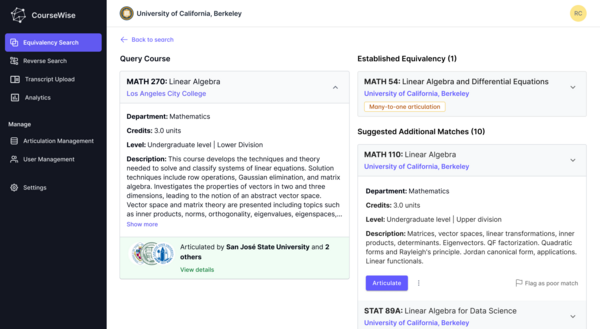

De-designation – removing the eligibility of students at a provider to apply for SLC fee or maintenance loans – is one of the few levers government has to address “low quality” provision at an unregistered provider. Designation comes automatically when a course is franchised from a registered provider: a loophole in the regulatory framework that has caused concern over a number of years. Technically an awarding provider is responsible for maintaining academic quality and standards for its students studying elsewhere.

The Office for Students didn’t have any regulatory jurisdiction other than pursuing the awarding institutions. OBC had, in fact, tried to register with OfS – withdrawing the application in the teeth of the media firestorm at the end of March.

So everything depended on the Department for Education overturning precedent.

Ministering

It is “one of the biggest financial scandals universities have faced.” That’s what Bridget Phillipson said when presented with The Sunday Times’ findings. She announced that the Public Sector Fraud Authority would coordinate immediate action, and promised to empower the Office for Students to act in such cases.

In fact, OBC was already under investigation by the Government Internal Audit Agency (GIAA) and had been since 2024. DfE had been notified by the Student Loans Company about trends in the data and other information that might indicate fraud at various points between November 2023 and February 2024 – notifications that we now know were summarised as a report detailing the concerns which was sent to DfE in January 2024. The eventual High Court judgement (the details of which we will get to shortly) outlined just a few of these allegations, which I take from from the court documents:

- Students enrolled in the Business Management BA (Hons) course did not have basic English language skills.

- Less than 50 per cent of students enrolled in the London campus participate, and the remainder instead pay staff to record them as in attendance.

- Students have had bank details altered or new bank accounts opened in their name, to which their maintenance payments were redirected.

- Staff are encouraging fraud through fake documents sent to SLC, fake diplomas, and fake references. Staff are charging students to draft their UCAS applications and personal statements. Senior staff are aware of this and are uninterested.

- Students attending OBC do not live in the country. In one instance, a dead student was kept on the attendance list.

- Students were receiving threats from agents demanding money and, if the students complained, their complaints were often dealt with by those same agents threatening the students.

- Remote utilities were being used for English language tests where computers were controlled remotely to respond to the questions on behalf of prospective students.

- At the Nottingham campus, employees and others were demanding money from students for assignments and to mark their attendance to avoid being kicked off their course.

At the instigation of DfE, and with the cooperation of OBC, GIAA started its investigation on 19 September 2024, continuing to request information from and correspond with the college until 17 January 2025. An “interim report” detailing emerging findings went to DfE on 17 December 2024; the final report arrived on 30 January 2025. The final report made numerous recommendations about OBC processes and policies, but did not recommend de-designation. That recommendation came in a ministerial submission, prepared by civil servants, dated 18 March 2025.

Process story

OBC didn’t get sight of these reports until 20 March 2025, after the decisions were made. It got summaries of both the interim and final reports in a letter from DfE notifying it that Phillipson was “minded to” de-designate. The documentation tells us that GIAA reported that OBC had:

- recruited students without the required experience and qualifications to successfully complete their courses

- failed to ensure students met the English language proficiency as set out in OBC and lead provider policies

- failed to ensure attendance is managed effectively

- failed to withdraw or suspend students that fell below the required thresholds for performance and/or engagement;

- failed to provide evidence that immigration documents, where required, are being adequately verified.

The college had 14 days to respond to the summary and provide factual comment for consideration, during which period The Sunday Times published its story. OBC asked DfE for the underlying material that informed the findings and the subsequent decision, and for an extension (it didn’t get all the material, but it got a further five days) – and it submitted 68 pages of argument and evidence to DfE, on 7 April 2025. Another departmental ministerial submission (on 16 April 2025) recommended that the Secretary of State confirm the decision to de-designate.

According to the OBC legal team, these emerging findings were not backed up by the full GIAA reports, and there were concerns about the way a small student sample had been used to generalise across an entire college. Most concerningly, the reports as eventually shared with the college did not support de-designation (though they supported a number of other concerns about OBC and its admission process). This was supported by a note from GIAA regarding OBC’s submission, which – although conceding that aspects of the report could have been expressed more clearly – concluded:

The majority of the issues raised relate to interpretation rather than factual accuracy. Crucially, we are satisfied that none of the concerns identified have a material impact on our findings, conclusions or overall assessment.

Phillipson’s decision to de-designate was sent to the college on 17 April 2025, and it was published as a Written Ministerial Statement. Importantly, in her letter, she noted that:

The Secretary of State’s decisions have not been made solely on the basis of whether or not fraud has been detected. She has also addressed the issue of whether, on the balance of probabilities, the College has delivered these courses, particularly as regards the recruitment of students and the management of attendance, in such a way that gives her adequate assurance that the substantial amounts of public money it has received in respect of student fees, via its partners, have been managed to the standards she is entitled to expect.

