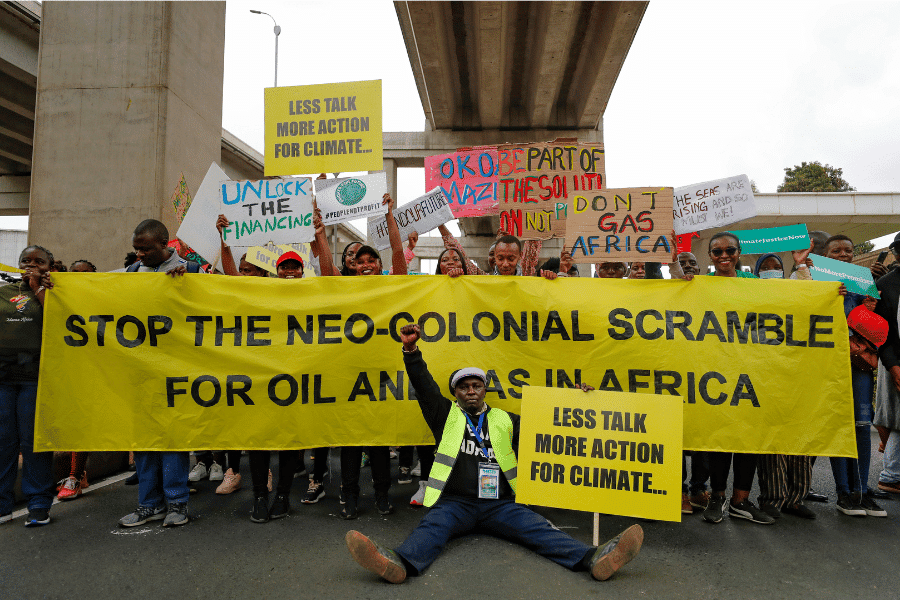

In the sticky heat of an April afternoon in Kampala, Uganda nine university students stood outside the headquarters of Stanbic Bank, their voices raised in protest. It is a sound that has echoed for more than half a decade.

Their signs called for an end to the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), a $5 billion project: 1,443 kilometers of 24-inch wide, heated and buried steel ambition, snaking from Uganda’s oil-rich Lake Albert basin to the Tanzanian port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean. Before the hour was out, they were in police custody.

The government has hailed the project as a pillar of economic transformation. But critics — students, activists, and environmental groups — argue it will displace communities, threaten biodiversity and entrench a model of development that sidelines democratic participation. Dissent has been met with arrests, surveillance and a steadily shrinking civic space. The protests, though often silenced, persist, challenging a narrative that equates oil with progress.

Five days after the arrests, in the same city, a different kind of statement was made. At the Eleventh Africa Regional Forum on Sustainable Development, held from April 7th to 11th, delegates issued a call that seemed — if only for a moment — to resonate with those voices on the street.

The route of the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline. Wikimedia Commons

Members of the UN Economic Commission for Africa urged a shift away from exporting raw materials and toward value addition through manufacturing and industrialisation. Mining, they said, and the export of cash crops like cocoa, tea and coffee must no longer be the end of the story, but the beginning of something built to last.

Shouting into the void

For the students arrested, whose protests have long been dismissed as anti-developmental by a government intent on progress-by-pipeline, this sudden harmony of rhetoric might feel like vindication — if only the delegates meant what they propose.

The students may have been shouting into a void, but the echoes resonate with a wider pattern etched deep into the continent’s political and economic architecture. Back in 2016, journalist Tom Burgis, author of “The Looting Machine”, put it in a 2016 interview with CNN: “There is a pretty straight line from colonial exploitation to modern exploitation.”

Burgis has long documented the mechanisms of resource extraction in Africa and pointed to the lingering dominance of oil and mining multinationals — entities that, decades after independence, still wield economic and political influence akin to that once held by colonial administrations.

Zaki Mamdoo, a South African climate justice activist and campaigner with the Stop EACOP coalition, agrees with Burgis’s notion of modern resource imperialism — only now, the governors wear suits and operate through shareholder meetings.

“How come TotalEnergies owns 62% shareholding power, while Uganda and Tanzania hold just 15% each?” he said.

Partnership or plunder?

