This story was reported by and originally published by APM Reports in connection with its podcast Sold a Story: How Teach Kids to Read Went So Wrong.

When voters elected Donald Trump in November, most people who worked at the U.S. Department of Education weren’t scared for their jobs. They had been through a Trump presidency before, and they hadn’t seen big changes in their department then. They saw their work as essential, mandated by law, nonpartisan and, as a result, insulated from politics.

Then, in early February, the Department of Government Efficiency showed up. Led at the time by billionaire CEO Elon Musk, and known by the cheeky acronym DOGE, it gutted the Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences, posting on X that the effort would ferret out “waste, fraud and abuse.”

A post from the Department of Government Efficiency.

When it was done, DOGE had cut approximately $900 million in research contracts and more than 90 percent of the institute’s workforce had been laid off. (The current value of the contracts was closer to $820 million, data compiled by APM Reports shows, and the actual savings to the government was substantially less, because in some cases large amounts of money had been spent already.)

Among staff cast aside were those who worked on the National Assessment of Educational Progress — also known as the Nation’s Report Card — which is one of the few federal education initiatives the Trump administration says it sees as valuable and wants to preserve.

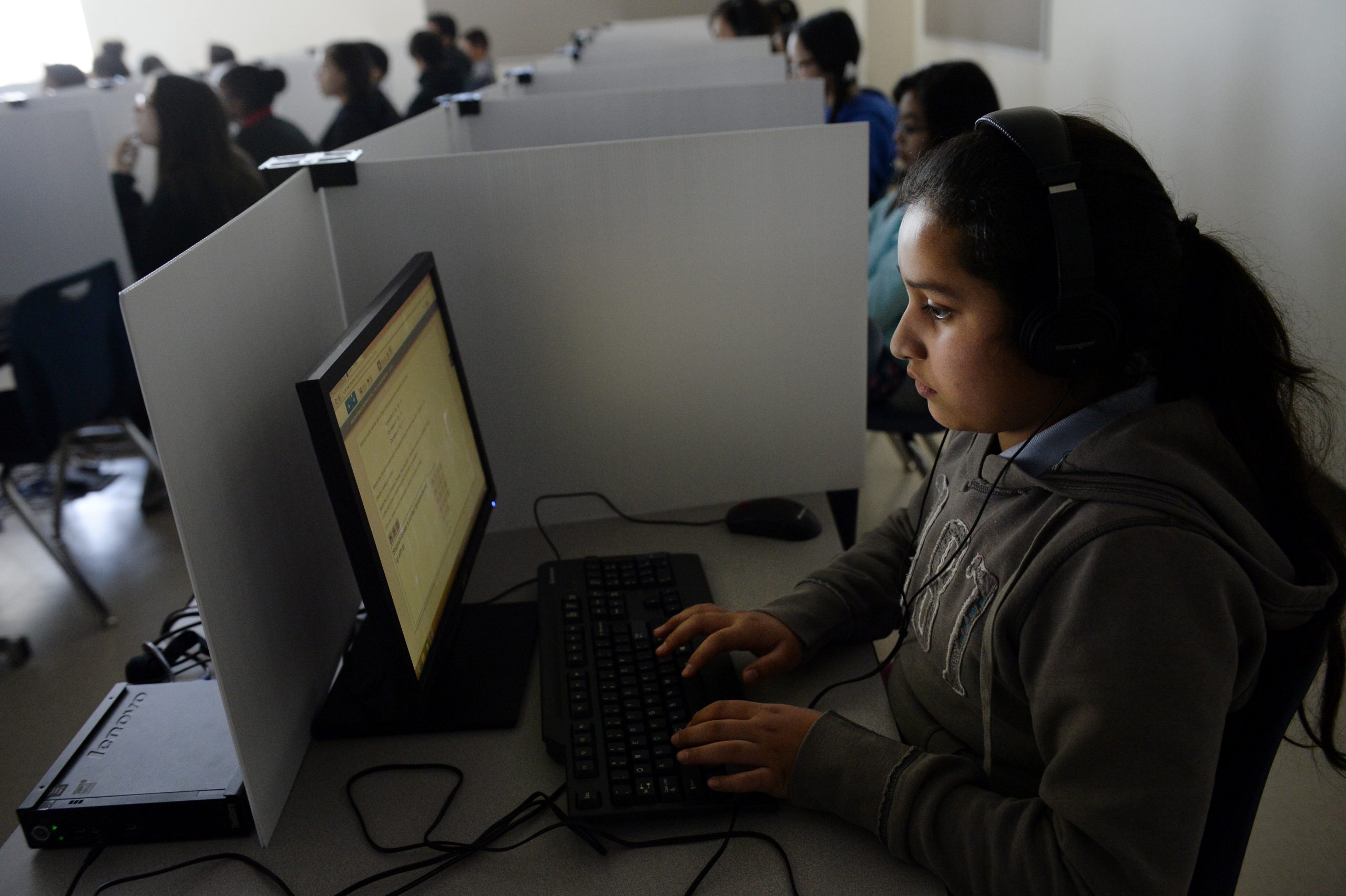

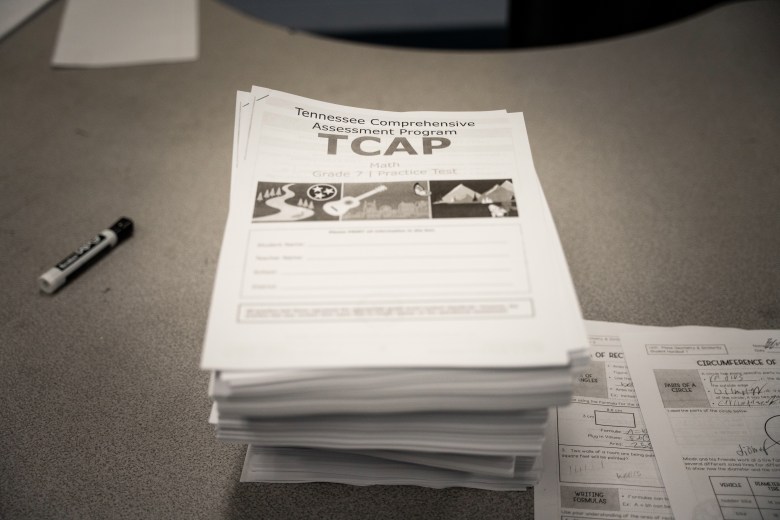

The assessment is a series of tests administered nearly every year to a national sample of more than 10,000 students in grades 4, 8 and 12. The tests regularly measure what students across the country know in reading, math and other subjects. They allow the government to track how well America’s students are learning overall. Researchers can also combine the national data with the results of tests administered by states to draw comparisons between schools and districts in different states.

The assessment is “something we absolutely need to keep,” Education Secretary Linda McMahon said at an education and technology summit in San Diego earlier this year. “If we don’t, states can be a little manipulative with their own results and their own testing. I think it’s a way that we keep everybody honest.”

But researchers and former Department of Education employees say they worry that the test will become less and less reliable over time, because the deep cuts will cause its quality to slip — and some already see signs of trouble.

“The main indication is that there just aren’t the staff,” said Sean Reardon, a Stanford University professor who uses the testing data to research gaps in learning between students of different income levels.

All but one of the experts who make sure the questions in the assessment are fair and accurate — called psychometricians — have been laid off from the National Center for Education Statistics. These specialists play a key role in updating the test and making sure it accurately measures what students know.

“These are extremely sophisticated test assessments that required a team of researchers to make them as good as they are,” said Mark Seidenberg, a researcher known for his significant contributions to the science of reading. Seidenberg added that “a half-baked” assessment would undermine public confidence in the results, which he described as “essentially another way of killing” the assessment.

The Department of Education defended its management of the assessment in an email: “Every member of the team is working toward the same goal of maintaining NAEP’s gold-standard status,” it read in part.

The National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policies for the national test, said in a statement that it had temporarily assigned “five staff members who have appropriate technical expertise (in psychometrics, assessment operations, and statistics) and federal contract management experience” to work at the National Center for Education Statistics. No one from DOGE responded to a request for comment.

Harvard education professor Andrew Ho, a former member of the governing board, said the remaining staff are capable, but he’s concerned that there aren’t enough of them to prevent errors.