Appeal

Oxford Business College appealed the Secretary of State’s decision. Four grounds of challenge were pursued with:

- Ground 3: the Secretary of State had stepped beyond her powers in prohibiting OBC from receiving public funds from providing new franchised courses in the future.

- Ground 1: the decision was procedurally unfair, with key materials used by the Secretary of State in making the decision not provided to the college, and the college never being told the criteria it was being assessed against

- Ground 4: By de-designating courses, DfE breached OBCs rights under Article 1 of the First Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights (to peaceful enjoyment of its possessions – in this case the courses themselves)

- Ground 7: The decision by the Secretary of State had breached the public sector equality duty

Of these, ground 3 was not determined, as the Secretary of State had clarified that no decision had been taken regarding future courses delivered by OBC. Ground 4 was deemed to be a “controversial” point of law regarding whether a course and its designation status could be a “possession” under ECHR, but could be proceeded with at a later date. Ground 7 was not decided.

Ground 1 succeeded. The court found that OBC had been subject to an unfair process, where:

OBC was prejudiced in its ability to understand and respond to the matters of the subject of investigation, including as to the appropriate sanction, and to understand the reasons for the decision.

Judgement

OBC itself, or the lawyers it engaged, have perhaps unwisely decided to put the judgement into the public domain – it has yet to be formally published. I say unwisely, because it also puts the initial allegations into the public domain and does not detail any meaningful rebuttal from the college – though The Telegraph has reported that the college now plans to sue the Secretary of State for “tens of millions of pounds.”

The win, such as it is, was entirely procedural. The Secretary of State should have shared more detail of the findings of the GIAA investigation (at both “emerging” and “final” stages) in order that the college could make its own investigations and dispute any points of fact.

Much of the judgement deals with the criteria by which a sample of 200 students were selected – OBC was not made aware that this was a sample comprising those “giving the greatest cause for suspicion” rather than a random sample, and the inability of OBC to identify students whose circumstances or behaviour were mentioned in the report. These were omissions, but nowhere is it argued by OBC that these were not real students with real experiences.

Where allegations are made that students might be being threatened by agents and institutional staff, it is perhaps understandable that identifying details might be redacted – though DfE cited the “”pressure resulting from the attenuated timetable following the order for expedition, the evidence having been filed within 11 days of that order” for difficulties faced in redacting the report properly. On this point, DfE noted that OBC, using the materials provided, “had been able to make detailed representations running to 68 pages, which it had described as ‘comprehensive’ and which had been duly considered by the Secretary of State”.

The Secretary of State, in evidence, rolled back from the idea that she could automatically de-designate future courses without specific reason, but this does not change the decisions she has made about the five existing courses delivered in partnership. Neither does it change the fact that OBC, having had five courses forcibly de-designated, and seen the specifics of the allegations underpinning this exceptional decision put into the public domain without any meaningful rebuttal, may struggle to find willing academic partners.

The other chink of legal light came with an argument that a contract (or subcontract) could be deemed a “possession” under certain circumstances, and that article one section one of the European Convention on Human Rights permits the free enjoyment of possessions. The judgement admits that there could be grounds for debate here, but that debate has not yet happened.

Rules

Whatever your feelings about OBC, or franchising in general, the way in which DfE appears to have used a carefully redacted and summarised report to remove an institution from the sector is concerning. If the rules of the market permit behaviour that ministers do not like, then these rules need to be re-written. DfE can’t just regulate based on what it thinks the rules should be.

The college issued a statement on 25 August, three days after the judgement was published – it claims to be engaging with “partner institutions” (named as Buckinghamshire New University, University of West London, Ravensbourne University London, and New College Durham – though all four had already ended their partnerships with the remaining students being “taught out”) about the future of the students affected by the designation decision – many had already transferred to other courses at other providers.

In fact, the judgement tells us that of 5,000 students registered at OBC on 17 April 2025, around 4,700 had either withdrawn or transferred out of OBC to be taught out. We also learn that 1,500 new students, who had planned to start an OBC-delivered course after 2025, would no longer be doing so. Four lead providers had given notice to terminate franchise agreements between April 2024 and May of 2025. Franchise discussions with another provider – Southampton Solent University – underway shortly before the decision to de-designate, had ended.

OBC currently offers one course itself (no partnership offers are listed) – a foundation programme covering academic skills and English language including specialisms in law, engineering, and business – which is designed to prepare students for the first year of an undergraduate degree course. It is not clear what award this course leads to, or how it is regulated. It is also expensive – a 6 month version (requiring IELTS 5.5 or above) costs an eyewatering £17,500. And there is no information as to how students might enroll on this course.

OBC’s statement about the court case indicates that it “rigorously adheres to all regulatory requirements”, but it is not clear which (if any) regulator has jurisdiction over the one course it currently advertises.

If there are concerns about the quality of teaching, or about academic standards, in any provider in receipt of public funds they clearly need to be addressed – and this is as true for Oxford Business College as it is for the University of Oxford. This should start with a clear plan for quality assurance (ideally one that reflects the current concerns of students) and a watertight process that can be used both to drive compliance and take action against those who don’t measure up. Ministerial legal innovation, it seems, doesn’t quite cut it.