The numbers speak for themselves. The French oil giant TotalEnergies, with Chinese partner CNOOC in tow, controls the lion’s share of the project. Uganda, the country from which the oil originates, has been cast in the role of host, not owner. Tanzania, whose land will bear the pipeline’s longest stretch, fares no better. For Mamdoo and many others, this is not a partnership; it’s a palatable version of plunder.

“This is not African-led development,” Mamdoo said. “It’s an extractive model dressed up in nationalist rhetoric.”

To critics, EACOP is a 21st-century replay of old patterns — resources extracted with little local benefit, profits flowing abroad and environmental costs left with the people. What’s different now is the packaging: marketed as part of an energy transition and a driver of economic empowerment. But on the ground, the reality is displacement, disrupted livelihoods and fragile ecosystems in the pipeline’s path.

According to EACOP’s official figures, more than 13,600 people have been affected, with 99.4% of compensation agreements signed and paid. But activists argue the numbers mask deeper issues — slow and uneven compensation, uprooted communities and long-term uncertainty.

“The real number is far higher,” said Mamdoo. “We’re talking well over 100,000 directly impacted — and many more indirectly. But of course, Total reports a few tens of thousands.”

Differing views on sustainability

From Uganda’s farmlands to Tanzania’s reserves, the pipeline cuts through forests, wetlands and biodiversity hotspots — what critics see as a trail of ecological and human disruption beneath a polished PR campaign.

By underreporting those impacted, critics argue, multinationals shrink their obligations — and their compensation budgets. The payments, when they come, have been slow, sporadic and, in some cases, still absent. Yet the construction rolls forward.

To Morris Nyombi, a Ugandan activist now living in exile for his work opposing EACOP, the narrative of compensation is as hollow as it is dangerous.

He watches from afar as national television and international media spotlight a few smiling beneficiaries — residents celebrating a new house, a fresh coat of paint, a sense of reward.

Nyombi sees what isn’t shown. “Let’s state facts, when minerals are found somewhere, just know that’s lost land — it becomes government property,” Nyombi said. “And to the select few given houses, what then? You’re an agriculturist. Giving you a house somewhere else doesn’t mean giving you land to till. You’re killing a way of life.”

A pipeline of displacement

Without farmland, families are forced to sell off whatever land remains and move to towns and cities in search of new beginnings.

“They end up in Kampala renting, looking for what to do,” Nyombi said. “It’s displacement without a plan. Progress for someone else.”

Farmers who were near the pipeline’s path are now scattered across the Uganda-Congo border, Nyombi said. “They were duped into compensation. When they resisted, they started receiving threats. Husbands arrested. The women and children forced to run, to hide. That’s the reality.”

These, Nyombi said, are the people the government never talks about. They don’t show up in speeches or glossy brochures about development. But their lives tell the story better than any pipeline prospectus ever could.

But speaking out against EACOP is dangerous. “It’s a gamble with one’s life,” Nyombi said. Being an activist, he adds, is a kind of social exile. Most organizations won’t hire you — won’t even stand next to you. In much of Africa, governments don’t hesitate to hit below the belt.

A lake that sustains life

Nyombi has been on the government’s radar since 2020. He has been threatened and surveilled and been the subject of smear campaigns. As a result, he stepped back from frontline organizing.

But what if the project were perfectly managed with strict environmental safeguards, zero corruption and full compensation? Would that make EACOP justifiable?

Mamdoo said that isn’t what is happening, citing reports of oil slicks on Lake Albert and elephants rampaging villages. The very question betrays a fundamental misunderstanding, Mamdoo said. Environmental damage isn’t a hypothetical risk, it’s already unfolding.

“If oil spills hit Lake Victoria—the region’s largest freshwater body—over 40 million people would be poisoned,” he said.

Lake Victoria sustains agriculture, fishing, drinking water, and transport across Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. It’s East Africa’s largest inland water body — and the source of the Nile. Yet while project backers point to EACOP’s technical safeguards, critics like Mamdoo argue that no pipeline cutting through seismically active zones, protected ecosystems and critical watersheds can ever be truly safe.

“You can’t just contain a pipeline,” Mamdoo adds. “You can’t plug all the holes when the system is built to leak — money, justice, land, people.”

Keeping oil where it is extracted

Supporters of the pipeline argue that projects like EACOP could open the door for substantial donations to tourism development and wildlife protection, especially in ecologically sensitive zones where the pipeline runs near or through national parks. The idea is that the extractive industry might fund preservation as part of its footprint.

But to Mamdoo, that premise is flawed from the start.