“In order to put a good product up, you need a certain number of person-hours, and a certain amount of continuity and experience doing exactly this kind of job, and that’s what we lost,” Ho said.

The Trump administration has already delayed the release of some testing data following the cutbacks. The Department of Education had previously planned to announce the results of the tests for 8th grade science, 12th grade math and 12th grade reading this summer; now that won’t happen until September. The board voted earlier this year to eliminate more than a dozen tests over the next seven years, including fourth grade science in 2028 and U.S. history for 12th graders in 2030. The governing board has also asked Congress to postpone the 2028 tests to 2029, citing a desire to avoid releasing test results in an election year.

“Today’s actions reflect what assessments the Governing Board believes are most valuable to stakeholders and can be best assessed by NAEP at this time, given the imperative for cost efficiencies,” board chair and former North Carolina Gov. Bev Perdue said earlier this year in a press release.

Recent estimates peg the annual cost to keep the national assessment running at about $190 million per year, a fraction of the department’s 2025 budget of approximately $195 billion.

Adam Gamoran, president of the William T. Grant Foundation, said multiple contracts with private firms — overseen by Department of Education staff with “substantial expertise” — are the backbone of the national test.

“You need a staff,” said Gamoran, who was nominated last year to lead the Institute of Education Sciences. He was never confirmed by the Senate. “The fact that NCES now only has three employees indicates that they can’t possibly implement NAEP at a high level of quality, because they lack the in-house expertise to oversee that work. So that is deeply troubling.”

The cutbacks were widespread — and far outside of what most former employees had expected under the new administration.

“I don’t think any of us imagined this in our worst nightmares,” said a former Education Department employee, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation by the Trump administration. “We weren’t concerned about the utter destruction of this national resource of data.”

“At what point does it break?” the former employee asked.

Related: Suddenly sacked

Every state has its own test for reading, math and other subjects. But state tests vary in difficulty and content, which makes it tricky to compare results in Minnesota to Mississippi or Montana.

“They’re totally different tests with different scales,” Reardon said. “So NAEP is the Rosetta stone that lets them all be connected.”

Reardon and his team at Stanford used statistical techniques to combine the federal assessment results with state test scores and other data sets to create the Educational Opportunity Project. The project, first released in 2016 and updated periodically in the years that followed, shows which schools and districts are getting the best results — especially for kids from poor families. Since the project’s release, Reardon said, the data has been downloaded 50,000 times and is used by researchers, teachers, parents, school boards and state education leaders to inform their decisions.

For instance, the U.S. military used the data to measure school quality when weighing base closures, and superintendents used it to find demographically similar but higher-performing districts to learn from, Reardon said.

If the quality of the data slips, those comparisons will be more difficult to make.

“My worry is we just have less-good information on which to base educational decisions at the district, state and school level,” Reardon said. “We would be in the position of trying to improve the education system with no information. Sort of like, ‘Well, let’s hope this works. We won’t know, but it sounds like a good idea.’”

Seidenberg, the reading researcher, said the national assessment “provided extraordinarily important, reliable information about how we’re doing in terms of teaching kids to read and how literacy is faring in the culture at large.”

Producing a test without keeping the quality up, Seidenberg said, “would be almost as bad as not collecting the data at all.”