“What’s that compared to the 62% they’re taking?” Mamdoo asks. “You shouldn’t settle for peanuts when you own a resource.”

Being a funder, he adds, doesn’t make you the owner. Mamdoo would like to see the oil stay in Uganda. “We’d be having an entirely different conversation if the plan was to have our own refineries, process it locally, then sell the products to them,” he said.

Nyombi isn’t surprised that the government supports EACOP. Historically, leaders who stand up to corporations and the Global North haven’t lasted. “These multinationals don’t want an Africa that sees clearly,” Nyombi continues. “They want us manageable. If you open your eyes and demand real sovereignty, you become a threat to global stability.”

Taking on global establishment isn’t easy.

Some critics point to the case of Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader who championed a gold-backed African currency and pan-African resource control before being toppled in a NATO-backed intervention. His fall, they argue, wasn’t just about domestic tyranny — it was about challenging the global status quo.

Yet among younger Ugandans, particularly students, the legacy of figures like Gaddafi is often blurred or reduced to villainy — taught more as a cautionary tale than a case study in resistance. The narratives they inherit are tightly curated. But still, a shift is happening.

Especially among those studying environmental science, Nyombi sees a growing restlessness.

“These students, they want to act,” Nyombi said. “They’re interested in ground action. But more than that — they’re asking deeper questions. They wonder, why keep planting trees that won’t grow?”

There’s a frustration with symbolic gestures — school-organized clean-ups, ceremonial tree-plantings — that often sidestep the policies creating the very destruction they’re meant to remedy.

“They’re starting to say, no, the problem isn’t the seedling. It’s the system. So why not challenge policy instead?” Nyombi said. “But to challenge policy, you have to get out there.”

That’s how the students who were arrested on 2 April while approaching Uganda’s Stanbic Bank came to act.

Taking protests to the front line

Mamdoo said that the protest was not just symbolic — it was strategic. Stanbic is one of the banks linked to funding the East African Crude Oil Pipeline. For the students, it was the front line.

“They’re trying to secure their future,” Mamdoo said.

But the bank saw it differently. Kenneth Agutamba, Stanbic Uganda’s country manager for corporate communications, defended the institution’s involvement.

“Our participation aligns with our commitment to a just transition that balances economic development with environmental sustainability,” Agutamba said. “The project has met all necessary compliance requirements under the Equator Principles and our Climate Policy.”

For the students, though, no statement or principle outweighs what they see as the theft of their future. Their protest, they insist, is not rooted in mere outrage. It’s anchored in a growing global reckoning: at least 43 banks and 29 insurance companies have declined to support EACOP, citing its environmental threats and human rights risks.

But despite the pressure from abroad, the pipeline — and the crackdowns — continue to move forward.

“That’s why we’re targeting the funders,” Mamdoo said. “If the money dries up, the project can’t survive.”

Dissent and disappearance

The students arrested will likely be released — this time. They’re lucky. Local papers spoke of them. Many others vanish into cells for months, even years, without trial — especially those without lawyers, or whose names never make it into the headlines.

If there’s a single line that captures the price of resistance, it might be Braczkowski’s blunt warning: “Any oil activist in Uganda will be sniffed out before Total.” Oil, he adds, has become Uganda’s gold — a lifeline that may help service the country’s mounting debt.

“That’s exactly the problem,” Mamdoo counters. “If all it does is pay off debt, what’s left for the people? There won’t be money for schools, for hospitals — just enough to keep the lights on in their offices.”

It’s been nearly a decade since EACOP was first proposed. Only now, as shovels hit soil and risks become real, has public scrutiny begun to catch up. And that, Mamdoo and Nyombi agree, is because of activism.

“Without it,” Nyombi said, “this would’ve gone quietly. Smoothly. Just another deal signed behind closed doors.”

But things aren’t moving as fast as they once were.

“Activism has slowed them down,” Nyombi adds. “It’s not moving at the pace they wanted.”

So what’s the real equation here? A pipeline backed by billions. A government banking on oil. A continent still clawing for control of its wealth. And in the middle — students, farmers, mothers, exiles — bearing the cost of asking the most dangerous question of all:

What if we said no?

Three questions to consider:

1. What is EACOP?

2. Why are many people in East Africa opposed to a pipeline that promises to bring money to the region?

3. If you were in charge of natural resources for Uganda, what policies would you put in place?